Boshoff, C.; Gray, B.

Article

The relationships between service quality, customer

satisfaction and buying intentions in the private

hospital industry

South African Journal of Business Management

Provided in Cooperation with:

University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB), Bellville, South Africa

Suggested Citation: Boshoff, C.; Gray, B. (2004) : The relationships between service quality, customer

satisfaction and buying intentions in the private hospital industry, South African Journal of Business

Management, ISSN 2078-5976, African Online Scientific Information Systems (AOSIS), Cape Town,

Vol. 35, Iss. 4, pp. 27-38,

https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v35i4.666

This Version is available at:

https://hdl.handle.net/10419/218311

Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen:

Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen

Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden.

Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle

Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich

machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen.

Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen

(insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten,

gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort

genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.

Terms of use:

Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your personal

and scholarly purposes.

You are not to copy documents for public or commercial purposes, to

exhibit the documents publicly, to make them publicly available on the

internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public.

If the documents have been made available under an Open Content

Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you may exercise

further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 27

The relationships between service quality, customer satisfaction and

buying intentions in the private hospital industry

C. Boshoff* and B. Gray

Department of Business Management, University of Port Elizabeth

PO Box 1600, Port Elizabeth 6000, Republic of South Africa

Received August 2004

The objective of this study was to investigate whether superior service quality and superior transaction-

specific customer satisfaction will enhance loyalty (as measured by purchasing intentions) among patients in

the private health care industry. The research design allowed an assessment of the relative impact of

individual dimensions of service quality and transaction-specific customer satisfaction on two dependent

variables, namely loyalty (as measured by intentions to repurchase) and customer satisfaction, the latter

measured as ‘overall’ or cumulative satisfaction.

The results reveal that the service quality dimensions Empathy of nursing staff and Assurance impact

positively on both Loyalty and Cumulative satisfaction.

The customer satisfaction dimensions Satisfaction with meals, Satisfaction with the nursing staff and

Satisfaction with fees all impact positively on both Loyalty and Cumulative satisfaction

*To whom all correspondence should be addressed.

Introduction

Every marketing textbook exhorts marketers to differentiate

themselves from competitors and competing brands (Lamb,

Hair, McDaniel, Boshoff & Terblanche, 2004). The

suggested differentiating variables range from branding to

convenience to price differentiation. However, many if not

most firms operate in markets where competing firms have

very similar cost structures which make price competition

difficult.

As most of the differentiating variables suggested in the

literature are easily copied by competitors, many firms are

focusing their efforts on quality of customer service as a

means of differentiation. Providing quality that meets or

exceeds customer expectations has become a major source

of competitive advantage for many firms as it reduces price

elasticities and builds loyalty and customer retention

(Anderson & Fornell, 1994:242). Service quality has also

been shown to be an important driver of customer

satisfaction both from a theoretical viewpoint (Heskett,

Sasser & Schlesinger, 1997) and empirically substantiated in

a variety of industries (Anderson & Sullivan, 1993;

Churchill & Suprenant, 1982) including service industries

such as tourism (Green & Boshoff, 2003) and health care

(Woodside, Frey & Daly, 1989).

The empirical findings of studies investigating the

relationships between service quality, customer satisfaction

and their outcomes have found broad support (Loveman,

1998: 18-31; Anderson & Mittal, 2000) for the relationships

described in the Service-Profit Chain suggested by Heskett,

Sasser and Schlesinger (1997). These relationships have,

however, not been considered in the South African private

hospital industry. This study thus attempts to assess what

dimensions of both customer satisfaction and service quality

drive ‘overall satisfaction’ and loyalty in the South African

private hospital industry.

Service quality

The first attempt to describe and define service quality was

the paradigm suggested by Grönroos (1983) who

distinguished between technical quality (what is done) and

functional quality (how it is done). The early work of

Grönroos (1983) was later extended by Parasuraman,

Zeithaml and Berry (1985:42). They argued that to fully

understand service quality, the intangible, heterogeneous

and inseparable nature of services must be acknowledged

and that service quality can be defined as the consumer’s

overall impression of the relative inferiority/superiority of

the organisation and its services (Bitner & Hubbert, 1994) or

as the customer's assessment of the overall excellence or

superiority of the service (Zeithaml, 1988). In these terms

service quality means conforming to customer expectations

(Lewis & Booms, 1983) and implies, from a consumer

perspective, the comparison of customer expectations with

customer perceptions of actual service performance

(Parasuraman et al., 1985).

28 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)

The concept of customer satisfaction

In the service environment, one customer satisfaction-

related debate is of particular importance, namely whether

customer satisfaction is an outcome or a process (Yi,

1991:69). To date there seems to be two schools of thought.

Churchill and Suprenant (1982) and Oliver (1989), on the

one hand, view customer satisfaction as an outcome

resulting from the consumption experience. To Hunt

(1977:455), on the other hand, satisfaction is not the

pleasure of the experience, it is the evaluation rendered that

the experience was at least as good as it was supposed to be.

The ‘satisfaction as a process’ school stresses that

satisfaction or dissatisfaction is not inherent in the product

but, instead, is the individual’s perceptions of that product’s

attributes as they relate to that individual. Thus, satisfaction

is idiosyncratic and, as a construct, is formed by the

interaction of perceptual interpretations of the service and

consumer expectations of that service. As a consequence,

different consumers will have varying levels of satisfaction

for an experience which is essentially the same.

Although both schools of thought (satisfaction as an

outcome and as a process) have been widely recognised, the

process-oriented approach seems more appropriate in the

service environment given that consumption is an

experience and consists of collective perceptual, evaluative

and psychological processes that combine to generate

consumer satisfaction. In addition, the nature of services

(eg, intangibility) and the peculiarities of marketing services

(eg, inseparability) necessitate a distinction between

‘overall’ or cumulative satisfaction and satisfaction with a

specific service encounter (transaction-specific satisfaction),

an important distinction which is often ignored (Bitner &

Hubbert, 1994; Voss & Parasuraman, 1995).

From an encounter-specific perspective, satisfaction is

viewed as a post-choice evaluative judgement of a specific

purchase occasion. Most behavioural research can be

interpreted as focusing on this conceptualisation. This

perspective is insufficient to explain customer satisfaction

for, as Bitner and Hubbert (1994) point out, the evaluation

of each encounter will not necessarily correlate with the

customer’s overall satisfaction with the firm or perceptions

of the firm’s quality. Over time, however, it is likely that

multiple service encounters will lead to an overall level of

satisfaction.

More recently, research has focused on satisfaction at a

more general or organisational level. From this brand-

specific perspective, satisfaction is an overall evaluation

based on many transient experiences with a good or service

over time and, as such, satisfaction can also be thought of as

an ongoing evaluation of a firm’s ability to deliver the

benefits a customer is seeking. Bitner and Hubbert (1994)

point out that overall satisfaction is likely to be

multidimensional and based on all encounters and

experiences with that particular service firm. These multiple

encounters may include several interactions with one person

as well as experiences with multiple contact persons in the

same firm (Oliva, Oliver & MacMillan, 1992). Thus,

transactional satisfaction can be considered a contributor

and subsequent modifier to a less dynamic attitude of

satisfaction at an organisational level, while overall

satisfaction can be considered as the customer’s global

evaluation of the product/service offering.

No matter how we perceive customer satisfaction, however,

there can be no doubt that it is the key to profitability

(maybe not the only one, admittedly) over the long term

(Oliver, 1997: 10) also in a hospital environment (Raju &

Lonial, 2001:140-154).

Loyalty

Some commentators, somewhat cynically, suggest that there

are just two types of consumers, namely those who are

intrinsically loyal to a brand or store and those potential

switchers who, on every purchase occasion again choose

between competing offerings (Colombo & Morrison, 1989).

Keeping customers loyal is not easy, but its importance can

hardly be overstated. In fact, consumer loyalty has been

described as the marketplace currency for the twenty-first

century (Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000).

Customer loyalty has been defined in various ways, from a

probability of repurchase to proportion of purchase (Sivadas

& Baker-Prewitt, 2000). At a general level, customer loyalty

is a positive propensity toward a store or brand (East,

Hammond, Harris & Lomax, 2000). A critical review of the

many definitions of loyalty suggests that loyalty is both a

cognitive construct (attitude) and a shopping behaviour

(Dick & Basu, 1994; Mellens, Dekimpe & Steenkamp,

1996).

Whilst loyalty in a health care and particularly a hospital

environment differs from brand or store loyalty (it is often

the physician who makes the choice or strongly influences

the choice of a hospital) there can be no doubt that the same

benefits of loyalty accrue to a hospital as would to a retailer

or bank, for instance.

No matter what the industry under discussion, loyal

customers are a competitive asset to any business

organisation (Dekimpe, Steenkamp, Mellens & Vanden

Abeele, 1997) as customer loyalty serves as a barrier to

competitive entry (Aaker, 1991) and thus, by implication, is

also a key determinant in predicting market share (Baldinger

& Rubinson, 1997; Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978) and

profitability (Reichheld, 1996).

The antecedents of loyalty

A review of the literature reveals numerous studies that have

reported a positive relationship between satisfaction and

measures of repurchase intentions (Bloemer & De Ruyter,

1998; Loveman, 1998; Jones, Mothersbaugh, & Beatty,

2000) and between positive service quality perceptions and

loyalty.

The South African health care sector

A fairly ‘pure’ service sector such as the health care sector

can be quite varied, especially with the inclusion of the

many ancillary services. Traditionally, the South African

health care sector has consisted of two industries, namely,

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 29

private hospitals and public hospitals. Recently, a major

development in the hospital environment has been the

emergence of public/private partnership hospitals (Wilson,

2002:90). Public hospitals are by far the larger industry. In

contrast, private hospitals, the majority of which are

Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA) members,

make up approximately one third of South Africa’ s

hospitals.

The private hospital industry

There are about 178 private hospitals in South Africa. Three

groups, namely Netcare, Afrox Health care Limited and

Medi-Clinic currently dominate South Africa’s private

hospital industry. The independents and smaller groups

comprise Clinix, Community Health, Curamed, Joint

Medical Holdings, Melomed and the Protector Group. The

three major players collectively own 80% of hospital beds in

the private health care industry (Bhoola, 2002:55).

The South African private health care market is an

increasingly competitive environment. Private hospitals in

particular compete aggressively to attract patients. As in any

other competitive environment competing hospitals have to

differentiate themselves in the minds of consumers and ensure

that their patients leave satisfied so as to ensure that they return

again and in this way ensure the hospital’s long-term survival.

Objectives

The objective of the study was to investigate whether, if a

private hospital can differentiate itself by means of superior

service quality and superior transaction-specific customer

satisfaction, it will be able to enhance loyalty (as measured

by purchasing intentions) among its patients. More

specifically, an attempt was made to assess which

dimensions of service quality and transaction-specific

customer satisfaction exert the strongest influence on two

dependent variables, namely loyalty (as measured by

intentions to repurchase) and customer satisfaction, the latter

measured as ‘overall’ or cumulative satisfaction (Johnson,

Anderson & Fornell, 1995).

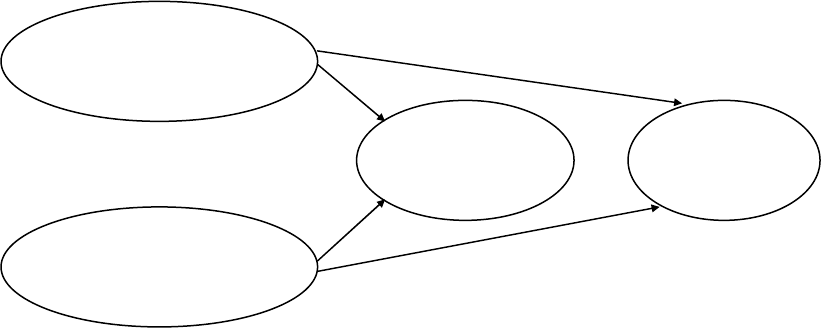

Figure 1 suggests that meeting consumer needs at the

attribute level will enhance cumulative customer satisfaction

which will in turn enhance loyalty/buying intentions and by

implication profitability as predicted by the Satisfaction-

Profit chain (Anderson & Mittal 2000:107-120).

Figure 1: The hypothesised relationships

Hypotheses

To assess the theoretical model depicted in Figure 1 the

following hypotheses were considered:

H

1

There is a positive relationship between perceived

service quality at the dimensional level and loyalty as

measured by buying intentions

H

2

There is a positive relationship between perceived

service quality at the dimensional level and cumulative

customer satisfaction

H

3

There is a positive relationship between customer

satisfaction at the dimensional level and loyalty as

measured by buying intentions

H

4

There is a positive relationship between customer

satisfaction at the dimensional level and cumulative

customer satisfaction

The research design

The measures

The best-known method of operationalising service quality

is the Gaps Model/SERVQUAL approach suggested by

Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry (1988). It is based on the

‘expectancy disconfirmation’ paradigm and measures

service quality perceptions (as opposed to so-called

‘objective’ quality) by comparing customer expectations

with the service performance.

During the initial operationalisation, model development

and scale development processes Parasuraman, Zeithaml

and Berry (1985) suggested that service quality consists of

10 dimensions, namely tangibles, reliability, responsiveness,

competence, courtesy, credibility, security, access,

communication and understanding the customer. This was

H

3

H

4

H

2

H

1

Perceived service

quality – dimensional level

Customer satisfaction -

dimensional level

Cumulative

customer

satisfaction

Loyalty –

buying

intentions

30 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)

later reduced to just five dimensions, namely reliability,

assurance, responsiveness, empathy and tangibles.

To overcome at least some of the problems associated with

the use of SERVQUAL (Cronin & Taylor, 1992) service

quality was measured along the original 10 dimensions as

service quality is a stronger predictor of customer

satisfaction (Green & Boshoff, 2003) than the later 5-factor

configuration.

The SERVQUAL instrument has been subjected to a fair

amount of criticism for its poor validity. Such criticisms

include paradigmatic problems, questions about its

dimensionality and particularly its poor predictive validity

(Buttle, 1995). The problem is that at this moment there is

no credible alternative to SERVQUAL to measure service

quality. The original version of SERVQUAL, which

measures ten instead of five dimensions, was utilised in this

study (Zeithaml, Parasuraman & Berry, 1990:21-22) to

measure service quality.

Customer satisfaction with the actual hospital experience (at

the dimensional level) was measured with 53 statements

based on a thorough literature review (Woodside et al.,

1989; Jun, Peterson & Zsidisin, 1998; Reidenbach &

Sandifer-Smallwood, 1990), as well as on the exploratory

study that preceded the empirical survey. Cumulative (or

overall) satisfaction, a global assessment as opposed to a

dimensional assessment, was used as dependent variable as

it has been shown to be a better predictor of loyalty (Olsen

& Johnson, 2003:194). Cumulative satisfaction was

measured with the following three semantic differentially-

scaled items:

Overall, how satisfied were you with your stay at

….? (satisfied ´ dissatisfied)

How would you rate the overall standard of service

at …? (excellent ´ poor)

Did you comment on any aspect of your hospital

stay to any hospital staff member (praised ´

complained)

Because one cannot refer to loyalty in the private hospital

industry in the same manner as say, in a retail context (due to

the way the buying decision is made), buying intentions were

used as a surrogate measure of loyalty. Buying intentions have

successfully been used as a surrogate for loyalty in a service

environment before (Shaw-Ching, Furrer & Sudharshan,

2001). The dependent variable in this study was thus measured

using the following five items:

I would not mind returning to …. again in the

future

I would recommend this hospital to family and

friends

In an emergency this is the hospital I would like to

be admitted to …

I regard myself as a ‘loyal’ customer of …

I would definitely return to this hospital in the

future if necessary

All items were linked to a 7-point Likert scale ranging from

Strongly Agree (7) to Strongly Disagree (1).

The sample

The sampling procedure can be described as a combination of

convenience and random sampling. The hospitals that

participated in this study were selected on a convenience basis.

Questionnaires were distributed on a random basis to patients

who booked into four hospitals belonging to one private

hospital group. One hospital in Cape Town, Port Elizabeth,

Durban and two in Johannesburg participated in the study. To

qualify to participate in the study respondents had to be over

the age of 20 years; had to be there to undergo an operation

(anaesthetic included); and had to have at least one overnight

stay in a hospital ward.

In total 3 800 questionnaires were distributed of which 425

were returned and 323 (or 11,2%) could be statistically

analysed.

The questionnaire was a self-administered questionnaire. It

was accompanied by a covering letter and information on an

incentive to complete the questionnaire, as well as a reply-

paid envelope. The questionnaires could be handed in before

patients left the hospital or else mailed back once they had

returned home.

Data analyses

The data were analysed in three phases. During the first

phase the discriminant validity of the instruments used to

measure cumulative customer satisfaction and

loyalty/willingness to re-purchase was subjected to an

exploratory factor analysis. Once a clear factor structure

emerged, the internal reliability of each factor was assessed

using Cronbach’s Alpha. The factors that emerged after the

exploratory factor analysis phase were then used as

independent variables in four subsequent multiple regression

analyses to assess the relationships predicted by the four

hypotheses and graphically depicted in Figure 1.

The empirical results

Discriminant validity

To assess the discriminant validity of the instruments used

to measure both service quality and customer satisfaction,

the remaining items were subjected to an exploratory factor

analysis using the computer programme BMDP4M (Frane,

Jennrich & Sampson, 1990) by specifying a Maximum

Likelihood and a Direct Quartimin oblique rotation

(Jennrich & Sampson, 1966) of the original factor matrix.

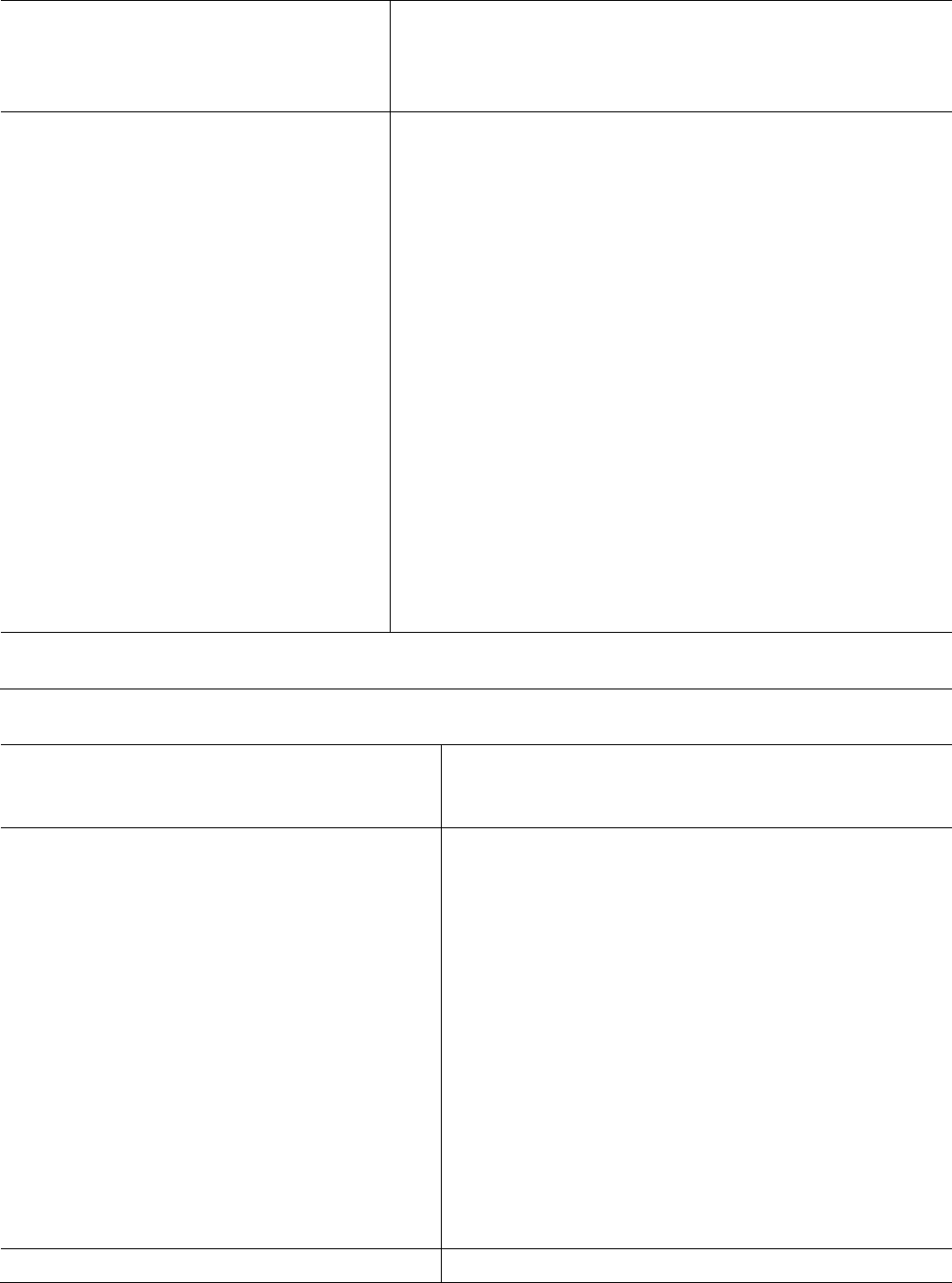

A variety of different exploratory factor analysis solutions

were considered. The results revealed, however, that neither

the ten dimensions nor the five dimensions of service quality

proposed by Parasuraman et al., (1988), could be replicated.

The most interpretable factor structure was the one shown in

Table 1. A number of items did not demonstrate sufficient

discriminant validity by either cross-loading or not loading

to a significant extent and were then deleted. Table 1 shows

that the service quality items used from the initial

SERVQUAL loaded on seven distinct factors, namely

Communication (measured by three items), Credibility

(measured by four items), Tangibles (measured by five

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 31

items), Understanding (measured by six items),

Responsiveness (measured by four items), Security

(measured by two items) and Doctor’s responsiveness

(measured by two items).

These dimensions were operationalised as follows:

Communication the patient receiving

information about his condition,

treatment, procedures to be

conducted and post-discharge

treatment/care

Tangibles perceptions of the cleanliness of

the hospital in general and the

wards in particular, the neatness

of the buildings, the décor in the

wards and the appearance of the

nursing staff

Empathy of nursing staff the responsiveness of the

nursing staff, their

understanding, the adequacy

and individualisation of

attention, efficiency and a

warm/caring attitude

Assurance hospital caring about its

patients, the hospital’s

reputation, patients’ confidence

in the hospital and feeling safe

there

Responsiveness of

administrative staff speedy admission, efficient in

dealing with problems, sincerity

in solving problems, responsive

to requests

Security both inside and outside the

hospital

Physician responsiveness physicians attending to the

needs of patients and being

punctual in doing ward rounds

The items used to measure customer satisfaction were also

subjected to an exploratory factor analysis. The most

interpretable factor structure is the one reported in Table 2.

It shows customer satisfaction in a hospital consists of 7

dimensions, namely Satisfaction with meals (measured by

six items), Satisfaction with fees (measured by four items),

Satisfaction with the nursing staff (measured by four items),

Satisfaction with the admission process (measured by three

items), Satisfaction with the theatre experience (measured

by four items), Satisfaction with the TV service in the wards

(measured by two items) and Satisfaction with the ward

arrival (measured by two items).

The underlying dimensions of customer satisfaction were

operationalised as:

Meals being tasty, nutritious,

attractively presented and at

correct temperatures and

adequate variety

Fees that are reasonable, worth the

money, value for money and not

expensive

Nursing staff that are cheerful, responsive,

kind/caring and adequately

skilled

Admission courteous/helpful, prepared to

listen, prompt admission

Theatre experience receiving pre-med in time,

proper preparation for

operation, easing of fears,

explanation by anaesthetist

TV service in ward access to a TV that is

functioning properly

Ward arrival being told what to do and where

ward facilities are

Internal reliability

The next phase of the data analysis was to assess the internal

reliability of the instrument used to test the variables in the

theoretical model depicted in Figure 1. This was done by

calculating Cronbach Alpha coefficients using the computer

programme SAS (SAS Institute, 1990).

Tables 1 and 2 show that all of the instruments used returned

initial Cronbach Alpha coefficients above the 0.7 threshold

recommended by Nunnally (1978) and Peterson (1994).

Tables 1 and 2 thus confirm the reliability, the discriminant

and the construct validity of the instruments used to measure

the independent variables used in the subsequent multiple

regression analyses.

The regression analyses results

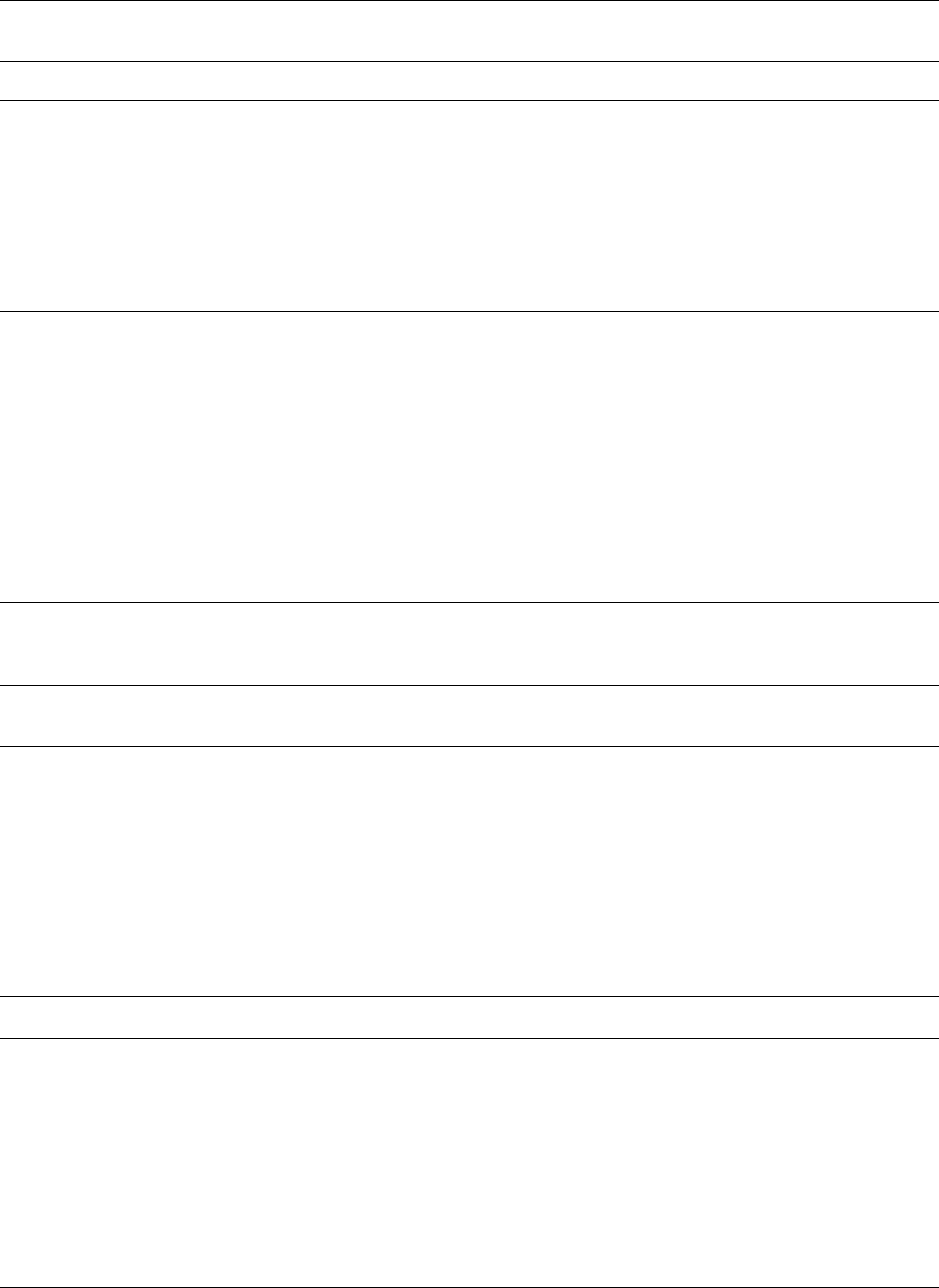

Table 3 shows that the service quality dimensions Empathy

of nursing staff (p < 0,001), Assurance (p < 0,001) and

Tangibles (p < 0,01) impact positively on Loyalty as

hypothesised. The impact of Security (p < 0,05) on Loyalty

is, however, negative. Hypothesis 1 is thus accepted in terms

of these four dimensions but rejected in respect of

Communication, Responsiveness and Physician

responsiveness.

32 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)

Table 1: Exploratory factor analysis results rix for service quality items

Service Quality Dimensions

Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6 Factor 7

Commu-

nication

Tangibles Empathy

of

nursing

staff

Assurance Respons-

iveness

Security Physician

responsive-

ness

Patients assured of receiving adequate information about their

condition

0,945

Patients assured of receiving adequate information about their

treatment

0,890

Procedures thoroughly explained to patients 0,745

Discharge care thoroughly explained 0,546

Spotlessly clean wards at ___ 0,866

___ is a clean hospital 0,801

___ maintains a neat appearance of buildings 0,602

Tastefully decorated wards 0,552

Nursing staff look professional and neat in their uniforms 0,522

Service at ___ is excellent overall 0,444

Nurses never too busy to respond to patients’ needs 0,699

Nurses show understanding toward patients’ feelings of discomfort 0,644

Patients do not feel neglected by nursing staff 0,610

Patients are given plenty of individual attention 0,607

Nursing staff efficient at dealing with patients’ problems 0,421

Nurses show understanding when patients feel low 0,490

Nurses treat patients with a warm and caring attitude 0,493

___ cares about its patients 0,815

Patients feel safe at ___ hospital 0,796

___ has an excellent reputation 0,701

Patients can feel confident in treatment to be received 0,630

Administrative staff efficient at dealing with patients’

queries/problems

0,827

Admission handled quickly and efficiently by administrative staff 0,696

Administrative staff sincerely interested in solving patients’

problems

0,637

Administrative staff never too busy to respond to patients’ requests 0,630

Adequate security provided inside hospital 0,788

Adequate security provided outside hospital 0,754

Doctors are punctual when conducting ward rounds 0,723

Doctors can be counted on to attend to their patients’ needs 0,540

Eigen values: 15,45 1,74 1,47 1,33 1,07 0,90 0,89

Cronbach’s alpha: 0,92 0,88 0,95 0,95 0,87 0,82 0,77

Table 2: Factor matrix for customer satisfaction items

Customer Satisfaction Dimensions

Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3 Factor 4 Factor 5 Factor 6

Factor7

Meals Fees Nursing

Staff

Admission Theatre TV’s in

Wards

Ward

Arrival

Meals were tasty 0,987

Meals were nutritious 0,903

Meals were attractively presented 0,899

Overall, patient enjoyed the food while at ___ 0,876

Meals always served at correct temperature 0,715

Meals were served in a variety of ways 0,640

Fees at ___ are reasonable 0,880

Considering fees charged, stay worth the money 0,779

A stay at ___ is good value for money 0,773

___’s fees are not expensive 0,618

Nursing staff were always cheerful 0,888

Nursing staff responded promptly to patient’s needs 0,839

Nursing staff kind and caring throughout patient’s stay 0,706

Nursing staff were skilled in administering procedures 0,583

Administrative staff courteous and helpful at admissions counter 0,825

Administrative staff willing to listen to patient’s concerns 0,675

Patient’s admittance procedure carried out promptly 0,634

Pre-med (for surgery) was administered at correct time 0,824

Preparation for surgery carried out efficiently 0,569

Nursing staff eased patient’s fears about the surgery 0,517

Anaesthetist came to explain his role during surgery 0,403

Television sets functioned properly 0,993

Television set in the ward 0,671

Upon arrival in ward, nursing staff told patient what to do next

0,561

After arrival in ward, patient shown ablution/ward facilities

0,471

Eigen values: 9,76 2,91 1,69 1,44 1,28 1,20

0,84

Cronbach’s alpha: 0,94 0,89 0,91 0,79 0,77 0,80

0,77

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 33

Table 3 thus shows that the more patients perceive the

nursing staff as empathetic, feel assured and safe in the

hospital, and evaluate the physical environment (Tangibles)

positively, the more likely they are to remain loyal to the

hospital. In the case of Security, however, the relationship is

negative. In other words, too much security will reduce

Loyalty.

Table 3 reveals that the modelled independent variables

(service quality dimensions) explain 58,5% of the variation

in the dependent variable (Loyalty).

According to Table 4 only two service quality dimensions

namely Empathy of nursing staff (p < 0,001) and Assurance

(p < 0,001), impact positively on Cumulative satisfaction as

suggested by hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 2 is thus accepted in

terms of Empathy of nursing staff and Assurance but

rejected in respect of Communication, Tangibles,

Responsiveness, Security and Physician responsiveness.

Table 4 reveals that the modelled independent variables

(service quality dimensions) explain 60,3% of the variation

in the dependent variable (Loyalty).

When individual dimensions of customer satisfaction are

regressed on Loyalty, Table 5 shows that Satisfaction with

meals (p < 0,001), Satisfaction with the nursing staff (p <

0,001), Satisfaction with fees (p < 0,01) and Satisfaction

with the television service (p < 0,01) all impact positively on

Loyalty. Hypothesis H3 is thus accepted in terms of these

four dimensions but rejected in terms of Satisfaction with

admission, Satisfaction with ward arrival and Satisfaction

with the Theatre experience (p > 0,05).

Table 5 also shows that the strongest predictor of

Cumulative satisfaction is Satisfaction with the nursing staff

(estimate 0,386) and that the six dimensions of Cumulative

satisfaction included in the regression model explain 68,3%

of the variation in the dependent variable (Loyalty).

To assess the last hypothesis the impact of the individual

customer satisfaction dimensions on Cumulative satisfaction

(an “overall” assessment) was assessed. Table 6 shows that

Satisfaction with nursing staff (p < 0,001), Satisfaction with

fees (p < 0,001) and Satisfaction with meals (p < 0,01), all

exert a positive influence on Cumulative satisfaction as

suggested by H1 which is thus accepted. However, the

hypothesis is rejected in respect of Satisfaction with

administration, Satisfaction with Arrival, Satisfaction with

the theatre experience and Satisfaction with the TV service.

Table 6 also shows that Satisfaction with the nursing staff is

the strongest predictor of Cumulative satisfaction and that

66,0% of the variation in the dependent variable (Loyalty) is

explained by the seven independent variables (satisfaction

dimensions).

Managerial implications

If a private hospital sets itself the goal of enhancing loyalty

of its patients, it is clear from Table 3 that service quality

efforts will have to be focused on the Empathetic behaviour

of its nursing staff and conveying a sense of Assurance.

Nursing training will thus have to move beyond normal

nursing skills, competencies and efficiency to also

emphasise ‘softer’ skills such the responsiveness of the

nursing staff, their understanding of patients’ concerns and

fears, providing individualised attention and developing the

ability to demonstrate a warm/caring attitude towards

patients. To convey a sense of Assurance, on the other hand,

the hospital will have to cultivate a perception that will be

based on more than just interaction with the nursing staff.

During the whole hospitalisation experience and at each

‘contact point’ all employees should demonstrate that they

care about its patients, are careful in protecting and

enhancing the hospital’s reputation, do everything to gain

the patients’ confidence in the hospital and ensure that

patients feel safe during their hospitalisation. Table 4 shows

that careful management of the Empathy of the nursing staff

and of feelings of Assurance will not only enhance patient

Loyalty but will also enhance patients’ ratings of their

overall or cumulative satisfaction.

Another dimension that impacts on patient Loyalty (which can

be described as a ‘hard issue’) is Tangibles. Tangibles are a

service quality dimension that has proved relatively

unimportant in many service quality studies (Zeithaml et al.,

1990:29). It is obviously different in the hospital environment.

Perceptions of the cleanliness of the hospital in general and the

wards in particular, the neatness of the buildings, the décor in

the wards and the appearance of the nursing staff will all

influence whether a patient will return to a hospital or not.

Tangibles are typically the easiest service quality dimension to

manage and manipulate as they do not involve people.

The fourth service quality dimension to impact on Loyalty is

Security (see Table 4). In other words, it appears as if a too

strong security presence (too many and/or heavily armed

security guards, inappropriate security fencing etc) can

actually raise concerns and scare-off patients, and will

reduce their intentions to again patronise the hospital.

Security arrangements must thus be implemented very

discreetly and care taken not to overdo the installation of

visible security measures.

Perceptions of loyalty can also be enhanced by ensuring

satisfaction with transaction-specific dimensions of the

service rendered. Table 5 shows that customer satisfaction

with the meals provided, satisfaction with the nursing staff,

satisfaction with the fees paid and satisfaction with the TV

service in the wards will encourage patients to return to the

hospital in the future. In other words, tasty, attractive,

nutritious meals combined with variety will make patients

want to come back. Table 5 underlines the critically

important role that the nursing staff play in all facets of

patients’ evaluation. If patients experience the nursing staff

as cheerful, kind, caring, courteous as well as highly skilled

and prompt, they are significantly more likely to return to

the same hospital should the need arise.

34 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)

Table 3: Multiple regression results: Impact of service quality dimensions on loyalty

Dependent Variable: LOYALTY (Buying intentions or willingness to re-purchase)

Sum of Mean

Source DF Squares Square F value Pr > F

Model 7 2013,39 287,63 63,56 0,0001

Error 315 1425,56 4,53

Corrected Total 322 3438,95

R

2

C.V. Root MSE Loyalty Mean

58,5% 11,92 2,13 17,84

Exceedance Std Error

Parameter Estimate T-value probability of estimate

INTERCEPT 2,024 2,04 0,0418 0,990

COMMUNICATION 0,048 1,16 0,2478 0,041

EMPATHY: NURSING STAFF 0,160 5,81 0,0001*** 0,028

TANGIBLES 0,126 2,97 0,0032** 0,043

ASSURANCE 0,227 4,01 0,0001*** 0,057

RESPONSIVENESS: ADMIN 0,026 0,61 0,5440 0,043

SECURITY -0,147 -2,15 0,0323* 0,068

RESPONSIVENESS: PHYSICIAN -0,003 -0,04 0,9669 0,076

---------------------

*** = p < ,001

** = p < 0,01

* = p < 0,05

Table 4: Multiple regression results: Impact of service quality dimensions on cumulative satisfaction

Dependent Variable: CUMULATIVE SATISFACTION

Sum of Mean

Source DF Squares Square F value Pr > F

Model 7 6797,42 971,06 68,46 0,0001

Error 315 4467,76 4,18

Corrected Total 322 11265,18

R

2

C.V. Root MSE CUM SAT Mean

60,3% 12,37 3,77 30,43

Exceedance Std Error

Parameter Estimate T-value probability of estimate

INTERCEPT 1,512 0,86 0,3890 1,753

COMMUNICATION -0,082 -1,12 0,2651 0,073

EMPATHY: NURSING STAFF 0,274 5,64 0,0001*** 0,049

TANGIBLES 0,096 1,28 0,2028 0,075

ASSURANCE 0,653 6,51 0,0001*** 0,100

RESPONSIVENESS: ADMIN 0,050 0,66 0,5110 0,076

SECURITY -0,050 -0,41 0,6806 0,121

RESPONSIVENESS: PHYSICIAN 0,028 0,21 0,8323 0,134

---------------------

*** = p < ,001

** = p < 0,01

* = p < 0,05

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 35

Table 5: Multiple regression results: Impact of satisfaction dimensions on loyalty

Dependent Variable: LOYALTY (Willingness to re-purchase)

Sum of Mean

Source DF Squares Square F value Pr > F

Model 7 2348,97 335,57 96,98 0,0001

Error 315 1089,98 3,460

Corrected Total 322 3438,95

R

2

C.V. Root MSE LOYALTY Mean

68.3% 10,43 1,86 17,84

Exceedance Std Error

Parameter Estimate T-value probability of estimate

INTERCEPT 2,0622 2,46 0,0143 0,837

MEALS 0,066 4,50 0,0001*** 0,015

NURSING STAFF 0,386 11,99 0,0001*** 0,032

FEES 0,080 2,77 0,0060** 0,029

ADMISSION 0,025 0,55 0,5852 0,046

WARD ARRIVAL 0,028 1,02 0,3067 0,027

THEATRE 0,020 0,63 0,5260 0,032

TV 0,129 2,67 0,0079** 0,048

---------------------

*** = p < ,001

** = p < 0,01

* = p < 0,05

Table 6: Multiple regression results: Impact of satisfaction dimensions on cumulative satisfaction

Dependent Variable: CUMULATIVE SATISFACTION

Sum of Mean

Source DF Squares Square F value Pr > F

Model 7 7439,27 1062,75 87,50 0,0001

Error 315 3825,92 12,15

Corrected Total 322 11265,18

R

2

C.V. Root MSE CUM SAT Mean

66.0% 11,45 3,485 30,430341

Exceedance Std Error

Parameter Estimate T-value probability of estimate

INTERCEPT 2,763 1,76 0,0790 1,568

MEALS 0,083 3,03 0,0026** 0,027

NURSING STAFF 0,664 11,00 0,0001*** 0,060

FEES 0,309 5,71 0,0001*** 0,054

ADMISSION -0,021 -0,24 0,8111 0,086

WARD ARRIVAL 0,0909 1,81 0,0715 0,050

THEATRE 0,0504 0,85 0,3936 0,059

TV 0,0714 0,79 0,4286 0,090

---------------------

*** = p < .001

** = p < 0.01

* = p < 0.05

36 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)

According to Table 5 patients are also more likely to return

to a hospital (loyalty) if they perceive the fees that they are

charged as fair, reasonable and good value for the money

paid (fees), and if, when they have access to a TV service in

the wards, this service functions effectively. Hospital

managers must thus ensure that patients are not overcharged,

that they receive an itemised account and even, when

necessary, provide a justification or an explanation for

exceptional charges. Furthermore, it appears as if patients

regard a functional TV service as ‘a given’ and care must be

taken to ensure that the service is always functional and that

a back-up TV or repair staff are available to ensure an

uninterrupted service.

Table 6 confirms that the same transaction-specific

dimensions also impact on Cumulative satisfaction, except

for the TV service. In other words, patients who report high

levels of satisfaction with the meals provided, satisfaction

with the nursing staff and satisfaction with the fees paid,

will besides remaining Loyal to the hospital, also report high

levels of satisfaction with the service encountered.

References

Aaker, D.A. 1991. ‘Measuring brand equity across products

and markets’, California Management Review, 38(2):102-

120.

Anderson, E.W. & Fornell, C. 1994. ‘A customer

satisfaction research prospectus’. In Rust, R.T. & Oliver,

R.L. (Eds.). Service quality: New directions in theory and

practice. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, pp.

241-268.

Anderson, E.W. & Mittal, V. 2000. ‘Strengthening the

satisfaction-profit chain’, Journal of Service Research,

3(2):107-120.

Anderson, E.W. & Sullivan, M.W. 1993. ‘The antecedents

and consequences of customer satisfaction for firms’,

Marketing Science, 12(2):25-143.

Baldinger, A.L. & Rubinson, J. 1997. ‘The jeopardy in

double jeopardy’, Journal of Advertising Research,

37(6):37-49.

Bhoola, R. 2002. Health Annals. Independent hospitals in

the private hospital industry. 11

th

Annual publication of the

Hospital Association of South Africa. Johannesburg: The

Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA).

Bitner, M.J. & Hubbert, A.R. 1994. ‘Encounter satisfaction

versus overall satisfaction versus quality: The customers

voice’. In Rust, R.T. & Oliver R.L. (Eds.). Service Quality:

New directions in theory and practice, Thousand Oaks,

California, Sage Publications, pp. 72-94,

Bloemer, J. & De Ruyter, K. 1998. ‘On the relationship

between store image, store satisfaction and store loyalty’,

European Journal of Marketing, 32(5/6): 499-513.

Buttle, F.A. 1995. ‘What future for SERVQUAL?’ In

Proceedings of the European Marketing Academy’s 24

th

Annual Conference, Paris, 16-19 May, pp.211-230.

Churchill, G.A. Jr. & Suprenant, C. 1982. ‘An investigation

into the determinants of customer satisfaction’, Journal of

Marketing Research, 19(4):491-504.

Colombo, R.A. & Morrison, D.G. 1989. ‘A brand switching

model with implications for marketing strategies’,

Marketing Science, 8(1):88-99.

Cronin, J.J. & Taylor, S.A. 1992. ‘Measuring service

quality: A re-examination and extention’, Journal of

Marketing, 56(3):55-68.

Dekimpe, M.G., Steenkamp, J.E.M., Mellens, M. & Van den

Abeele, P. 1997. ‘Decline and variability in brand loyalty’,

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14(5):405-

420.

Dick, A.S., & Basu, K. 1994. ‘Customer loyalty: Towards

an integrated framework,’ Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 22(2):99-113.

East, R., Hammond, K., Harris, P. & Lomax, W. 2000.

‘First-store loyalty and retention’, Journal of Marketing

Management:16, 307-325.

Frane, J., Jennrich, R.I., & Sampson, P.F. 1990. ‘P4M

Factor Analysis’. In Dixon, W.J. & Brown, M.B. (Eds.).

BMDP Statistical Software Manual, Vol 1. Berkeley:

University of California, Berkeley, pp. 311-337.

Green, S. & Boshoff, C. 2003. ‘An empirical assessment of

the relationships between service quality, satisfaction and

value: A tourism study,’ Management Dynamics, 11(3):1-

16.

Grönroos, C. 1983. ‘Innovative marketing strategies and

organization structures for service firms’. In Berry, L.L.,

Shostack, G.L. & Upah, G.D. (Eds.). Emerging perspectives

on services marketing. Chicago, Ill.: American Marketing

Association.

Heskett, J., Sasser, W. & Schlesinger, L. 1997. The service-

profit chain. New York: The Free Press.

Hunt, H.K. 1977. ‘CS/D - Overview and future research

directions’. In Hunt, H.K. (Ed.). Conceptualisation and

measurement of customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

Cambridge, MA: Marketing Science Institute, pp. 455-488.

Jacoby, J. & Chestnut, R.W. 1978. Brand loyalty

measurement and management. New York : Wiley.

Jennrich, R.I. & Sampson, P.F. 1966. ‘Rotation for simple

loadings’, Psychometrica, 31:313-323.

Jones, M.A., Mothersbaugh, D.L., & Beatty, S.E. 2000.

‘Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services’,

Journal of Retailing, 76(2): 259–274.

S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4) 37

Johnson, M.D. Anderson, E.W. & Fornell, C. 1995.

‘Rational and adaptive performance expectations in a

customer satisfaction framework’, Journal of Consumer

Research, 21:128-140.

Jun, M., Peterson, R.T. & Zsidisin, G.A. 1998. ‘The

identification and measurement of quality dimensions in

health care: Focus group interview results’, Health Care

Management Review, 23(4):81-96.

Lamb, C.W., Hair, J.F., McDaniel, C., Boshoff, C. &

Terblanche, N.S. 2004. Marketing. 2

nd

South African

Edition. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, R.C. & Booms, B.H. 1983. ‘The marketing aspects

of service quality’. In Berry, L.L., Shostack, G.L. & Upah,

G.D. (Eds.). Emerging perspectives on services marketing.

Chicago: American Marketing Association, pp. 99-107.

Loveman, G.W. 1998. ‘Employee satisfaction, customer

loyalty and financial performance: An empirical

examination of the service profit chain in retail banking’,

Journal of Service Research, 1(1):18-31.

Mellens, M., Dekimpe, M.G. & Steenkamp, J. E. M. 1996.

‘A review of brand-loyalty measures in marketing’,

Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, 41(4): 507-533.

Nunnally, J. 1978. Psychometric theory. 2nd Edition. New

York: Mc Graw-Hill.

Oliva, T.A., Oliver, R.L. & MacMillan, I.C. 1992. ‘A

catastrophe model for developing service satisfaction

strategies’, Journal of Marketing, 56(2):83-95.

Oliver, R.L. 1997. Customer satisfaction: A behavioral

perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Oliver, R.L. 1989. ‘Processing of the satisfaction response

in consumption: A suggested framework for research

propositions’, Journal of Consumer Satisfaction,

Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behaviour, 2:1-16.

Olsen, L.L. & Johnson, M.D. 2003. ‘Service equity,

satisfaction and loyalty: From transaction-specific to

cumulative evaluations’, Journal of Service Research,

5(3):184 – 195.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. 1985. ‘A

conceptual model of service quality and its implications for

future research’, Journal of Marketing, 49(4): 41-50.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. 1988.

‘SERVQUAL: A multi-item scale for measuring consumer

perceptions of service quality’, Journal of Retailing,

64(1):12-40.

Peterson, R.A. 1994. ‘A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s

coefficient alpha’, Journal of Consumer Research,

21(3):381-391.

Raju, P.S. & Lonial, S.C. 2001. ‘The impact of quality

context and market orientation on organizational

performance in a services environment’, Journal of Service

Research, 4(2):140-154.

Reichheld, F.F. 1996. The loyalty effect – the hidden force

behind growth, profits and lasting value. Boston, MA:

Harvard Business School Press.

Reidenbach, R.E. & Sandifer-Smallwood, B. 1990.

‘Exploring perceptions of hospital operations by a modified

SERVQUAL approach’, Journal of Health Care Marketing,

10(4):47-55.

SAS Institute Inc. 1990. SAS Procedures. Release 6.03

Edition. Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute.

Shaw-Ching, L.B., Furrer, O. & Sudharsan, D. 2001. ‘The

relationships between culture and behavioral intentions

toward services’, Journal of Service Research, 4(2): 118-

129.

Singh, J. & Sirdeshmukh, D. 2000. ‘Agency and trust

mechanisms in relational exchanges’, Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1):150-167.

Sivadas, E. & Baker-Prewitt, J.L. 2000. ‘An examination of

the relationship between service quality, customer

satisfaction, and store loyalty’, International Journal of

Retail & Distribution Management, 28(2):73-82.

Voss, G.B. & Parasuraman, A. 1995. Prepurchase

preference and postpurchase satisfaction in service

exchange. Working Paper, Marketing Science Institute,

Report Number 95-113, October.

Woodside, A.G., Frey, L.L. & Daly, R.T., 1989. ‘Linking

service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioural

intention’, Journal of Health care Marketing, 9(4):5-17.

Wilson, S. 2002. Health Annals. A new dawn in African

health care facilities management. 11

th

Annual publication

of the Hospital Association of South Africa. Johannesburg:

The Hospital Association of South Africa (HASA).

Yi, Y. 1991. ‘A critical review of customer satisfaction’. In

Zeithaml, V.A. (Ed.). Review of marketing 1990. Chicago:

American Marketing Association, pp. 68-123.

Zeithaml, V.A. 1988. ‘Consumer perceptions of price,

quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of

evidence’, Journal of Marketing, 52 (3):2-22.

Zeithaml, V.A., Parasuraman, A. & Berry, L.L. 1990.

Delivering quality service. New York: The Free Press.

38 S.Afr.J.Bus.Manage.2004,35(4)