POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

BY MARK MATHER, LINDA A. JACOBSEN, AND KELVIN M. POLLARD

AGING IN THE

UNITED STATES

Population Bulletin

www.prb.org

DECEMBER 2015

VOL. 70, NO. 2

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

The Population Reference Bureau INFORMS people around

the world about population, health, and the environment,

and

EMPOWERS them to use that information to ADVANCE

the well-being of current and future generations.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Stanley Smith, Chair of the Board

Professor Emeritus and Population Program Director,

Bureau of Economic and Business Research,

University of Florida, Gainesville, Fla.

Elizabeth Schoenecker, Vice Chair of the Board

Former Chief, Policy, Evaluation, and Communication Division, Oce

of Population and Reproductive Health, USAID, Washington, D.C.

Susan E. McGregor, Secretary of the Board

Assistant Professor, Journalism and Assistant Director, Tow Center

of Digital Journalism, Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

Richard F. Hokenson, Treasurer of the Board

Senior Managing Director and Partner, Evercore ISI, New York, N.Y.

Jeffrey Jordan, PRB President and Chief Executive Officer

Population Reference Bureau, Washington, D.C.

Christine A. Bachrach, Research Professor, Department of

Sociology and Maryland Population Research Center,

University of Maryland, College Park, Md.

Alaka Basu, Professor, Development Sociology, Cornell University,

Ithaca, N.Y.

Bert T. Edwards, Retired Partner, Arthur Andersen LLP and former

Assistant Secretary/CFO, U.S. State Department, Washington, D.C.

Parfait M. Eloundou-Enyegue, Professor, Development,

Sociology, and Demography and Associate Director,

Cornell Population Program, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

David Finn, Executive Director and Associate General Counsel,

Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit, Seattle, Wash.

Amanda Glassman, Director, Global Health Policy and Senior

Fellow, Center for Global Development, Washington, D.C.

Robert M. Groves, Provost and Gerard Campbell Professor,

Department of Mathematics and Statistics and Department of

Sociology, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Jamie Herring, Founder and President, HabitatSeven,

Ottawa, Canada

Scott C. McDonald, President, Nomos Research,

New York, N.Y.

Marta Tienda, Maurice P. During ’22 Professor, Demographic

Studies and Sociology and Public Aairs, Princeton University,

Princeton, N.J.

Linda J. Waite, Lucy Flower Professor, Urban Sociology,

University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

Carolyn L. West, Senior Vice President, Public Finance,

PNC Bank N.A., Washington, D.C.

The Population Bulletin is published twice a year and distributed to

members of the Population Reference Bureau. Population Bulletins are

also available for $7 each (discounts for bulk orders). To become a PRB

member or to order PRB materials, contact PRB, 1875 Connecticut Ave.,

NW, Suite 520, Washington, DC 20009-5728; Tel.: 800-877-9881;

Fax: 202-328-3937; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.prb.org.

The suggested citation, if you quote from this publication, is:

Mark Mather, Linda A. Jacobsen, and Kelvin M. Pollard, “Aging in the

United States,” Population Bulletin 70, no. 2 (2015). For permission to

reproduce portions from the Population Bulletin, write to PRB: Attn:

Permissions; or e-mail: [email protected].

Cover photo: iStock.com/Squaredpixels.

© 2015 Population Reference Bureau. All rights reserved.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

MARK MATHER is associate vice president in U.S. Programs at the

Population Reference Bureau. LINDA A. JACOBSEN is vice president

in U.S. Programs at PRB. KELVIN M. POLLARD is senior demographer

in U.S. Programs at PRB.

Funding for this Population Bulletin was provided through the

generosity of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

AGING IN THE UNITED STATES

BY MARK MATHER, LINDA A. JACOBSEN,

AND KELVIN M. POLLARD

DECEMBER 2015

VOL. 70, NO. 2

POPULATION REFERENCE BUREAU

Population Bulletin

INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................2

DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS ...........................................................................2

Figure 1. The Number of Americans Ages 65 and Older Will More

Than Double by 2060 .....................................................................................

3

Figure 2. By 2060, Nearly One-Quarter of Americans Will Be Ages

65 and Older ..................................................................................................

3

Figure 3. Despite Growing Diversity, Non-Hispanic Whites Will

Account for More Than Half of Older Americans Through 2060 ........................

4

Figure 4. The Current “Diversity Gap” Between the 60+ Population and

Younger Generations Will Widen by 2030. .......................................................

4

MARITAL STATUS AND LIVING ARRANGEMENTS ....................................4

Figure 5. The Share of Divorced Americans Ages 65 and Older

Is Increasing, While the Proportion Widowed Is Declining ................................

5

Box 1. Defining Housing Units and Group Quarters .......................................6

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT .....................................................................6

Figure 6. More U.S. Men Than Women Ages 65 and Older Have

Bachelor’s Degrees ........................................................................................

6

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION .................................................................... 6

Figure 7. Older Americans Make Up At Least 20 Percent of the

Population in One-Quarter of U.S. Counties ....................................................

7

ECONOMIC SECURITY ...............................................................................7

Figure 8. As Social Security Benefits Have Expanded, the Poverty

Rate Among Americans Ages 65 and Older Has Declined ...............................

8

Figure 9. Social Security Is the Primary Income Source for Older

Americans With Low Incomes.........................................................................

9

Box 2. Effect of the Great Recession on Older Adults ..................................10

Figure 10. The Share of U.S. Men and Women Ages 65 and Older

in the Labor Force Has Grown Since the 1990s ............................................

11

Figure 11. College-Educated Americans Are More Likely to Be in

the Labor Force After Age 65. .......................................................................

11

HEALTH AND WELL-BEING ......................................................................11

Figure 12. Obesity Continues to Increase Among Older Americans. ...........12

Box 3. Narrowing Old-Age Gender Gap in the United States Linked to

Declines in Smoking .....................................................................................

13

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ......................................................14

Figure 13. Social Security and Medicare Expenditures Are Projected

to Reach a Combined 12 Percent of GDP by 2050. .......................................

14

Box 4. Aging Populations Challenge Countries Worldwide...........................15

Figure 14. By 2030, There Will Be Only About Three Working-Age

Adults for Every Person Age 65 or Older .......................................................

15

CONCLUSION ............................................................................................16

REFERENCES ............................................................................................17

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

2

www.prb.org

The current growth of the population ages 65 and older is one

of the most significant demographic trends in the history of

the United States. Baby boomers—those born between 1946 and

1964—have brought both challenges and opportunities to the economy,

infrastructure, and institutions as they have passed through each major

stage of life. Although U.S. policymakers and others have had many

decades to plan for the inevitable aging of the baby boom cohort, it is not

clear that sufficient preparations have been made to meet baby boomers’

anticipated needs in old age.

AGING IN THE UNITED STATES

Many older Americans rely

on family caregivers, but

high divorce rates and

fewer children among

baby boomers may reduce

the availability of family

caregivers in the future.

2.3

MILLION

The number of nursing home

residents in 2030 if the share

of Americans ages 65+ living

in nursing homes remains at

2010 levels.

4 in 10

Adults ages 65 to 74 who

were obese in 2009-2012.

Declines in both fertility

and immigration related

to the Great Recession

have accelerated the

growth in the share of

the U.S. population

ages 65 and older.

Planning for the future needs of older

adults is complicated, in part because

the baby boom generation is one of

contradictions. While some current

characteristics of baby boomers suggest

that they will experience more economic

security in old age than previous generations,

other traits will pose challenges for

policymakers and service providers.

Compared with earlier cohorts, baby

boomers have higher levels of education and

more years of work experience, which should

increase their lifetime earnings and economic

security as they reach age 65 and beyond.

However, fewer children and high divorce

rates among baby boomers mean that more

may live alone in old age without either

the financial and social support or informal

caregiving provided by a spouse or child.

Life expectancy in the United States is

increasing, and today’s older adults—

especially those ages 85 and older— have

lower rates of disability than the generations

that preceded them. But rising obesity rates

put adults ages 55 to 64 at higher risk for

chronic disability in old age, compared with

their parents’ generation.

There are also wide disparities in the

economic and physical welfare of older adults

by gender and across different racial/ethnic

groups. Older women are more likely to live

alone than men and are twice as likely to be

poor. At age 50, black men and women

still have lower life expectancies than their

white counterparts. And among adults ages

65 and older, racial/ethnic minorities are

much more likely than whites to rely solely

on Social Security for their family income.

Policymakers and others need to pay

attention to these gender and racial/ethnic

gaps, which could undermine progress in

advancing the well-being of older Americans

in the coming decades.

This Population Bulletin examines trends in

the size and characteristics of the population

ages 65 and older in the United States, and

considers the risks, costs, and implications

for the future.

Demographic Trends

SIZE AND AGE COMPOSITION

The number of people ages 65 and older

in the United States has increased steadily

since the 1960s, but is projected to more than

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

3

double from 46 million today to more than 98 million by 2060

(see Figure 1). Between 2020 and 2030 alone, the number

of older persons is projected to increase by almost 18 million

as the last of the large baby boom cohorts reaches age 65.

Although much smaller in total size, the number of people

ages 85 and older is projected to more than triple from 6

million today to nearly 20 million by 2060.

The number of centenarians, or people age 100 or older, has

also increased from around 32,000 in 1980 to more than

53,000 by 2010.

1

If life expectancy at older ages continues

to rise in the United States, then the number of centenarians

could increase to more than 600,000 by 2060, although they

would still make up less than 1 percent of the population ages

65 and older for that year.

2

While the youngest members of the baby boom generation will

not turn 65 for another 15 years, recent declines in fertility and

in immigration to the United States due to the Great Recession

have accelerated growth in the share of the population that is

ages 65 and older. In 1960, only 9 percent of the population

was age 65 or older, while more than one-third (36 percent)

was under age 18 (see Figure 2). By 2014, children made up

less than one-fourth of the total population (23 percent), while

those ages 65 and older made up 15 percent, or nearly one-

sixth of the total. In 2008, U.S. Census Bureau projections

showed the number and share of children exceeding that of

the older population every year through 2050, while more

recent projections show the number and share of the older

population surpassing that of children by 2035.

The future size of the older population, relative to the

population of children and working-age adults, will depend

in part on trends in immigration. The latest projections from

the Census Bureau assume that the net number of annual

immigrants—most of whom are working-age adults—will

peak at around 1.5 million per year by 2060. But if future

immigration levels are higher than the current Census Bureau

projections, the future size of the older population would be

reduced relative to younger age groups.

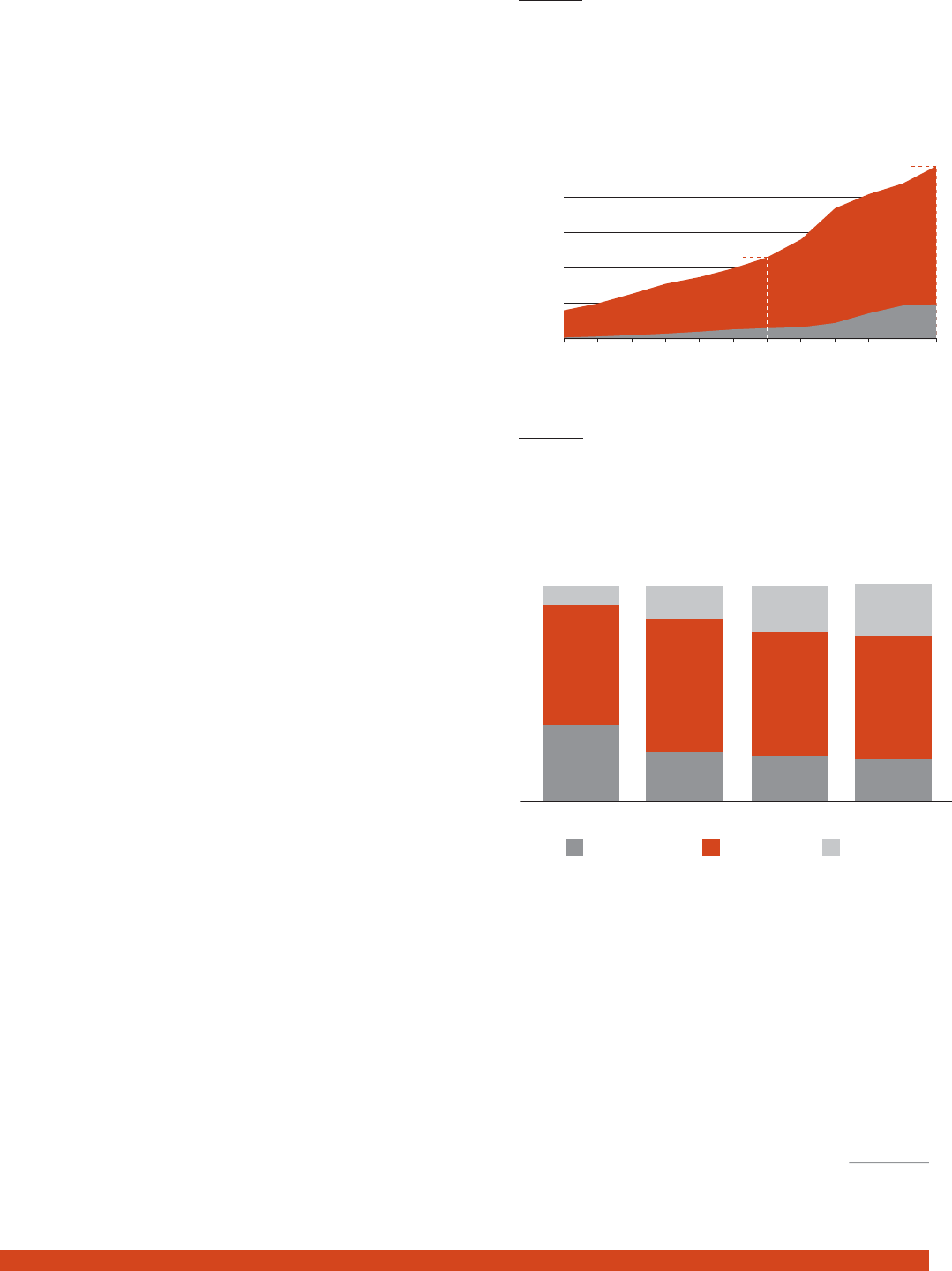

RACIAL AND ETHNIC COMPOSITION

The U.S. population is becoming more racially and ethnically

diverse, but this diversity is still concentrated in the youngest

age groups. In 2014, more than three-fourths of people ages

65 and older were non-Hispanic white compared with only

half of children under age 18. While the older population will

gradually become more diverse, more than half are projected

to remain non-Hispanic white through 2060 (see Figure 3,

page 4). However, between 2030 and 2060, the share of the

older population that is non-Hispanic white will drop by 17

percentage points, and the share that is Hispanic will double

from 11 percent to 22 percent.

The changing racial/ethnic composition of the population

under age 18, relative to those ages 65 and older, has

created a “diversity gap” between generations. In 1960,

the racial/ethnic profile was fairly similar for successive

generations (see Figure 4, page 4). That is, there was no more

than a 3 percentage-point difference in the share who were

minorities between adjacent age groups. However, by 2014,

sizeable gaps in the percent minority had emerged between

adults in their 40s and 50s and both those who were ages 20

to 39 (9 percentage points) and those who were ages 60 and

older (11 percentage points). Today, nearly half of those under

age 20 are members of a minority group compared with only

one-fourth of those age 60 or older.

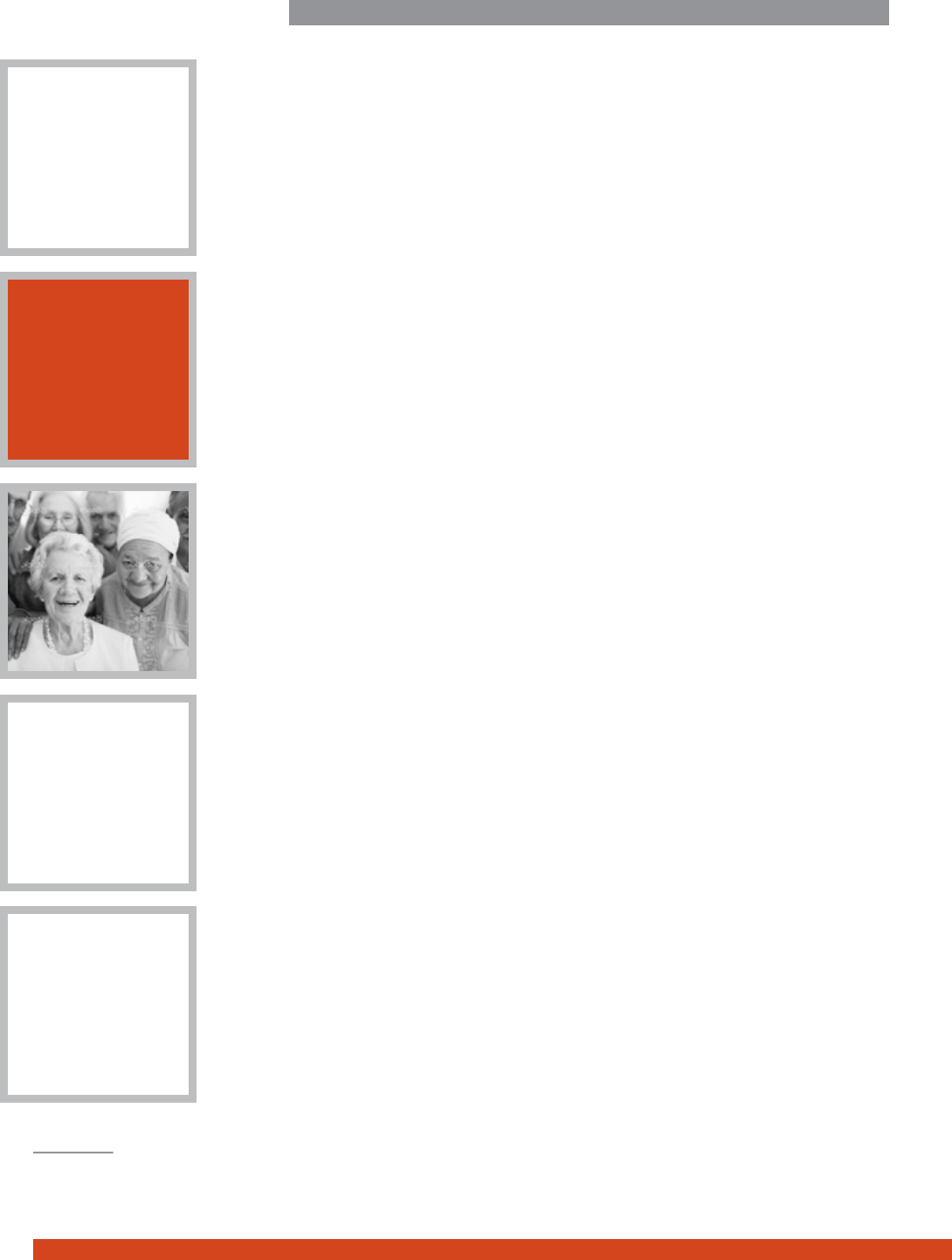

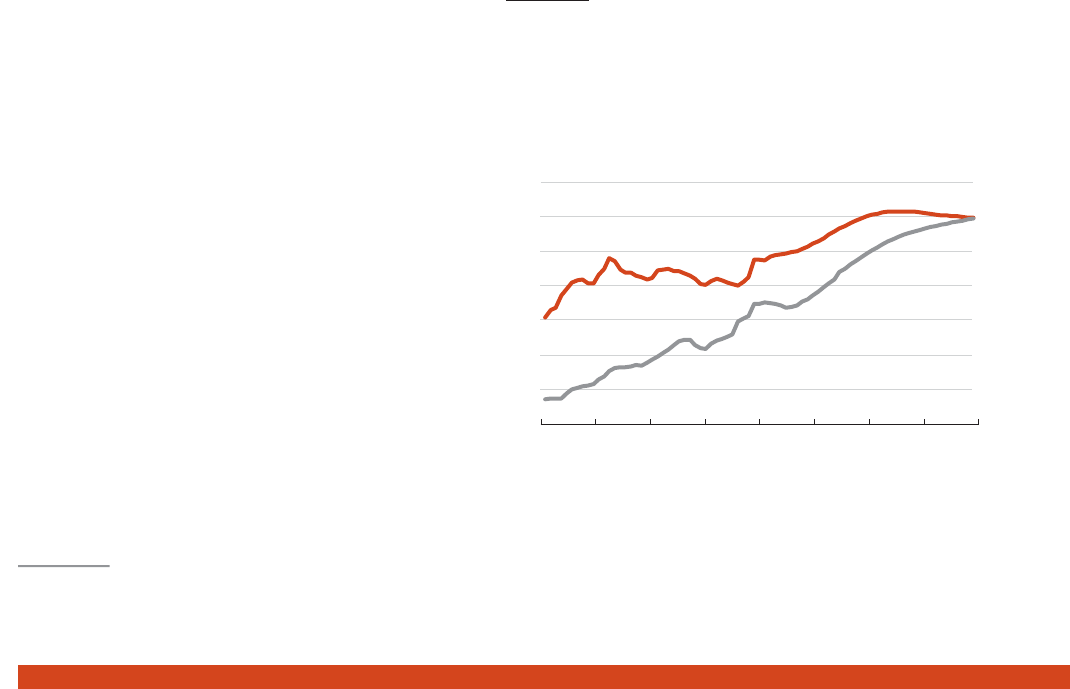

FIGURE 1

The Number of Americans Ages 65 and Older Will More

Than Double by 2060.

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060

U.S. Population Ages 65 and Older, 1960 to 2060 (Millions)

46 Million

0

20

40

60

80

100

Ages 85+

Ages 65–84

2014

98 Million

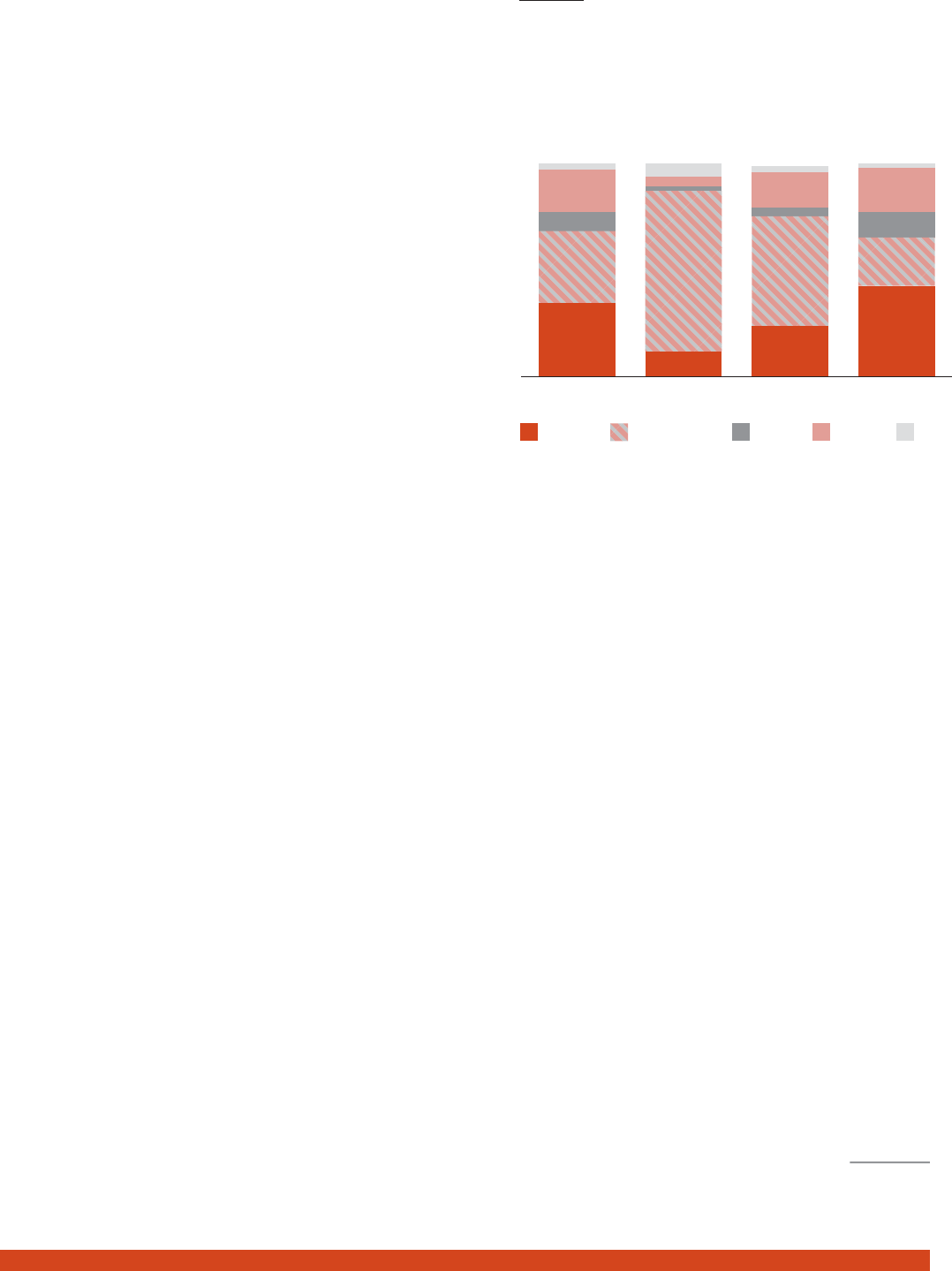

FIGURE 2

By 2060, Nearly One-Quarter of Americans Will Be Ages

65 and Older.

1960 2014 2030 2060

Under Age 18

Percent of U.S. Population in Selected Age Groups, 1960 to 2060

Ages 18-64 Ages 65+

9%

55%

36%

15%

62%

23%

21%

58%

21%

24%

57%

20%

Note:

Numbers may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

4

The generational divides between the age groups under 60

will shrink somewhat by 2030, but the gap between adults

ages 40 to 59 and those ages 60 and older will increase to 15

percentage points. When baby boomers comprise a majority

of those ages 60 and older in 2030, less than one-third

(30 percent) of this age group is projected to be members

of a minority age groups compared with more than half of

those under age 40. By 2060, nearly half of older adults are

projected to be racial/ethnic minorities—roughly the same

share as those under age 20 today.

At the societal level, the diversity gap could increase

intergenerational conflict over public resources between a

mostly white older population—eligible for Social Security

and Medicare benefits—and a younger and racially/ethnically

diverse population entering the workforce during the current

period of economic instability.

3

Marital Status and Living

Arrangements

MARITAL STATUS

Marital status and living arrangements play an important role

in social support, economic well-being, and the availability

of caregivers for those ages 65 and older. Since 1960, the

proportion of older women who are married has increased

steadily while the proportion who are widowed has declined

by 19 percentage points primarily due to rising life expectancy

among men (see Figure 5, page 5). However, despite these

positive trends for women, a sizeable gender gap remains—

nearly three-fourths of men ages 65 and older are married

compared with only half of older women. Older men are also

much less likely to be widowed than older women for two

reasons: Women’s higher life expectancy means more wives

outlive their husbands and widowed men are more likely than

women to remarry. Most adults in the United States still marry

at least once—since 1960, less than 10 percent of older men

and women have never been married. But the rise in divorce

rates beginning in the 1960s has resulted in increasing shares

of older adults who are divorced.

These marital status trends may shift by 2030 when the large

baby boom cohort dominates the population ages 65 and

older. As young adults, baby boomers were influenced by the

dramatic changes in marriage and family formation that began

during the late 1960s and continued into the early 1980s.

Marriage and childbearing were delayed until older ages,

divorce rates rose sharply, and cohabitation and nonmarital

childbearing became more common. As a result, the marital

status of baby boomers at older ages may be quite different

from that of preceding generations. For example, by ages

45 to 63 a higher share of baby boomers (34 percent) were

unmarried than the previous generation, and baby boomers

who were unmarried were less likely to be widowed and more

likely to be never-married or divorced than earlier cohorts.

4

In fact, recent data indicate a slight increase in divorce rates,

particularly among those over age 50 in what is being termed,

1960

Percent Minority in United States, by Age Group, 1960, 2014, 2030 and 2060

2014

Year

2060

Under Age 20

Ages 40-59

18%

15%

12%

9%

48%

43%

34%

53%

23%

51%

45%

30%

Ages 20-39

Ages 60+

64%

61%

57%

47%

2030

Note:

Minorities include all racial and ethnic groups except non-Hispanic whites.

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau; and IPUMS USA, University of

Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

FIGURE 4

The Current “Diversity Gap” Between the 60+ Population

and Younger Generations Will Widen by 2030.

2014

White Alone

Percent Distribution of Population Ages 65 and Older by Race/Ethnicity,

2014, 2030, and 206

0

Black Alone Hispanic/Latino

Asian Alone Other

20602030

1%

4%

8%

9%

78%

2%

5%

11%

10%

72%

3%

9%

22%

12%

55%

FIGURE 3

Despite Growing Diversity, Non-Hispanic Whites

Will Account for More Than Half of Older Americans

Through 2060.

Note:

Racial groups exclude persons of Hispanic origin. “Other” includes American

Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Other Pacifi c Islanders, and people

who identify with more than one race. Numbers may not sum to 100 due to rounding

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

5

“a gray divorce revolution.”

5

The increase in the share of

unmarried baby boomers has also been associated with a rise

in cohabitation.

6

About 9 percent of unmarried baby boomers

ages 45 to 63 were cohabiting in 2009.

7

LIVING ARRANGEMENTS

The vast majority of older adults in the United States

live in housing units such as homes and apartments (96

percent), rather than in group quarters such as nursing

homes (4 percent).

8

But the wide variety of housing options

designed specifically for seniors can make this distinction

confusing (see Box 1, page 6). Among those ages 65 and

older who resided in group quarters in 2010, most men

(80 percent) and women (89 percent) were in nursing or

skilled-nursing facilities, with an additional 6 percent of men

in correctional facilities. For the remaining group quarters

residents, 13 percent of men and 10 percent of women

lived in noninstitutional settings such as group homes,

residential treatment centers, religious group quarters (such

as monasteries), or emergency shelters. Of course, the

proportion of older adults living in nursing homes increases

considerably as they reach ages 80 and beyond. While just

7 percent of women ages 80 to 89 lived in nursing homes in

2010, this share almost tripled (19 percent) for those ages

90 to 99 years and jumped to 35 percent for those ages 100

and older.

9

Even if the shares of older men and women living

in nursing or skilled-nursing facilities in the future remain

constant at 2010 levels, the larger number of baby boomers

will mean substantial increases in the number of people

needing such living arrangements after 2030. For example,

while 1.3 million people ages 65 and older lived in nursing or

skilled-nursing facilities in 2010, this number would rise to 2.3

million by 2030 and nearly 3 million by 2060.

The differences in marital status among older men and

women are also reflected in the living arrangements of those

who live in households. Older women are much less likely

to be married than older men and more likely to live alone.

More than one-fourth (27 percent) of women ages 65 to 74

live alone, and this share jumps to 42 percent among women

ages 75 to 84, and to 56 percent among women ages 85 and

older.

10

Even at ages 85 and older, less than one-third (30

percent) of men live alone.

Older adults who live alone lack another household member

to help them bathe, dress, cook, eat, or provide care if

they are injured or become ill. Older adults who live alone,

particularly women, also have lower levels of income and

are more likely to live in poverty. If a higher share of baby

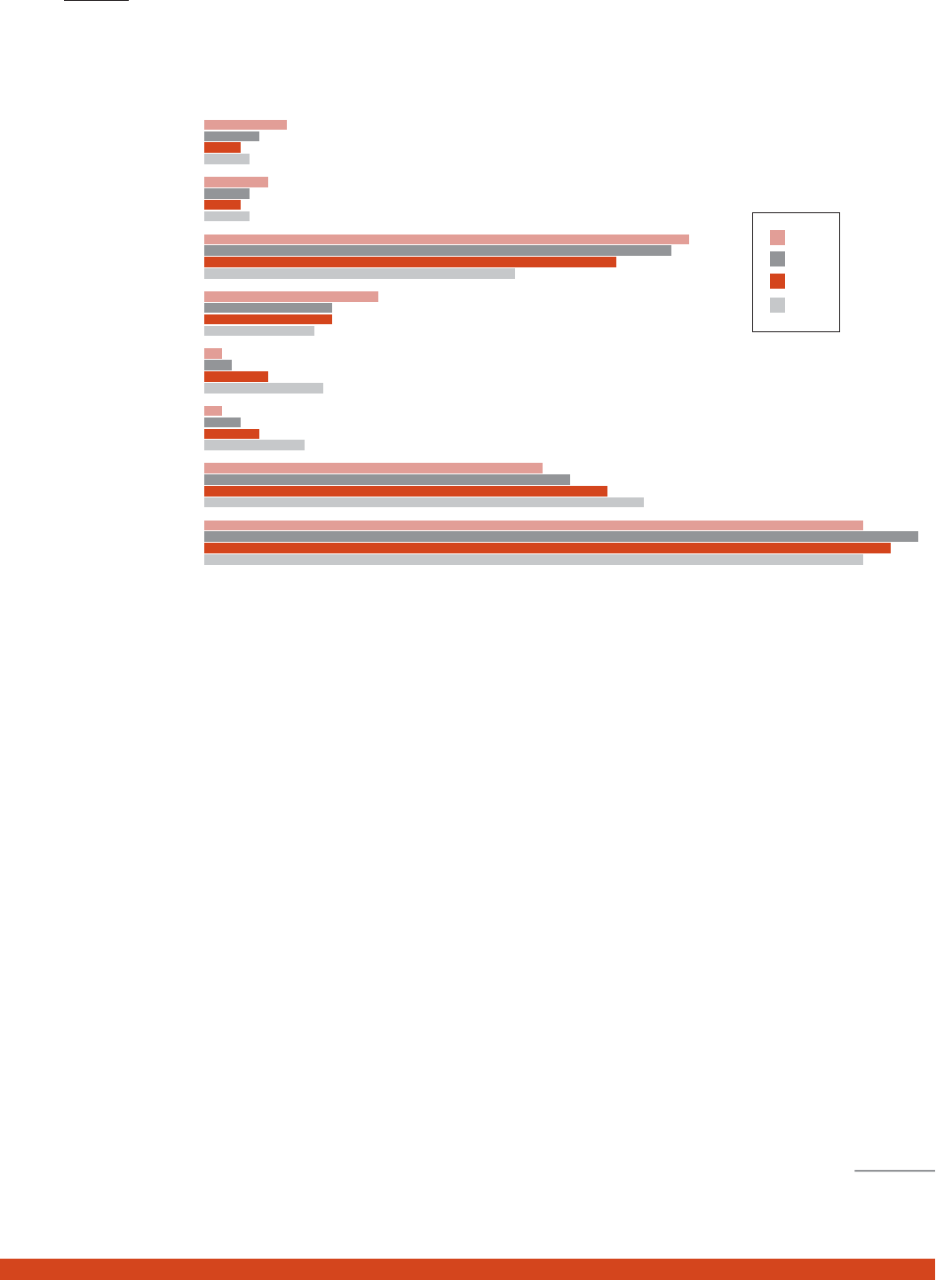

FIGURE 5

The Share of Divorced Americans Ages 65 and Older Is Increasing, While the Proportion Widowed Is Declining.

1960

1980

2000

2015

Never Married

Women

Never Married

Men

Widowed

Women

Widowed

Men

Divorced

Women

Divorced

Men

Married

Women

Married

Men

Marital Status of Persons Ages 65 and Older by Age and Sex, 1960, 1980, 2000, and 2015 (Percent)

9%

6%

4%

5%

7%

5%

4%

5%

53%

51%

45%

34%

19%

14%

14%

12%

2%

3%

7%

13%

2%

4%

6%

11%

37%

40%

44%

48%

72%

78%

75%

72%

Note:

Married includes married spouse present, married spouse absent, and separated.

Source:

U.S. Census Bureau, 1960 Census, 1980 Census, 2000 Census, and PRB analysis of data from the 2015 Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

6

Educational Attainment

Education levels have been rising steadily since the mid-

1960s, resulting in a higher share of older adults who have

completed high school and college. Completing education

beyond high school is associated with longer life expectancy

and better health at older ages.

13

Among people ages 65 and

older in 1965, only 5 percent had completed a bachelor’s

degree or more.

14

By 2014, this share had risen to 25 percent.

However, the gender differences in college attendance

and completion among young adults before the 1970s are

reflected in the educational distribution of older adults today.

While about one-fourth of both men and women ages 65 and

older have completed some college, 31 percent of older men

have completed a bachelor’s degree or more, compared with

only 20 percent of older women (see Figure 6). Lower levels

of education among older women are important because they

are tied to lower income levels and higher poverty rates.

Geographic Distribution

Today, about 15 percent of the U.S. population is ages 65

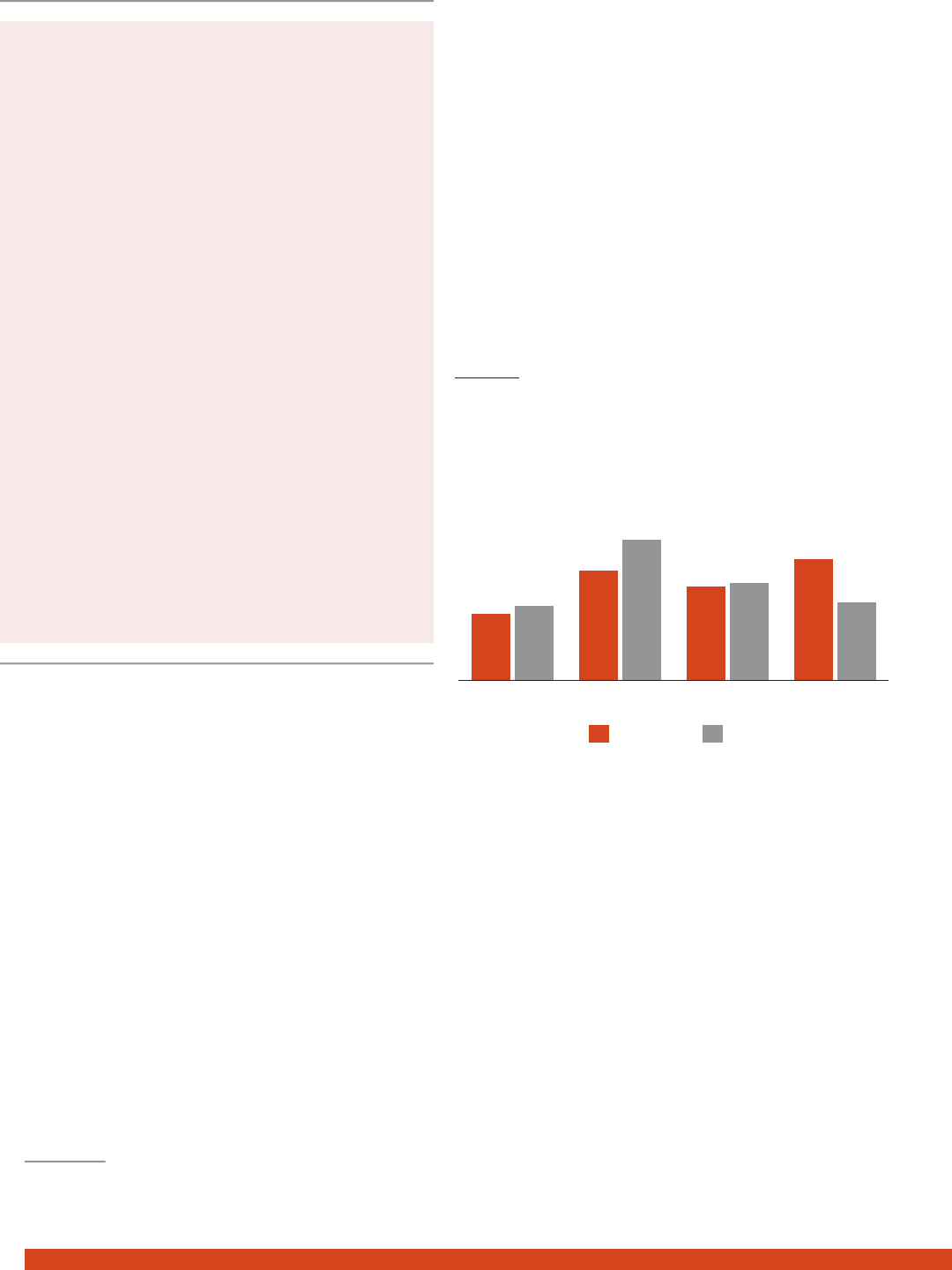

and older, but older adults are more concentrated in some

parts of the country than others. Although the share of the

total population that is ages 65 and older is not projected

to surpass 20 percent until 2028, one in every four counties

has already reached that level (see Figure 7, page 7). Older

Americans are most concentrated in Florida, the Appalachian

region, and parts of the upper Midwest and Northwest, but

many counties outside of these regions also have large and

growing shares of older adults—especially in rural areas.

Nationwide, more than three-quarters (77 percent) of counties

already have older populations at or above the national

average. Most of the counties with smaller shares of older

adults are located in Alaska and other western states.

boomers remains unmarried at ages 65 and beyond, the

number who live alone may also increase substantially after

2030, and is not likely to be completely offset by the modest

increase in cohabitation within this age group. The future

increase in the number of unmarried older adults who live

alone may also result in increased demand for home health

care and community-based social services.

TENURE AND HOUSING COST

In 2014, nearly four-fifths (78 percent) of householders ages

65 and older owned their homes, compared with only one-

fifth (22 percent) who were renters.

11

However, more than one

quarter (27 percent) of older homeowners spent 30 percent of

their monthly household income on housing expenses, which

is typically considered to represent a housing cost burden.

12

Only homeowners ages 15 to 24 had a higher share (34

percent) with a housing cost burden. Spending 30 percent or

more of their monthly income on housing costs leaves older

homeowners with less money for food, transportation, and

medical expenses, including costly prescription drugs. Such

housing cost burdens can negatively affect the health and

economic well-being of older Americans.

Less Than

High School

Highest Level of Educational Attainment of Men and Women Ages 65

and Older, 2014

High

School

Some

College*

Bachelor’s

or More

Men

Women

17%

19%

28%

36%

24%

25%

31%

20%

*Includes those with some college but no degree and those with associate’s degrees.

Source:

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2014.

FIGURE 6

More U.S. Men Than Women Ages 65 and Older Have

Bachelor’s Degrees.

BOX 1

Defi ning Housing Units and

Group Quarters

Most people reside in one of two types of living quarters:

housing units or group quarters. A housing unit is a house,

apartment, mobile home, group of rooms, or a single room

that is occupied as separate living quarters. Group quarters

are places where people live in a group living arrangement

that is owned or managed by an entity or organization

providing housing and/or services for the residents, such

as nursing homes or correctional facilities. Nursing and

skilled-nursing facilities are those that are licensed to provide

medical care with seven-day, 24-hour coverage for people

requiring long-term, non-acute care.

Housing that is specifi cally for the older population has

become much more prevalent, and is identifi ed by many

different names, such as senior apartments, independent

living, continuing care retirement communities, board and

care homes, and assisted living. Unless the living quarters in

these facilities meet the defi nition of nursing/skilled-nursing

facilities, they are generally considered to be housing units

as long as each resident’s living quarters are occupied as

a separate unit with direct access to the outside. Some of

these housing facilities may contain both housing units and

group quarters—which can make the distinction between

them confusing. For example, an assisted living complex

may have a skilled-nursing fl oor or wing that is considered to

be group quarters, while the rest of the living quarters in the

facility are considered housing units.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

7

Florida has been a longtime magnet for retirees, but other

parts of the country—particularly parts of the rural

Midwest—are “aging in place” because disproportionate

shares of young people have moved elsewhere. Population

aging in rural America is a consequence of job loss and

long-term outmigration of younger adults, and can be

associated with declining tax revenues, shrinking school

enrollments and neighborhoods, and declines in the

availability of services, such as health care.

Future state-level population trends depend, in part, on the

migration patterns of baby boomers as they reach retirement

age. States and local areas that are attractive to younger

retirees could see a surge in older population growth during

the coming decades.

Economic Security

The poverty rate for Americans ages 65 and older has

dropped sharply during the past 50 years, from nearly 30

FIGURE 7

Older Americans Make Up At Least 20 Percent of the Population in One-Quarter of U.S. Counties.

14.5% to 19.9%

20% or Greater

Less Than 10%

10% to 14.4%

Percent of Population Ages 65 and Older by County, 2014

U.S. Average: 14.5%

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau, 2014 Population Estimates.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

8

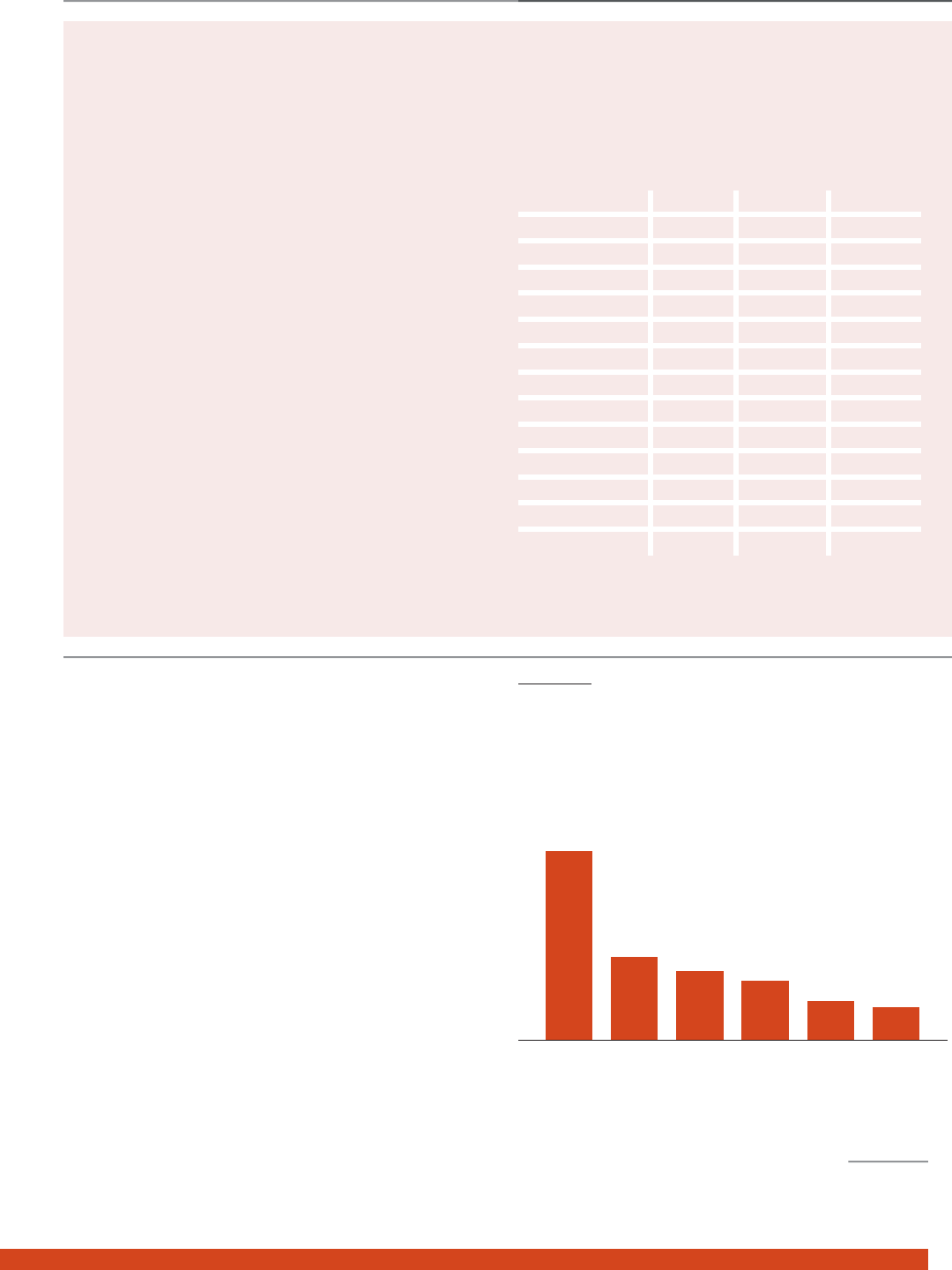

percent in 1966 to 10 percent today. In the early 1960s, the

poverty rate among older adults was much higher than that of

children and working-age adults. But the expansion of Social

Security, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, contributed

to a rapid decrease in poverty among older adults (see Figure

8). As Social Security expenditures increased, the poverty rate

among older adults declined, and has remained at relatively

low levels for more than three decades. In 2014, the poverty

rate among older adults was 10 percent, half the rate for

children (21 percent) and lower than the rate for adults ages

18 to 64 (14 percent).

Although Social Security keeps most older Americans out of

poverty, there are wide economic disparities across different

population subgroups. While just 8 percent of non-Hispanic

whites ages 65 and older lived in poverty in 2014, the

comparable figure was 18 percent among Latinos and 19

percent among African Americans.

Older women are especially vulnerable. In 2014, about 12

percent of women ages 65 and older were poor, compared

with 7 percent of older men. Among those ages 75 and older,

women are nearly twice as likely to be poor (15 percent)

compared with men (8 percent). The large disparity at older

ages can be explained, in part, by women’s longer life

expectancy compared to men and the fact that older women

are more likely to be living alone. But higher poverty among

older women is also linked to the gender gap in earnings at

younger ages, which translates into lower Social Security

payments for women in retirement.

15

Although widely cited, the official poverty rate has been

criticized because it fails to account for many important

household expenses and benefits. While the official poverty

rate shows a high level of economic security among older

Americans, alternative measures of economic well-being

tell a different story. For example, the Census Bureau’s

Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) puts the 2014 poverty

rate among older adults at 14.4 percent.

16

The higher poverty

rate for older adults under the SPM reflects the fact that SPM

poverty thresholds are not adjusted based on the age of the

householder, while thresholds for the official poverty rate are

set lower for households headed by older adults—resulting in

fewer impoverished older adults under the official measure.

High out-of-pocket health care expenses, such as payments

for prescription drugs, also contribute to higher poverty rates

for older Americans under the SPM.

17

Economic disparities among younger adults raise concerns

about the future health and well-being of older adults.

Inequalities among working-age adults by gender, race/

ethnicity, and education tend to persist in old age. Older

adults with more economic resources are in better health

and live longer, on average, than those with fewer resources.

Maintaining a strong social network provides an important

buffer against stress and depression, but poor older adults

are more likely to live in deteriorating neighborhoods where

there may be concerns about safety and fewer opportunities

for social contact.

18

Lower socioeconomic status has

also been linked to a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s

disease.

19

SOURCES OF INCOME

Older Americans rely on a combination of Social Security

benefits, pensions, retirement savings (including IRAs and

401(k)s), and earnings from full-time or part-time work. Since

the early 1960s, Social Security has provided about one-third

of the income of those ages 65 and older. The share provided

by pensions rose from 9 percent to about 18 percent

between 1962 and 1990, and has remained close to that level

since then.

20

Earnings from wages and salaries are also a major source of

income for older Americans. The share provided by earnings

has increased since the early 1990s, coinciding with the

rising labor force participation of older Americans. Asset

income (such as income from interest, dividends, or estates)

is the other major income source and accounted for about 9

percent of income in 2014, down substantially from the 1980s

and 1990s. The decline in asset income is largely due to the

drop in interest rates during the past several decades.

21

The mix of income sources varies significantly for older

Americans at the top of the income distribution compared

with those at the bottom (see Figure 9, page 9). Social

Security benefits, which are available at a reduced level at

Note:

Social Security payments are adjusted for infl ation.

Source:

U.S. Census Bureau and Social Security Administration.

FIGURE 8

As Social Security Benefi ts Have Expanded, the Poverty

Rate Among Americans Ages 65 and Older Has Declined.

Payments

Per Capita

Poverty

Rate (%)

1966 1974 1982 1990 1998 2006 2014

Poverty Rate

Social Security Payments

Poverty Rates and Per Capita Social Security Payments, 1966 to 2014

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

$18,000

$16,000

$14,000

$12,000

$10,000

$8,000

$6,000

$4,000

$2,000

$0

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

9

age 62, provide about 76 percent of income among lower-

income households headed by adults ages 65 and older,

while Social Security accounts for just 21 percent of income

among higher-income households headed by older adults.

Earnings account for 43 percent of income among higher-

income households, nearly four times the share among

lower-income households (12 percent). Asset income from

savings, investments, and rental income also accounts for a

higher share of income among higher-income households (12

percent), compared with lower-income households (2 percent).

Older racial/ethnic minorities are especially dependent on

income from Social Security because they are less likely to

have income from pensions, earnings, or assets. In 2013,

about one-fifth of African American and Latino older adults

relied solely on Social Security for their family income,

compared with 13 percent of white older adults.

22

WORKING LONGER

The U.S. labor force is growing older. In 2014, adults ages 55

and older made up about 22 percent of the labor force, up

from 12 percent in 1990. By 2022, their share is projected to

increase to 26 percent.

23

The recent graying of the labor force is linked to the large

cohort of baby boomers who are nearing retirement age

and rising employment rates among older adults, as well as

the increasing college enrollment and declining labor force

participation rates among working-age adults. The recession

also contributed to the rising share of older Americans in the

labor force, by putting pressure on older workers to stay on

the job (see Box 2, page 10).

Labor force participation rates among older adults declined

for several decades following World War II. Between 1950

and 1993, the percentage of those ages 55 and older in

the labor force fell from 43 percent to 29 percent. Earlier

retirement became common in the 1970s and 1980s, creating

a social class of healthy, active, and financially comfortable

retirees. The average retirement age among men fell from

nearly 67 years in the early 1950s to 62 years in the late

1990s, with a similar decline among women.

But since the 1990s, these trends have reversed. Rising

labor force participation rates among older adults have been

linked to a combination of factors. Employer pensions and

medical benefits for retirees have been largely replaced by

employee-funded defined contribution plans, such as 401(k)s.

Mandatory retirement ages have been abolished for older

adults in many industries—clearing the way for employees

to work after age 60 or 65. The age at which workers can

receive full Social Security benefits has increased from 65

to 66 or 67 for those born after 1942. The tax penalty for

earning income while receiving Social Security benefits has

been reduced. And older Americans are in better health and

living longer, making it possible to work into older ages (see

page 12).

While some older workers have stayed on the job, others

have left the workforce and reentered it. Data from the Health

and Retirement Study have shown that about 15 percent of

older adults have reentered the labor force after retirement.

24

Others have continued to work beyond traditional retirement

age but on a part-time basis. In 2014, about 40 percent of

employed adults ages 65 and older usually worked less than

35 hours per week, compared with 18 percent of working-

age adults (ages 16 to 64).

25

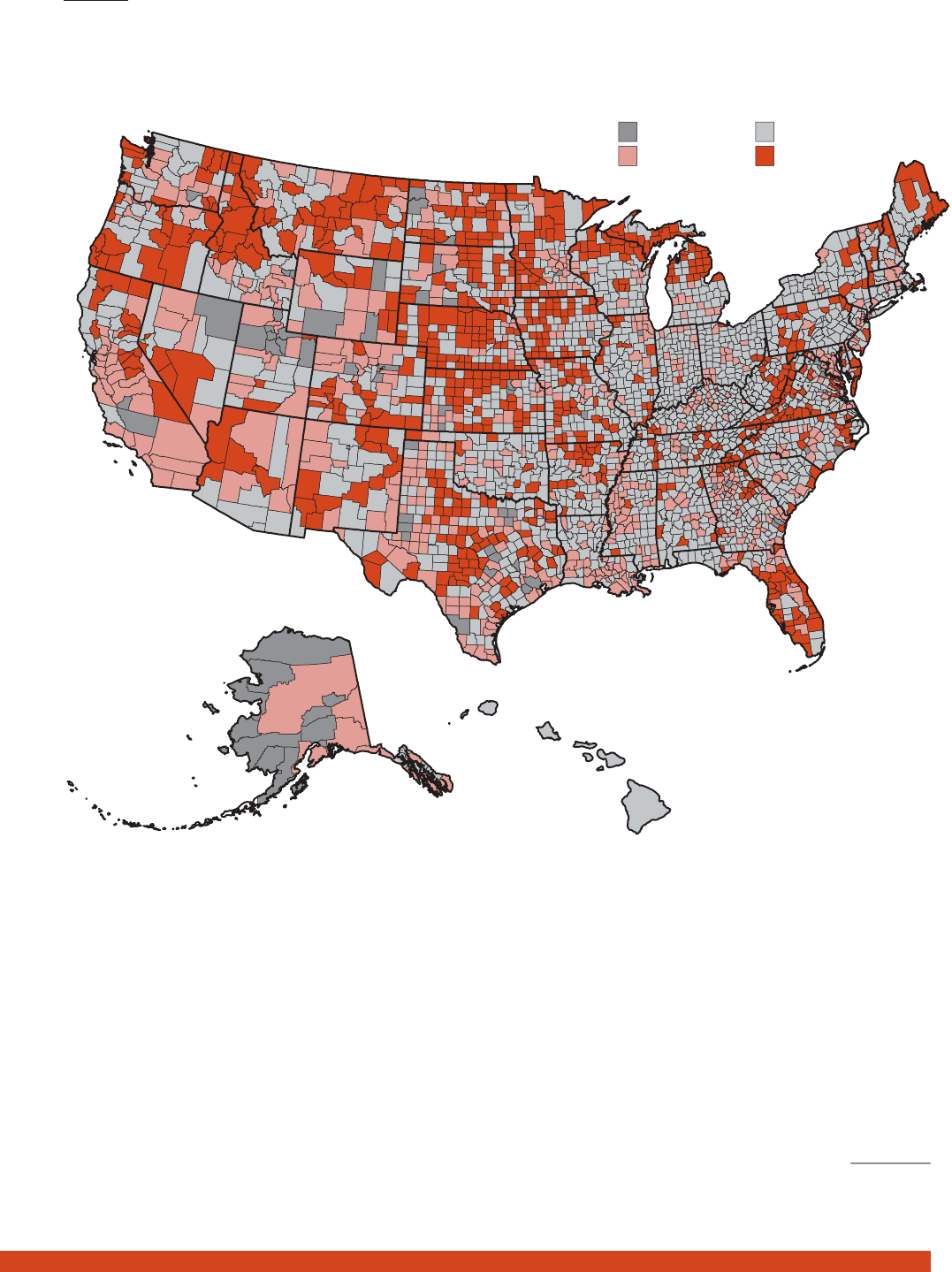

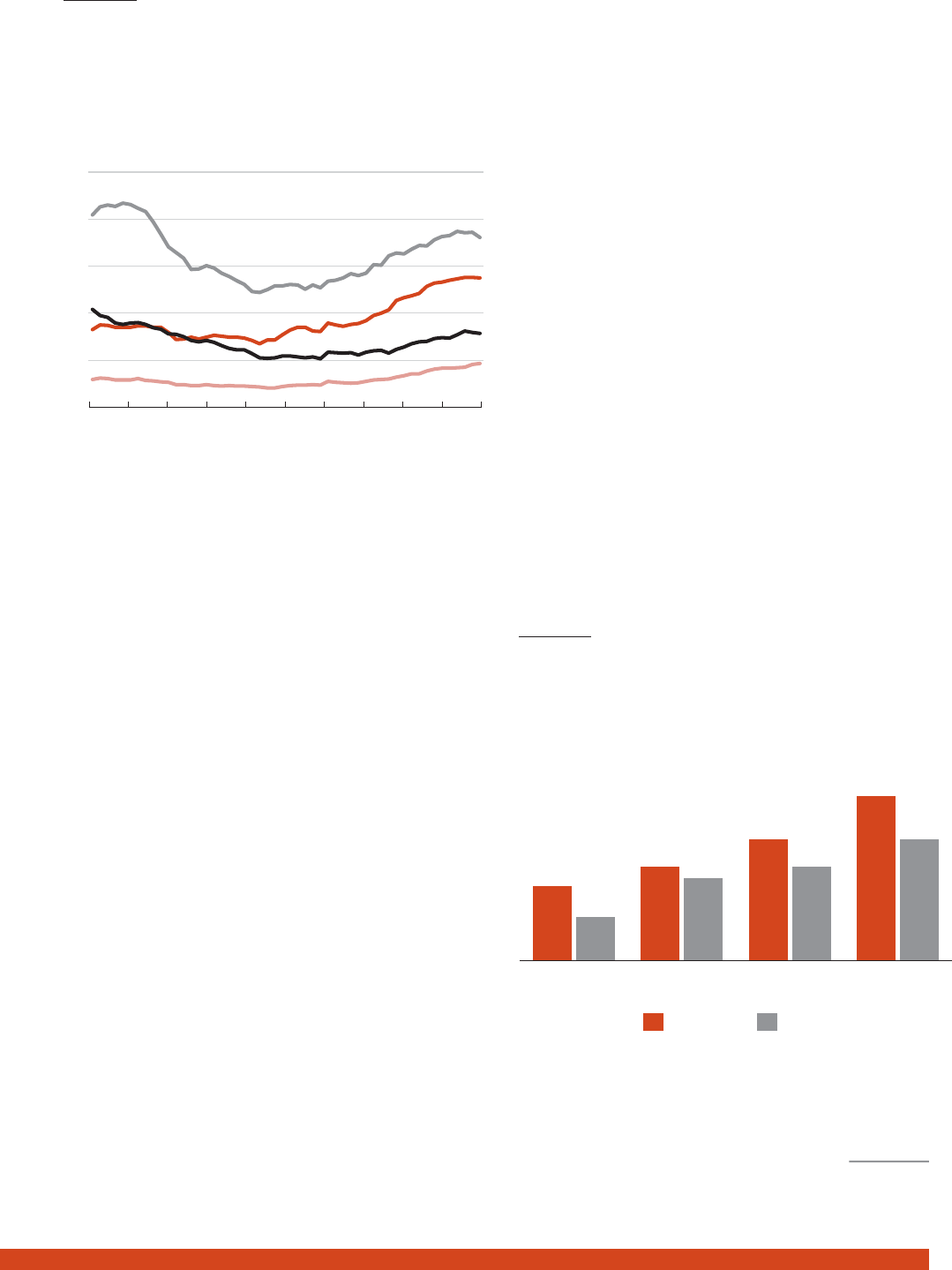

By 2014, 23 percent of men and about 15 percent of women

ages 65 and older were in the labor force, and these levels

are projected to rise further by 2022, to 27 percent for men

and 20 percent for women.

26

Labor force participation is

considerably higher among those ages 65 to 69 than those

ages 70 and over. However, the share of older adults in the

workforce rose sharply among both age groups after the mid-

to-late 1990s (see Figure 10, page 11).

Among men, the labor force participation rate of those ages

65 to 69 dropped from 43 percent in the mid-1960s to 24

percent by the mid-1980s before increasing to its current level

(36 percent). During the past few years, older men’s labor

force participation rates have declined slightly—especially

among 65-to-69-year-olds—as many baby boomers who had

delayed retirement during the recession have started to exit

the workforce.

27

FIGURE 9

Social Security Is the Primary Income Source for Older

Americans With Low Incomes.

Total

Shares of Aggregate Income for Households Headed by Adults Ages 65 and

Older in Different Income Categories, by Source, 2014

Earnings Social Security Assets Pensions Other

Medium-Income Lower-Income Higher-Income

3%

20%

9%

34%

35%

6%

5%

2%

76%

12%

3%

17%

4%

52%

24%

2%

23%

12%

21%

43%

Note:

Lower-Income = below 200% of the poverty line, Medium-Income = 200%–399%

of the poverty line, and Higher-Income = 400% of the poverty line or higher. Numbers may

not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Source:

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2015 Annual Social and

Economic Supplement.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

10

BOX 2

Effect of the Great Recession on Older Adults

The Great Recession (2007 to 2009) had wide-ranging

economic effects on Americans of all ages, but older

people were relatively insulated from the prolonged

economic downturn. Adults ages 65 and older were more

likely to be retired, so they were less likely to experience job

loss. They were more likely to own their homes outright, so

they were less likely to fall behind on payments or lose their

homes to foreclosure. And while poverty rates increased

sharply among children and working-age adults during

the recession, the poverty rate for retirement-age adults

remained unchanged, largely because of their access to

Social Security benefi ts.

1

Although young adults in their 20s and 30s bore the brunt

of the economic downturn, many Americans ages 50 and

older were also affected, either directly or indirectly, by

rising unemployment, falling home values, and the decline

in the stock market. Moreover, many older adults who were

not directly affected by the recession had children or other

family members who were. Data from the American Life

Panel (a series of Internet surveys of 2,500 adults ages

18 and older) show that fi nancial help during the recession

fl owed primarily from older parents to adult children.

2

Effects on Wealth and Spending

Households headed by older adults are wealthier, on

average, compared with households headed by younger

adults. In 2007, the median net worth of households

headed by adults ages 65 and older was about $257,000,

more than twice that of households headed by adults ages

35 to 54 ($100,000).

3

Older adults not only had more wealth

to lose during the recession, but also have less time to

wait for values in the stock or housing markets to recover,

compared with younger adults.

Between 2007 and 2011, median net worth declined by

$64,000 among households headed by adults ages 65 and

older, compared with a $60,000 decline among households

headed by adults ages 35 to 54. However, in percentage

terms, households headed by older adults experienced

smaller declines in wealth during the recession relative to

households headed by younger adults. Among households

headed by adults ages 65 and older, net worth declined by

25 percent between 2007 and 2011, compared with a 61

percent decline among households headed by 35-to-54-

year-olds.

4

Using a broader wealth measure that includes the future

value of Social Security payments and defi ned benefi t

pensions, the effects of the recession on older adults’

wealth were generally modest and by 2012, households

headed by older adults had recovered most of the wealth

they lost during the recession.

5

A recession can also affect consumption patterns as individuals

who become unemployed may reduce spending to make up

for the loss of income. Others may reduce spending because

they feel they are at risk of losing their job.

6

For older Americans,

cutting back on spending could mean rationing health care

spending through fewer doctor visits, screening tests, or

prescription drugs. Evidence from the Health and Retirement

Study (HRS) indicates that about one-third of those ages 55 to

64 reduced spending during the recession, compared with just

17 percent of those ages 75 and older, suggesting that older

adults were more insulated from the recession’s impacts.

Effects on Employment and Retirement Plans

Recessions can affect retirement expectations by putting

pressure on older workers to stay on the job, and HRS data

show that older workers are more inclined to delay retirement

when unemployment rates are increasing. This expectation to

continue working is especially true of workers who are closest

to retirement age, and those with high levels of debt.

7

Millions of people lost their jobs during the recession including

many older workers who experienced long-term unemployment

and eventually dropped out of the labor force. But overall,

the economic downturn had only modest effects on the

employment status of those nearing retirement age (ages 53

to 58). Unemployment increased sharply, but these job losses

were partly offset by employment gains among baby boomers

who postponed retirement.

8

While macroeconomic factors can affect retirement expectations

and trends, individual, family, and job characteristics also play

an important role. Older adults who are racial/ethnic minorities,

in poor health, and those with lower levels of education tend to

retire earlier than other groups. Certain jobs, such as those with

signifi cant physical requirements, can also force older adults into

early retirement.

References

1 Loraine A. West et al., “65+ in the United States: 2010,” Current Population Reports

P 23-212 (June 2014).

2 Susann Rohwedder, “Helping Each Other in Times of Need: Financial Help as a

Means of Coping With the Economic Crisis.” RAND Occasional Paper OP-269,

(2009).

3 Fabian T. Pfeffer, Sheldon Danziger, and Robert F. Schoeni, “Wealth Disparities

Before and After the Great Recession,” Annals of the American Academy of Political

and Social Science 650, no. 1 (2013): 98-123.

4 Pfeffer, Danziger, and Schoeni, “Wealth Disparities Before and After the Great Recession.”

5 Alan L. Gustman, Thomas L. Steinmeier, and Nahid Tabatabai, “The Great

Recession, Decline and Rebound in Household Wealth for the Near Retirement

Population,” Journal of Retirement 2, no. 2 (2014): 27-44.

6 Michael D. Hurd and Susann Rohwedder, “Expectations and Household Spending,”

Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Brief 287 (2013).

7 Maximiliane E. Szinovacz, Lauren Martin, and Adam Davey, “Recession and Expected

Retirement Age: Another Look at the Evidence,” The Gerontologist 54 no. 2 (2014).

8 Gustman, Steinmeier, and Tabatabai, “The Great Recession, Decline and Rebound

in Household Wealth for the Near Retirement Population.”

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

11

Women ages 65 to 69 also saw a gradual increase in labor

force participation over the period, but with a 2014 level that

exceeds the 1964 level by a considerable margin—27 percent

versus 18 percent. While labor force participation among

men ages 70 and over was still lower in 2014 than in the early

1960s, the rate among women in this age group is higher than

it has ever been in the last five decades.

An important consequence of longer life expectancy is that

people need to finance more years of retirement. Americans

are becoming aware that retiring at age 62 could easily

require 30 or more years of retirement income, giving them an

incentive to hold onto their jobs a little longer.

Many policymakers have proposed to increase the age

at which older adults are eligible for full Social Security

benefits—currently set at 67 for those born in 1960 or later—

to reflect longer life expectancies and to reduce costs. In

addition to broader fiscal savings, working longer can have

significant benefits to individuals. A 2010 study found that

workers who retired in their early 60s had reduced cognitive

ability compared with those who worked up to or beyond

retirement age.

28

But for many older adults, staying on the job is not an

option. Among Social Security beneficiaries, those who

are less educated, less healthy, and working in blue-

collar, physically-demanding jobs are more likely to take

benefits early compared with more highly-educated white-

collar workers.

29

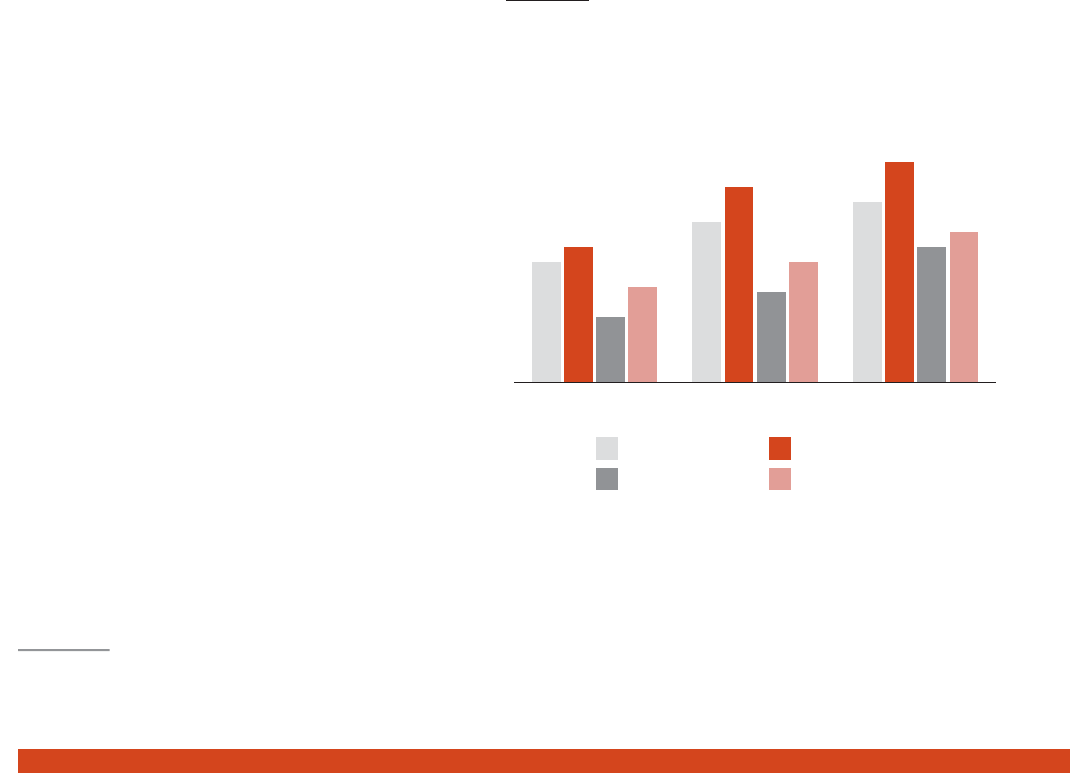

In fact, men ages 65 to 74 with at least

a bachelor’s degree are more than twice as likely to be

in the labor force compared with those with less than a

high school diploma. And college-educated older women

are nearly three times more likely to be in the labor force

than their female counterparts who did not graduate from

high school (see Figure 11). Age discrimination also limits

employment opportunities among many older Americans.

Despite federal laws barring age discrimination, some firms

continue discriminatory practices in terms of hiring decisions,

workplace policies, or opportunities for advancement for

older adults.

30

This gap in labor force participation rates by education level

has increased over time, leaving less-educated older adults

more dependent on Social Security relative to those with

college degrees, who have more income from earnings and

retirement savings.

Health and Well-Being

By many measures, the U.S. older population is healthier than

previous generations. Older adults are living longer, disability

is less prevalent at the oldest ages, and old age is less likely

to mean death or loss of physical or mental functions. But

there are wide gaps in the health of older adults among

different racial/ethnic groups. And Americans have shorter

life expectancies, on average, compared with people in most

other high-income countries.

The increase in life expectancy has also been accompanied

by an increase in older Americans living with chronic

conditions. There are signs that baby boomers who are

approaching retirement age are in worse health compared

with previous generations. Changes in physical health among

older adults are important not only because they can affect

FIGURE 11

College-Educated Americans Are More Likely to Be in the

Labor Force After Age 65.

Less Than

High School

Labor Force Participation Rates of Older Adults Ages 65-74,

by Education and Sex, 201

4

High School Some College*

Men

Women

19%

11%

24%

21%

31%

24%

42%

31%

Bachelor’s

or More

*Includes those with some college but no degree and those with associate’s degrees.

Source:

U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2014 Annual Social and

Economic Supplement.

FIGURE 10

The Share of U.S. Men and Women Ages 65 and Older in

the Labor Force Has Grown Since the 1990s.

Percent of Men and Women Ages 65 and Older in the Labor Force,

1964 to 2014

1964 1969 1974 1979 1984 1989 1994 1999 2004 2009 2014

Men Ages 65-69

Men Ages 70+

Women Ages 65-69

Women Ages 70+

0

10

20

30

40

50

43%

36%

20%

18%

27%

16%

9%

6%

Source:

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

12

daily activities and the need for long-term care, but also

because of the potential long-terms effects on mental health

and happiness in old age.

LIFE EXPECTANCY

Americans live longer than they did in the past, but life

expectancy in the United States continues to lag behind that

of many other high-income countries. U.S. life expectancy

increased from 68 years in 1950 to 79 years in 2013, in large

part due to the reduction in mortality at older ages.

31

But as of

2012, the United States ranked 27th out of 34 Organization

for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

countries in overall life expectancy.

32

Lower life expectancy in

the United States reflects, in large part, early deaths related

to higher rates of tobacco use and obesity compared with

other countries, according to recent studies by the National

Research Council.

33

There are wide gaps in life expectancy across different racial/

ethnic groups. At age 50, white men in the United States may

expect to live (on average) another 30 years and white women

another 33 years.

34

However, older black men and women

may not expect to live as long—27 and 31 years, respectively.

Conversely, African Americans who survive until age 85 may

expect to live slightly longer than whites of the same age.

Although the white-black mortality gap has persisted over time,

there are signs that this gap is starting to narrow. Between

1999 and 2013, mortality rates have increased among white,

middle-aged men and women in the United States, partly

because of rising death rates from drug and alcohol abuse

(including prescription painkillers), suicide, and chronic liver

diseases and cirrhosis. During the same period, mortality rates

among blacks and Latinos have continued to fall.

35

Women in the United States continue to live longer than

men, on average, but the gender gap in life expectancy has

narrowed in recent years (see Box 3, page 13).

DISABILITY AND HEALTHY AGING

Healthy life expectancy at age 70—the number of years a

person may expect to live disability-free—has been on the

rise.

36

Between 1992 and 2008, overall life expectancy at age

65 increased by 1.3 years while disability-free life expectancy

increased by 1.8 years. The increase in life expectancy free of

disability has been linked to improvements in the prevention

and treatment of certain diseases—especially severe heart

disease and vision problems among older adults.

37

However, disability levels among older adults may increase

in the coming years because of relatively high disability rates

among baby boomers who are now reaching retirement age.

Although baby boomers (ages 51 to 69 in 2015) are living

longer than their parents’ generation and are less likely to

smoke, have emphysema, or have heart attacks, they are

also more likely to be obese or have diabetes or high blood

pressure than the previous generation at similar ages.

38

Being either overweight or underweight at older ages may

signal health problems. Undernutrition is associated with

more deaths after age 70, and obesity is a risk factor for a

variety of chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension,

high cholesterol, heart disease, arthritis, and some cancers.

39

Lifestyle changes such as regular exercise instead of or

in addition to medication can be used to manage chronic

diseases and weight.

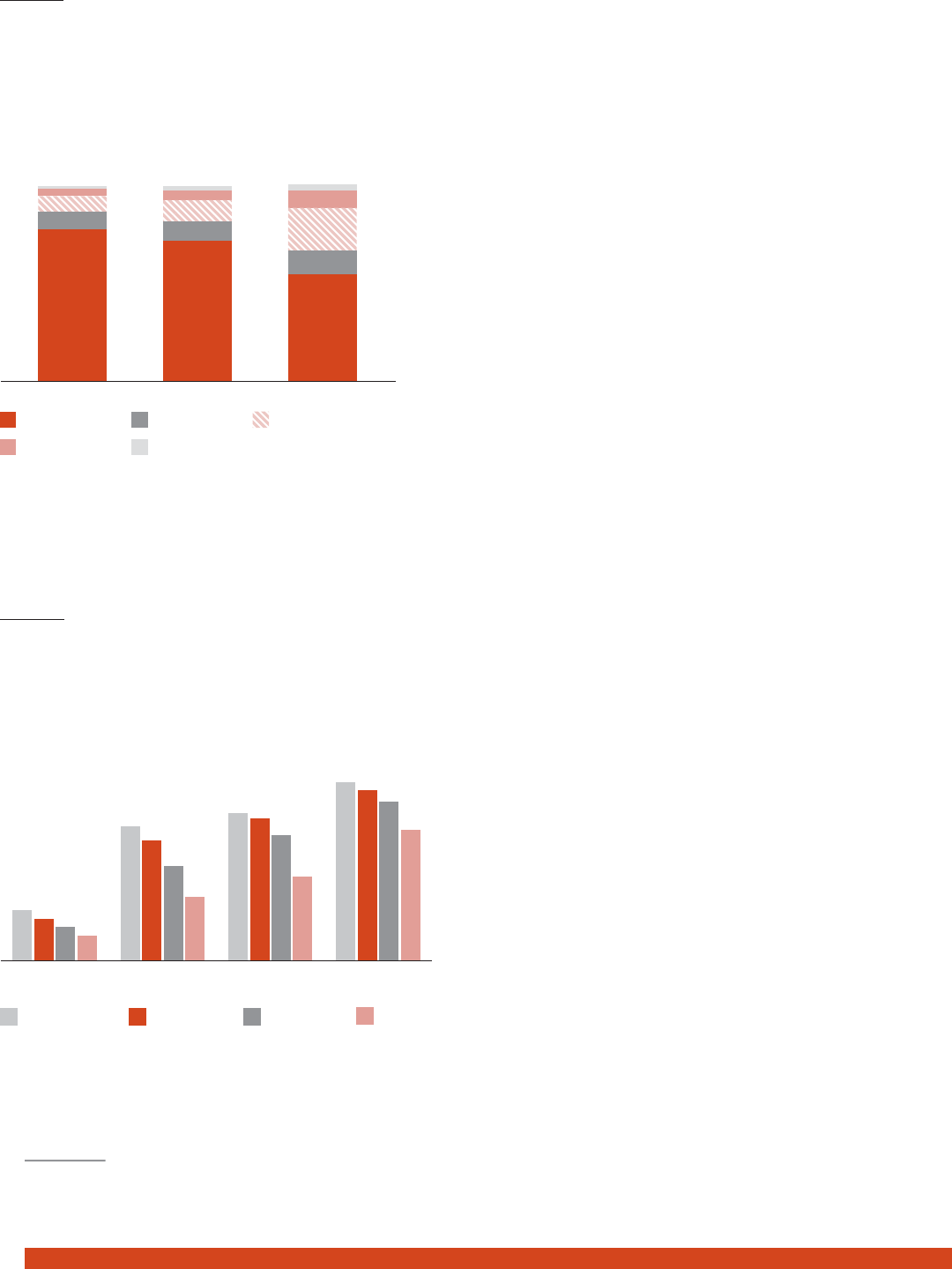

Recent analyses of U.S. obesity trends using the National

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey show a significant

increase in obesity prevalence among older adults between

1988 and 2012 (see Figure 12). Among the “young old” (ages

65 to 74), the share of men who were obese increased from

24 percent to 36 percent over the two-decade period from

1988-1994 to 2009-2012. Over the same period, the share

of women ages 65 to 74 who were obese increased from 27

percent to 44 percent. Obesity rates also increased among

men and women ages 75 and older, although rates were

lower for that age group.

Older adults are less active than those in younger age groups,

but regular physical activity is important for older adults to

stay healthy and disability-free. In a randomized study of

older adults with physical limitations, those who participated

in a physical activity program over a two-year period were

less likely to experience a major disability compared with

those who participated in a health education program.

40

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)

FIGURE 12

Obesity Continues to Increase Among Older Americans.

1988-1994 1999-2002 2009-2012

Men Ages 65-74

Adults Ages 65 and Older Who Are Obese, by Sex and Age Group,

1988 to 2012

Women Ages 65-74

Men Ages 75+ Women Ages 75+

24%

27%

13%

19%

32%

39%

18%

24%

36%

44%

27%

30%

Note:

Data are based on measured height and weight. Obese is defi ned by having a body

mass index (BMI) of 30 kilograms/meter or greater.

Source:

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health

Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

13

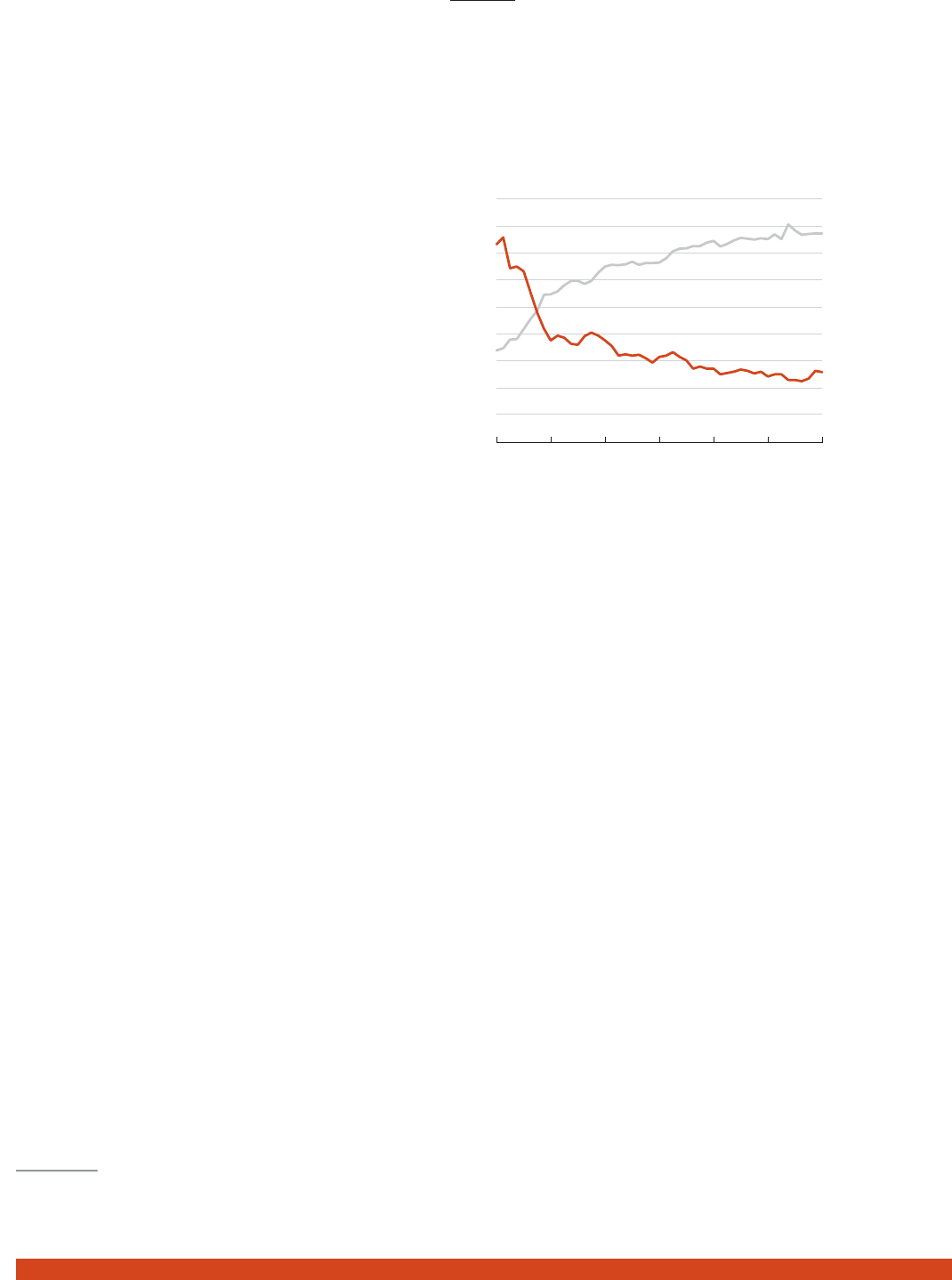

BOX 3

Narrowing Old-Age Gender Gap in the United States Linked to

Declines in Smoking

Women live longer than men in the United States and in nearly

every country in the world. But in the United States and many

other developed countries, this gender gap is narrowing,

resulting in an increase in the number of men, relative to women,

surviving to old age.

In 1990, there was a seven-year gap in life expectancy between

U.S. men and women. By 2013, this gap had narrowed to less

than fi ve years. It is not that women are dying sooner, but that

men’s life expectancy is increasing at a faster pace. In 2013, life

expectancy at birth was 76.4 years for males and 81.2 years for

females. But if current trends continue, men’s life expectancy

could approach that of women within the next few decades.

The growing number of men surviving to older age groups,

relative to women, is contributing to a rising sex ratio—the

number of males per 100 females—at older ages. The latest data

from the U.S. Census Bureau show that in 2014, there were 79

men ages 65 and older for every 100 women in that age group—

up from 67 older men per 100 older women in 1990 (see Figure).

By 2030, the Census Bureau projects that the sex ratio for older

adults will increase to 82 men per 100 women.

The data for adults ages 85 and older are even more striking.

The sex ratio has increased sharply among the “oldest old,”

from 39 older men per 100 older women in 1990 to 52 in 2014.

Census Bureau projections show that the sex ratio for those

ages 85 and older could rise to 62 by 2030. That represents 24

additional men for every 100 women in the oldest-old category,

compared with the 1990 estimate.

In the United States, researchers have linked the decline in the

gender gap in mortality to male and female patterns of smoking,

which increases the risk of death from lung cancer, heart disease,

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stroke. During the fi rst

half of the 20th century, smoking prevalence rates among men

and women converged, as men’s rates declined from their earlier

peaks and women’s rates increased—leading to a rise in smoking-

related deaths among women relative to men.

1

Smoking prevalence

peaked among women born in the early 1940s, whereas prevalence

rates peaked for men born in the 1910s. The result has been a

steady reduction in smoking-related deaths among older men and

an increase in deaths among older women.

Similar declines in the gender gap in life expectancy have been

reported in several countries in Europe. In France, the narrowing

gap has been linked to reductions in male deaths due to heart

disease and lung cancer. Improvements in men’s cardiovascular

health, relative to women, has also helped reduce the gender gap

in mortality in England and Wales, Sweden, Switzerland, and Italy.

2

The gender gap at older ages is narrowing across all racial/

ethnic groups, but the trend is most evident for non-Hispanic

whites. Between 2000 and 2014, the number of white men ages

65 and older per 100 white women in that age group increased

from 71 to 80—the largest increase among any of the major

racial/ethnic groups.

The sex ratio is also increasing among African Americans, but

the number of older African American men is still lagging far

behind the number of older women. In 2014, there were just

67 African American men per 100 African American women

ages 65 and older. This imbalance is linked to the high rates of

premature death among African American men. In 2013, the

average life expectancy for black males at birth was just 72

years—well below the average for black females (78 years) and

the U.S. average (79 years).

References

1 Samuel Preston and Haidong Wang, “Sex Mortality Differences in the United States:

The Role of Cohort Smoking Patterns,” Demography 43, no. 4 (2006): 631-46.

2 France Meslé, “Gender Gap in Life Expectancy: The Reasons for a Reduction of

Female Advantage,” Revue d’Epidémiologie et de Santé Publique 52, no. 4 (2004):

333-52.

Number of Older Men for Every 100 Older Women,

by Age Group, 1990, 2014, and 2030.

Ages 65+ Ages 65 to 84 Ages 85+

1990 2030 (Projected)2014

67

79

82

71

84

85

39

52

62

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

14

recommends a combination of weekly aerobic activity and

muscle-strengthening activities for older adults. However,

in 2013, just 12 percent of older adults met HHS physical

activity guidelines.

41

Cognitive health is another important dimension of healthy

aging. Older Americans who experience a decline in cognitive

ability, which can range from mild cognitive decline to

dementia, are more likely to need regular assistance with daily

activities. Those with severe cognitive disabilities tend to rely

heavily on informal care from family members.

42

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia and

is characterized by memory loss and a progressive decline in

cognitive abilities. Nearly 5 million Americans were living with

Alzheimer’s disease in 2013, but this number could increase

to 14 million by 2050 with the aging of the U.S. population.

43

Researchers estimate that Alzheimer’s and other forms of

dementia cost the United States between $157 billion and

$215 billion in long-term care and medical expenses each

year—more than either heart disease or cancer.

44

HAPPINESS

As older Americans live longer, there is growing interest in

exploring the connections between health and happiness

in order to improve the overall quality of life in later years.

This line of research, known as subjective well-being, goes

beyond traditional measures of physical and cognitive health

to understand the emotional dimension of older adults’ lives,

examining whether people perceive their day-to-day existence

as positive and rewarding or negative and distressing.

In the United States and many other higher-income countries,

life satisfaction follows a U-shaped pattern. Happiness falls to

its lowest levels among those ages 45 to 54 before increasing

among those in older age groups.

45

Adults ages 50 and

older report the highest levels of subjective well-being and

are happiest while socializing, working or volunteering, and

exercising.

46

Among older married adults, those with disabilities report

lower levels of life satisfaction compared with those without

disabilities, partly because disabilities limit physical and

social activity.

47

Disability can also put significant physical

and emotional stress on spouses and others who provide

informal care. But research suggests that the quality of a

marriage can mediate this relationship: Troubled marriages

take an emotional toll, whereas high-quality marriages can

buffer against later life stressors, such as providing care to a

disabled spouse.

48

Challenges and Opportunities

The rising number of older Americans will put pressure on

entitlement programs and create challenges for the labor

market and health care systems—as well as family members

who provide the majority of care to older adults with

disabilities.

The United States is not alone in facing the challenges of

an aging population. In fact, the U.S. population is aging at

a slower pace than in many other developed countries (see

Box 4, page 15). The total population in some countries, such

as Japan, is declining because there are not enough births

or migrants to offset the aging of the population. The U.S.

population is still relatively young compared with Japan and

many countries in Europe, but population aging in the United

States will accelerate during the next 30 years.

Most news stories on the topic of U.S. population aging

have focused on the potential negative social and economic

consequences of an aging society. However, the growth

in the older population is a success story from a public

health perspective, as new advances in medicine and living

standards have led to longer life expectancies. Policymakers

can take steps to minimize the negative economic impacts

of population aging by strengthening laws against age

discrimination and providing incentives for older adults to

stay in the labor force beyond the traditional retirement age.

FISCAL CHALLENGES

Two major entitlement programs in the United States—Social

Security and Medicare—have played an important role in

reducing poverty and improving the health and well-being

of the older population. However, the costs of these two

programs are projected to rise rapidly as the U.S. population

ages. The number of people receiving Medicare benefits will

increase by one-third during the next decade, according

to the Congressional Budget Office. Social Security and

Medicare expenditures are projected to make up a combined

12 percent of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by

2050, up from 8 percent today (see Figure 13).

FIGURE 13

Social Security and Medicare Expenditures Are Projected

to Reach a Combined 12 Percent of GDP by 2050.

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050

Social Security

Projected Social Security and Medicare Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP

Medicare

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

6%

6%

3%

1%

Source:

Social Security Administration, Summary of the 2014 Annual Reports.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

15

Many policymakers and planners are concerned about the

relatively fewer workers who will be supporting a growing

retired population. One way to evaluate social support needs

is through the elderly support ratio—the number of working-

age adults ages 18 to 64 for every person age 65 or older.

Of course, the elderly support ratio is just an approximation

because some people stop working before they reach age 65

and an increasing number are continuing to work into their

late 60s and early 70s.

The elderly support ratio dropped from about 14 working-

age adults per person age 65 or older at the turn of the 20th

century to 5 at the beginning of the 21st century. By 2014,

there were approximately 4 working-age persons per older

adult, and the ratio could drop to about 2 by 2060, according

to the latest Census Bureau projections (see Figure 14).

Although population aging will create fiscal challenges,

many argue that these challenges can be managed through

structural changes to existing entitlement programs, an

increase in retirement savings among workers, and by

shifting retirement to later ages. Improved health and longer

FIGURE 14

By 2030, There Will Be Only About Three Working-Age

Adults For Every Person Age 65 or Older.

13.6

6.0

1900 1960 2000

Elderly Support Ratio*

2014 2030 2060

5.0

4.3

2.8

2.4

*Number of persons ages 18 to 64 for every person age 65 or older.

Source:

PRB analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

BOX 4

Aging Populations Challenge Countries Worldwide

Population aging is a global trend impacting both developed

countries and less developed nations. At 26 percent, Japan’s

older population has already surpassed the share of older adults

projected for the United States by 2050 (see Table). In Germany

and Italy, the share of older adults is projected to increase from

about one-fi fth of the population today to about one-third by

2050. Rapid population aging is also expected in parts of Asia

and Latin America, including Brazil, China, India, and Mexico. In

China, it’s projected that there will be 371 million people ages 65

and older in 2050—more than the entire 2015 U.S. population.

Global population aging will put pressure on social and economic

support systems—especially in countries like China, where rapid

economic development and low fertility levels have reduced

the availability of family caregivers.

1

Countries with aging

populations will also experience increases in noncommunicable

diseases, such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and lung

disease—ailments that are more common among older adults.

On a positive note, global population aging refl ects the broader

health transition that is taking place in developing countries,

characterized by reductions in fertility, child and adult mortality,

and infectious disease.

2

References

1. Richard Jackson, “The Aging of China” (2010), accessed at

http://csis.org/publication/aging-china-0, on Nov. 4, 2015.

2. National Institute on Aging, “Why Population Aging Matters: A Global Perspective,”

accessed online at www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/why-population-aging-

matters-global-perspective, on Nov. 4, 2015.

The U.S. Population Is Aging at a Slower Pace Than Many

Other Developed Countries.

Percent of the Population Ages 65 and Older

1980 2015 2050

U.S. 11 15 22

Japan 9 26 36

Italy 13 22 35

Germany 16 21 32

China 5 10 28

France 14 19 26

United Kingdom 15 18 25

Brazil 4 8 23

Russia 10 13 21

Mexico 4 7 19

India 4 6 14

Egypt 5 5 10

Uganda 3 3 4

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision; and U.S. Census Bureau,

Population Estimates and Projections.

www.prb.org

POPULATION BULLETIN 70.2 2015

16

life expectancy among older adults is paving the way for

employment well beyond the traditional retirement age of

65.

49

In 1950, the average man retiring at age 65 could expect

to live another 13 years, and a 65-year-old woman another

15 years. Today, men average an additional 17.9 years and

women another 20.5 years beyond age 65.

CARING FOR AN AGING POPULATION

As the U.S. population grows older, there will be a steady

increase in the number of older adults with functional and

cognitive disabilities. Historically, older adults have relied

heavily on their adult children to provide support and care

when they needed assistance. This is especially true among

older women, who are much more likely than older men to

be living alone. However, recent trends in marriage and family

patterns may limit the availability of adult children who are

available—or willing—to provide care for older parents in the

coming decades. More young adults are delaying marriage,

and in 2013, 41 percent of births occurred outside of marriage,

up from 33 percent in 2000. As a result, more children are

growing up in single-parent families and “blended families”

made up of a couple and their children from current and

previous relationships. Studies have shown that children's

complex living arrangements may lead to weaker family ties

and less support for aging parents.

50

With more men surviving to old age, more potential partners

and caregivers are available for older women (see Box 3,

page 13). However, the reality of caregiving is more complex

because of the rising number of older adults who are single.

Nearly half of female baby boomers will have been divorced

by age 65, according to recent estimates.

51

Although many

of these women have remarried, there has also been a rapid

increase in older adults who are single or cohabiting.

52

Given

these changes in marriage and family patterns, it is too soon

to tell whether men’s longer life expectancy will translate into

better support mechanisms for older women, or if these gains

will be offset by broader social trends.

A growing number of older adults with disabilities rely on

assistive devices and technologies (walkers and scooters,

for example) to maintain their independence. In fact, one of

the key goals of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act

was to promote the use of assistive technologies and public

accommodations for persons with functional or cognitive

limitations. However, whites and those with higher income

and education are more likely to use these technologies

compared with minorities and those with lower socioeconomic