Claes Fornell, Forrest V. Morgeson III, & G. Tomas M. Hult

Stock Returns on Customer

Satisfaction Do Beat the Market:

Gauging the Effect of a

Marketing Intangible

A debate about whether firms with superior customer satisfact ion earn superior stock returns has been persistent in the

literature. Using 15 years of audited returns, the authors find convincing empirical evidence that stock returns on

customer satisfaction do beat the market. The recorded cumulative returns were 518% over the years studied

(2000–2014), compared with a 31% increase for the S&P 500. Similar results using back-tested instead of real returns

were found in the United Kingdom. The effect of customer satisfaction on stock price is, at least in part, channeled

through earnings surprises. Consistent with theory, customer satisfaction has an effect on earnings themselves. In

addition, the authors examine the effect of stock returns from earnings on stock returns from customer satisfaction. If

earnings returns are included among the risk factors in the asset pricing model, the earnings variable partially mitigates

the returns on customer satisfaction. Because of the long time series, it is also possible to examine time periods when

customer satisfaction returns were below market. The reversal of the general trend largely resulted from short-term

market idiosyncrasies with little or no support from fundamentals. Such irregularities have been infrequent and

eventually self-correcting. The authors provide reasons why irregularities may occur from time to time.

Keywords: customer satisfaction, customer lifetime value, intangibles, stock portfolio returns, abnormal returns

A

mong the many potential performance outcomes for

marketing, there has been a rapid rise in interest in

measures of stock performance and customer sat-

isfaction over the past severa l years (e.g., Katsikeas et al.

2016). The literature on customer satisfaction and stock

returns has also become fairly extensive (Aksoy et al. 2008;

Anderson, Fornell, and Mazvancheryl 2004; Anderson and

Mansi 2009; Bell, Ledoit, and Wolf 2014; Fornell, Mithas,

and Morge son 2009a, b; Fornell et al. 2006; Gruca and Rego

2005; Ittner and Larcker 1998; Ittner, Larcker, and Taylor

2009; Jacobson and Mizik 2009a, b; Lambert 1998; Luo,

Homburg, and Wieseke 2010; Malshe and Agarwal 2015;

Ngobo, Casta, and Ramo nd 2012; O’Sullivan, Hutchinson,

and O’ Connell 2009; O’Sullivan and McCallig 2009; Peng

et al. 2014; Tuli and Bha radwaj 2009). Although most of

these studies examine customer satisfaction using the same

data source (American Customer Satisfaction Index [ACSI];

www.theacsi.org) and find predominantly positive risk-

adjusted stock returns, their conclusions differ with respect

to the statistical signi ficance of the abnormal returns and

whether there is evidence of mispricing.

Some researchers (Bell, Ledoit, and Wolf 2014; Jacobson

and Mizik 2009a; O’Sullivan, Hutchinson, and O’Connell

2009) have argued that abnormal returns cannot be dis-

tinguished from random variation, or that there is no evidence

that customer satisfaction predicts long-term stock returns

(Ittner, Larcker, and Taylor 2009). These arguments and pre-

dictions can now be put to the test. If they are correct, then

customer satisfaction returns subsequent to these cited studies

should approximately equal market returns. The new empirical

evidence, however, points to anything but equal to market

returns. For the full 15-year time period (2000–2014), the

model-free audited cumulative gross returns on customer sat-

isfaction amounted to 518%.

1

By comparison, the Standard

& Poor’s [S&P] 500 grew by 31% over the same period

(2000–2014). On an annual basis, the customer satisfaction

portfolio outperformed the S&P in 14 out of 15 years. The

magnitude of such a return disparity over a period of 15 years

Claes Fornell is Chairman, CFI Group (e-mail: cfornell@cfigroup.com).

Forrest V. Morgeson III is Director of Research, American Customer

Satisfaction Index, LLC (e-mail: morgeson@theacsi.org). G. Tomas M. Hult

is Professor and Byington Endowed Chair, Eli Broad College of Business,

the input, feedback, and assistance provided by Joshua Blechman,

Xueming Luo, and David Durfee.

1

The lead author is the owner and founder of the U.S. fund studied

and the American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI). As regis-

tered under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, the fund ’s

investment manager is regulated by the SEC. This should not be

taken to imply a certain level of skill or training. The returns were

audited by an independent third-party accounting firm, unaffiliated

with the authors and registered with the Public Company

Accounting Oversight Board. The audited returns have also been

provided to the Editor in Chief as a part of the review process.

© 2016, American Marketing Assoc iation Journal of Marketing

ISSN: 0022-2429 (print) Vol. 80 (September 2016), 92–107

1547-7185 (electronic) DOI: 10.1509/jm.15.022992

implies that known risk factors or sector biases are very unlikely

explanations because investors would have had enough time to

discover the anomalies and adjust to them accordingly.

These findings do not mean, however, that the returns

cannot be mitigated by known factors from time to time. In-

deed, we find that this is the case. Moreover, and similar to

the impact of employee satisfaction on stock prices (Edmans

2011), there is evidence that the effect of customer satisfaction

is channeled, at least to some extent, through earnings surprises.

That is, to the extent that the market does not react to news

about customer satisfaction, there is a reaction to its materi-

alization in corporate earnings and effect on earnings surprises.

We find significant relationships between customer satisfac-

tion and earnings and that customer satisfaction is predictive of

earnings surprises. In turn, stock returns on earnings mitigate

the effect on customer satisfaction returns. That is, some of the

effect on stock prices from customer satisfaction seems to be

absorbed by the effect of earnings on stock prices.

In addition, we identify time periods under which the

abnormal returns are negative (even though the absolute re-

turns remain positive), but they are too short in duration to be

statistically significant and are overwhelmed by the predom-

inance of positive risk-adjusted alphas. Nevertheless, there

are lessons to be learned from the return reversals. They seem

to happen largely without assistance from a corresponding

reversal in fundamentals but as a reaction to price increases of

hitherto strong performing stocks in favor of less expensive

stocks (i.e., stocks with lower price-to-earnings [P/E] ratios).

The remainder of the study is structured as follows. We

begin with the theoretical impetus behind the proposition that

customer satisfaction is germane to firm value and demon-

strate how a small increase in customer retention can have a

large effect on equity value. This is of critical importance

because the equity value grows exponentially at higher levels

of customer retention, whereas the value of an increase in

customer retention from a low level to a somewha t higher

level is much smaller. The implication, which we test in this

study, is that changes in customer satisfaction are much more

likely to have an effect when they are accompanied by high

levels of customer satisfaction.

Next, we present the data from the ACSI and the stock

portfolio. We describe the relevant properties of each—the

ACSI, with respect to the degree to which it is representative

of the U.S. stock market (S&P 500 index), and the stock

portfolio, with respect to how it is constructed wi th ACSI data

as input. In both cases, we take these data sets as they are. The

same is true with respect to the U.K. customer satisfaction data,

but not the U.K. portfolio returns. The U.K. portfolio returns

result from back testing that we performed. Because of the low

credibility of back testing due to the risk of data snooping (Lo

and MacKinlay 1990), we selected the simplest and most

transparent of trading rules, as we detail subsequently.

Following this, we turn to the analyses and findings. We

employ the standard capital asset pricing model (CAPM) to

estimate the market risk premium and add the momentum

risk premium (Carhart 1997), the size risk prem ium, and the

growth risk premium (Fama and French 1993). The Barra

model, controlled for market returns, is used for additional

attribution analysis and shows that only 2 (technology and

retail) out of 16 style factors have a significant effect, and

approximately 80% of the return variance is due to idio-

syncratic effects. Next , we estimate the effect of customer

satisfaction on earnings and earnings surprises as well as the

effect of earnings returns on customer satisfaction returns.

We find that customer satisfaction has a signi ficant effect on

both earnings and earnings surprises. As we hypothesize,

changes in customer satisfaction have an effect on earnings

only if they are complemented by high levels of customer

satisfaction. We also use the new five-factor Fama–French

(2015) model to estimate the effect of earnings returns on

customer satisfaction returns, finding that returns on earnings

reduce returns on customer satisfaction to some degree.

Finally, we examine the extent to which the returns to

customer satisfaction can be generalized. Confirmatory evidence

from the United Kingdom shows results similar to those in the

United States. There is also disconfirmatory evidence: over the

15-year time period, stocks of companies with strong customer

satisfaction did not always outperform the market. In particu-

lar, there was a time period in 2012–2013 marked by under-

performance. We examine market behavior during this period and

find that it deviates substantially from the norm in the sense that

companies that have weak balance sheets, are heavily shorted,

and have low price-to-earnings ratios outperformed the market.

Theoretical Impetus

Major shifts in economic activity over the past several decades

have caused intangible assets to become a major force for value

creation, economic growth, and performance assessment (e.g.,

Katsikeas et al. 2016). These assets loom large in the modern

economy and are often valued higher than the assets on balance

sheets. They are generally not, however, capitalized like other

investments, thereby disconnecting the timing of income from

expenditure in financial statements. For example, even though

the benefits accrue in the future, investments in customer service

are usually fully expensed when they occur. As a result, they

might become visible in income statements as an input variable

without much information about the nature or timing of actual

outputs. Under such circumstanc es, it is difficult to ascertain the

real value contribution from having satisfied customers. For-

tunately, there is output information available, but even so, the

economic value of customer satisfaction still might not become

manifest until there is an impact on other outputs (e.g., earnings).

Perhaps more than any other intangible, satisfied cus-

tomers are essential for any seller in a competitive market

if repeat business is a significant portion of total revenue.

Accordingly, customer satisfaction occupies a central place

in both micro and macro analysis. At the micro level, it is

a leading indicator of favorable (high level/low volatil ity)

net cash flows (e.g., Gruca and Rego 2005). At the macro level,

it is related to economic growth through consumer spend-

ing and to the efficiency by which capital is allocated (e.g.,

Fornell, Rust, and Dekimpe 2010). Allocative efficiency, in

this sense, depends on the joint ability of consumer and equity

markets to punish (reward) firms that fail (succeed) in sat-

isfying their customers. That is, consumer markets reward

high-consumer-utility-produ cing firms with repeat busi-

ness and punish low-consumer-utility-producing ones by

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 93

defection. By rewarding high-consumer-utility-producing

firms and their shareholders with higher stock prices an d

penalizing low-consumer-utility-producing firms with capital

withdrawal, capital markets would be in line with consumer

markets under the notion of allocative efficiency. It is in this

sense that buyer satisfaction plays a vital role in the individual

company’s ability to generate wealth at the micro level and in

allocative efficiency at the macro level.

Most consumer markets are characterized by numerous

purchase alternatives and by repeat sales as a large portion of

firm revenue. High customer satisfaction, relative to competi-

tion, is associated with repeat purchase, market share protec-

tion, lower price elasticity, lower transaction costs, and lower

selling/marketing costs (Anderson, Fornell, and Lehmann 1994).

Satisfied customers are therefore important for earnings, return

on investments, return on assets, and cash flows (Aksoy et al.

2008; Anderson, Fornell, and Mazvancheryl 2004; Fornell et al.

2006; Gruca and Rego 2005; Tuli and Bharadwaj 2009). Be-

cause of its influence on buyer loyalty, customer satisfaction is

also beneficial for risk reduction. Systematic, idiosyncratic, and

downside risk are lower for firmswithstrongcustomersat-

isfaction (Fornell, Mithas, and Morgeson 2009a, b; Tuli and

Bharadwaj 2009). In addition, customer satisfaction is asso-

ciated with other benefits, such as positive word of mouth,

higher reservation prices, more cross-buying, fewer consumer

complaints, lower warranty and field service costs, and less

customer defection and employee turnover (Fornell et al. 2006).

Most of these effects have positive impacts on acceleration,

stability, size, and—by implication (from loyal customers)—

risk reduction regarding future cash flows.

Although there is substantial empirical support for many of

the aforementioned effects, the most fundamental finding has to

do with repeat business. There is a large literature on customer

lifetime value (CLV), or customer equity, whereby the eco-

nomic value of repeat business is determined by the discounted

net present value of future cash flows from current customers.

Consistent with the proposition that customer satisfaction has

a positive impact on stock price, research has shown that an

increase in CLV can lead to an increase in stock price (Kumar

and Shah 2009, 2011) and to higher future profits (Venkatesan

and Kumar 2004). Although there are several ways to measure

CLV (Holm, Kumar, and Rohde 2012; Kumar and George

2007), for our purposes and without loss of generalization,

assuming that profit margins are constant, the time period is

infinite, and the customer retention rate does not vary over time,

we can theoretically express customer equity value as follows:

CEV = m

r

1 + i - r

,(1)

where CEV = customer equity value, m = the profit margin

multiple, r = the proportion of retained customers, and i = the

discount rate. By way of example, consider a company in which

75% of customers return as future buyers and the discount rate

is 5%. Solving Equation 1 gives a margin multiple of 2.5. If

customer satisfaction increased and led to a growth in the

proportion of retained customers by, say, 5 percentage points

(r = .8), the corresponding margin multiple would be 3.2—a

growth in equity value of 28%. Note that a fairly small increase

in retention (5 percentage points) leads to a much larger growth

in the value of customer equity (28%). The effect obviously

becomes more pronounced at higher levels of r, but even at

moderate levels, it is quite substantial and of relevance to

investors. Because customer satisfaction is a major contributor

to buyer retention, it follows that it too may affect stock price.

Practically, it may be useful to illustrate a few short examples

of relationships between customer satisfaction and share price

before turning to formal analysis. Consider four firms—Apple,

Netflix, Costco, and Home Depot—over an identical ten-year

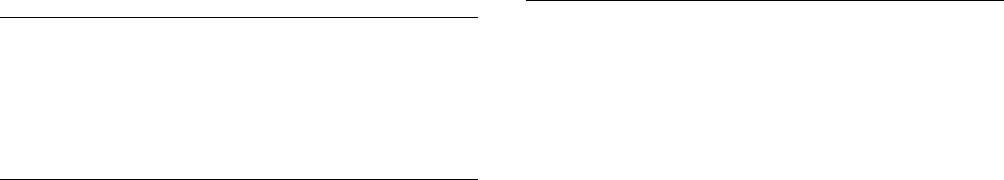

time period. In Figure 1, Panels A–D, we depict the relationship

between ACSI and stock price for these companies.

The most dramatic relationship is the one for Apple. As its

customer satisfaction increased from a middle-of-the pack com-

pany to best in class, Apple’s stock price soared (Figure 1, Panel

A). Netflix depicts a reversal of fortunes in both ACSI and stock

price (Panel B). In contrast to Apple, Netflix already had a

very high level of customer satisfaction when the ACSI began

tracking it. As its ACSI score continued upward, its stock price

did too. However, Netflix frustrated customers by increasing its

prices by 30%–50% in 2011. Both its ACSI and stock price

plummeted. Costco illustrates yet another type of relationship

(Panel C). Here, it is change in the ACSI that is most relevant.

Even though Costco customer satisfaction is high, it is not as

high as that for many other companies. Finally, Home Depot

shows what can happen to a company that starts out with a

reasonable level of customer satisfaction, drops back signifi-

cantly (to a low ACSI score of 66), and later not only recovers

but also achieves a higher ACSI score than it had before the

slump (Panel D). As customer satisfaction deteriorates, Home

Depot’s stock price falls. When customer satisfaction increases

sharply later on, so does the firm’s stock price. These com-

panies illustrate how ACSI and stock price move together in

different ways: from good to superb (Apple); from superb to

weak (Netflix); from good to better (Costco); and from good, to

bad, to better (Home Depot). Although these are just examples

of individual companies, they do show a strong relationship

between customer satisfaction and stock price. Next, we ex-

amine the extent to which these examples can be generalized

in a portfolio of companies, selected on the basis of ACSI data.

Data

Customer Satisfaction Data

The customer satisfaction data used in this study come from

the ACSI, which provides annual customer satisfaction scores

from a latent variable structural equation model estimated from

survey data on customer satisfaction for approximately 300 of

the largest companies, across 45 distinct industries, in the U.S.

consumer market (e.g., Fornell et al. 2006).

2

Data are collected

on a quarterly basis for different industries, with approximately

2

Customer satisfaction is measured for the largest companies in

each industry. Within each industry, those with the largest U.S.

market shares are covered. The sample of measured ACSI com-

panies includes mostly larger consumer goods firms. Although this

means that the ACSI is not perfectly representative of the broader

universe of publicly traded companies, it is in keeping with the prior

literature investigating the impact of satisfaction (and other intan-

gibles) on market performance (Edmans 2011).

94 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

25% of the total annual probability sample of about 70,000

households interviewed each quarter, resulting in annual satis-

faction scores for each company.

3

Although the ACSI is obvi-

ously skewed toward consumer markets, it seems to represent the

overall stock market quite well.

4

Audited Returns and Back-Tested Returns

The other major data source is audited stock portfolio returns

obtained from the same stock fund exami ned in Fornell et al.

(2006). Previous research has not detected an announcement

effect regarding ACSI news releases and press coverage

(Fornell et al. 2006; Raithel et al. 2011; Srinivasan and Hanssens

2009) or has found only a limited effect (Ittner, Larcker, and

Taylor 2009). Accordingly, the trading is based on both levels

and changes in a company’s customer satisfaction score. Stocks

are purchased both before and after the ACSI release date, with

a blackout period of 48 hours surrounding the announcement.

5

In general, access to audited returns data, which is what

this study relies on for its major analysis, is advantageous be-

cause data snooping bias is eliminated (Black 1993; Lo and

MacKinlay 1990; Merton 1987). Data snooping refers to the

reuse of data for model testing. For example, trying out various

rules for stock portfolio construction in a back-testing scenario

is almost always subject to data snooping bias—leading to

stock-picking rules based on sample uniqueness but without

predictive superio rity. There is substantial e vidence that

FIGURE 1

Examples of the ACSI–Stock Price Relationship

A: Apple B: Netflix

spApple ACSI Apple tock rice

Year

$0

$100

$200

$300

$400

$500

$600

65

70

75

80

85

90

Stock Price

ACSI

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Netflix ACSI Netflix stock price

Year

$0

$40

$80

$120

$160

$200

65

70

75

80

85

90

Stock Price

ACSI

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

Home Depot ACSI Home Depot stock price

Year

$0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

60

64

68

72

76

80

Stock Price

ACSI

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Costco ACSI Costco stock price

Year

$0

$20

$40

$60

$80

$100

$120

72

74

76

78

80

82

84

Stock Price

ACSI

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

C: Costco D: Home Depot

3

The ACSI database contains approximately 3,200 firm-year

observations over a 20-year period, with an average customer sat-

isfaction sco re of 76.44 and an average annual standard deviation

of 2.43.

4

For the time period 1997–2003, Fornell et al. (2006) examined

the top 20% ACSI firms and found that they outperformed the Dow

Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) by 21%–40%, but that the bottom

80% ACSI firms had a return virtually identical to the DJIA (20.4%

and 21%, respectively). For this study, the correlation between the

returns of the ACSI universe and the S&P 500 (for the time period

2000–2014) was .88. The reason for the high correspondence between

the ACSI universe returns and S&P returns is probably that consumer

spending is such a large proportion of the gross domestic product and

that many firms covered by ACSI compete in both consumer and

nonconsumer markets.

5

The blackout period is not imposed by regulation, but it is used

to remove any reasonable risk of trading on announcements. Even

though most prior research has not detected a significant

announcement effect, its existence cannot be completely ruled out,

especially as the returns on customer satisfaction become more

widely known. For example, a recent study by Ivanov, Joseph, and

Wintoki (2013) finds that stock trading volume is 2.8% higher on

average during a ten-day period around the ACSI announcements

and that there is a market reaction to these announcements over six

trading days.

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 95

data-driven discovery leads to seriously distorted findings and

that it is endemic in the literature (White 2000). The lack of

credibility is so serious that the SEC prohibits the use of back-

tested results in presentations of stock funds to investors. In

academia, however, back testing is common, presumably

because real returns data are difficult to obtain. The advantage

of back-tested results is that the portfolio construction rules can

be made explicit, but that is of limited value if the process of

how these rules were established is not disclosed. If the rules

were established through trial and error, the predictive powers

of back-tested results are greatly curtailed.

However, even though actual returns are generally pref-

erable, they are not without limitations. They can almost never

be perfectly replicated because, in practice, stock trading rules

are almost never truly formulaic. Most professional inves-

tors require different risk exposure, stop-loss criteria, portfolio

diversification , leverage, and so on. Yet perfect nume rical

replication is not required for generalization or for theory

testing—verification and general principles are. Only audited

returns can provide true numerical verification.

The general trading principle can be succinctly stated as

follows: go long in firms with strong customer satisfaction

(i.e., high and rising levels of ACSI scores relative to other

firms in the same industry), and short in firms with weak

customer satisfaction (i.e., low and declining ACSI scores

relative to other firms in the same industry). This principle

may be operationalized in slightly different ways; the issue is

the extent to which different studies using the same theo-

retical principle, with diff erent operationalizations, arrive at

similar results. Among the studies that h ave examined the

customer satisfaction–stock return relationship, most have ob-

tained similar numer ical results. Indeed, all previous studies

that have analyzed stock returns of firms with strong customer

satisfaction (high levels and positive changes) have reported

numerically large abnormal returns. When the regression esti-

mates, which typically reflect monthly returns in these studies,

are expressed as annual returns, it is evident that the abnormal

returns are very large.

For example, Jacobson and Mizik (2 009a) report risk-

adjusted monthly abnormal returns of .007. Had they expressed

these returns in annual terms, it would have been obvious that a

monthly above-market return of .007 is very high, equaling a

market outperformance of 8.4% per year over ten years, even

after adjustments for additional risk factors—better than almost

any mutual fund over the same time period. Aksoy et al. (2008)

report abnormal annual returns of 10.6% over a different (but

somewhat overlapping) ten-year period. As we show herein,

these estimates are similar to our findings over a time period

50% lon ger. W e retur n to other st udies s ubsequen tly an d

discuss circumstances under which some of them reached

conclusions different to ours, but for now it is important to point

out that even though our main study does not include formulaic

trading rules, it does not follow that the general principle behind

the portfolio construction is insufficient for verification or that

the results cannot be approximated in a meaningfu l way.

In our case, then, we expect that the general principle of

going long in firms with strong customer satisfaction and

short in firms with weak customer satisfaction would lead

to similar returns even though operationalizations of the

principle may differ. We test this prediction by using data

from an additional market and country and, in so doing,

mitigate the strengths and weaknesses of real data versus

back-tested data. In this case, we back test a paper portfolio

based on customer satisfaction data in the United Kingdom

and compare its returns with the Financial Times Stock Ex-

change (FTSE) 100 index. Notwithstanding the limitations

of back test ing, it serves as a complement to the actual and

audited returns data in the U.S. study. By combining actual

and back-tested returns, the weakness in one approach is

compensated by the stre ngth of the other, and vice versa. The

estimated annual abnormal return (12%) in the U.K. study is

fairly similar to what we and others find in the United States

(8.4%–10.8%). The difference is most likely due to the fact

that there are more variables available for adjusting the

returns for risk in the United States and that the U.K. returns

do not take dividends into account. If dividends had been

included, the returns would have been reduced by approx-

imately 2%, bringing the U.K. returns in line with the U.S.

results.

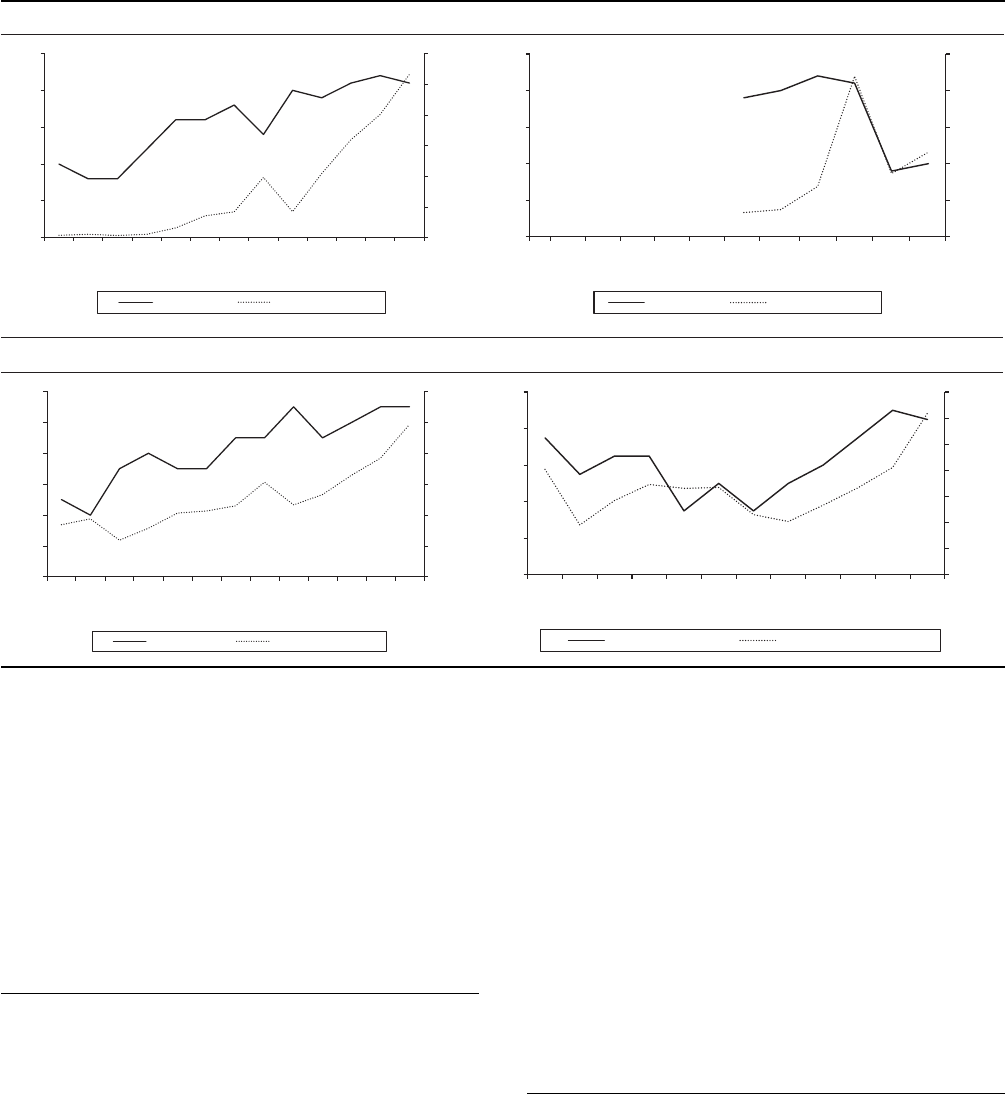

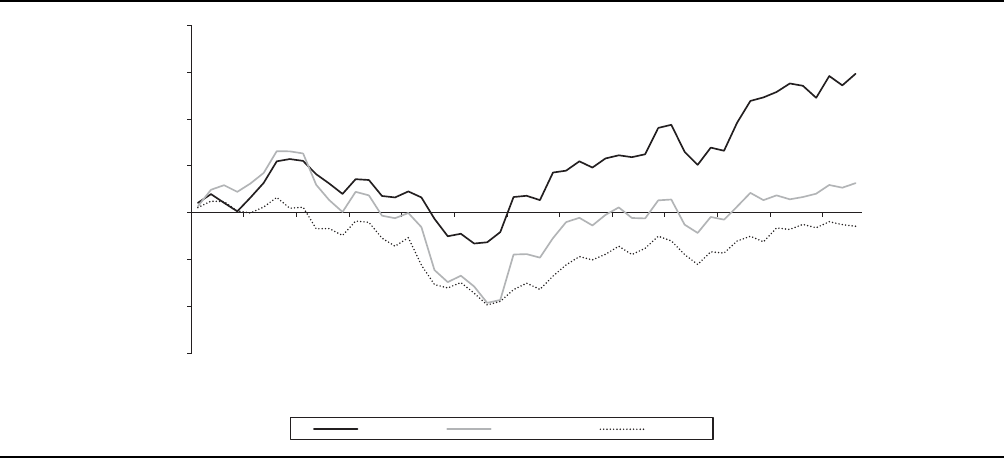

Portfolio Returns

Let us begin with the returns on the U.S. customer satisfaction

portfolio described previously. Figure 2 shows the cumulative,

model-free returns, expressed as the value of $100 invested

from April 2000 through June 2014. The investment grew to

$618 (+518%). Although it might appear that the 2009 re-

cession dip in the portfolio returns in Figure 2 was larger than

market, the opposite is actually the case in terms of percent-

age changes. This finding is consistent with Merrin, Hoffman,

and Pennings (2013), in that customer satisfaction is found to

act as a buffer after the bursting of price bubbles. It is also

evident that the returns are not due to spectacular performance

in a few years and underperformance in others, as is often the

case with mutual funds. As Figure 2 illustrates, the customer

satisfaction returns were higher than the returns for the S&P

500 in 14 of the 15 years, with 2013 as the sole outlier. In view

of the large difference between the S&P 500 and the customer

satisfaction portfolio performance over a long period of time, it

is very unlikely that the result can be explained by known (risk)

factors or sector bias (whether retail, technology, or otherwise).

With a short time period, the impact of such factors could be

substantial, but this is not true in the long run. This is because

investors would have had sufficient time to react, and the

abnormal returns would have been eliminated. In the absence

of these factors, it would seem reasonable to conclude that the

results were essentially driven by customer satisfaction and

that investors in the main were unaware of its effect or its

manifestation. It may be possible, however, that known fac-

tors, to a limited extent, mitigate customer satisfaction returns.

This is what we examine next.

Let us begin the analysis of risk-adjusted returns by using

the standard Sharpe–Lintner CAPM (Lintner 1965a, b; Sharpe

1965):

SAT

it

=a

it

+ b

1

MKT

t

+e

it

,(2)

where SAT

it

= the portfolio return minus the risk-free rate at

time t (month), a

it

= the estimate of risk-adjusted above-market

96 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

returns at time t, MKT

t

(market risk premium) = the market

returns in excess of the risk-free rate at time t, and e=the error

term. We obtained the risk data for this and subsequent equa-

tions from Kenneth French’s website and data library (http://mba.

tuck. dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ken.frenc h/data_library.html).

The results (presented in Table 1) indicate a significant alpha

of .009, equivalent to annualized market risk-adjusted returns of

10.8%, as well as a significant market beta of .692.

Jacobson and Mizik (2009a) claim that that abnormal

returns from satisfaction are limited to the technology sector,

where they found adjusted abnormal annual returns of 32.4%–

38.4% over ten years. No commercially available portfolio of

common stock has ever even been close to outperforming the

market by 32%–38% annually over a period of ten years, so

there is reason to be somewhat skeptical about these num-

bers. This finding also seems inconsistent with other results

reported by Jacobson and Mizik. When technology (and

utilities) is removed from the portfolio, the abnormal returns

are reduced by only 1.0%–3.3% for the full sample (depending

on the model they use), which must be statistically insignificant

if 6.4%–8.4% is insignificantly different from zero (or nearly

so for the latter alpha), as they report in their study.

Even though we could not find any theoretical or empirical

justification for treating technology differently, we did check

to determine whether the results changed under narrower mar-

ket indices, such as NASDAQ and the Dow Jones Industrial

Average (DJIA). The estimated annual alpha (adjusting for

dividends as an average of 2%) relative to NASDAQ is 11.2%,

slightly higher than the Fama–French benchmark (MKT) at

10.8%, and the alpha with the DJIA is 10.0%, slightly lower.

If technology stocks were much more sensitive to customer

satisfaction, an even larger alpha would be expected.

FIGURE 2

Cumulative Returns on $100 Invested in Customer Satisfaction: Port folio Versus the S&P 500 (April 2000

Through June 2014)

$617.59

$130.81

Mar 2000

Nov 2000

Jul 2001

Mar 2002

Nov 2002

Jul 2003

Mar 2004

Nov 2004

Jul 2005

Mar 2006

Nov 2006

Jul 2007

Mar 2008

Nov 2008

Jul 2009

Mar 2010

Nov 2010

Jul 2011

Mar 2012

Nov 2012

Jul 2013

Mar 2014

$0

$100

$200

$300

$400

$500

$600

$700

Portfolio S&P 500

TABLE 1

Risk-Factor Model Results

Sharpe–Lintner

CAPM

Fama–French

Three-Factor CAPM

Carhart Four-Factor

CAPM

Winsorized (95%) Carhart

Four-Factor CAPM

a .009*** .009*** .009*** .009***

a (%) 10.8% 10.8% 10.8% 10.8%

MKT .692*** .654*** .622*** .608***

SMB — .171* .183** .072

HML — .005 -.003 .028

MOM ——-.062* .050

*p < .05 (one-tailed).

**p < .01 (one-tailed).

***p < .001 (one-tailed).

Notes: MKT = monthly market returns excess of the risk-free rate; SMB = size risk-factor returns; HML = value risk-factor returns; MOM = momentum

risk-factor returns.

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 97

Other known factors cannot be expected to do much

better, but we examine the extent to which they mitigate the

returns. Adding risk factors proposed by Fama and MacBeth

(1973) and Fama and French (1993, 2004), we specify a three-

factor model:

SAT

it

=a

it

+ b

1

MKT

t

+ b

2

SMB

t

+ b

3

HML

t

+e

it

,(3)

where the additional factors are SMB

t

(stock size risk

premium) = the size risk-factor returns at time t and HML

t

(stock growth risk premium) = the value risk-factor returns

at time t.

With respect to alpha, the result is identical to the original

CAPM (an alpha of .009, or 10.8% annual return). The mar-

ket beta is somewhat smaller at .654, as some of the effect is

picked up by the small stock risk factor (.171). The effect of

the growth risk premium is not significant. We are not aware

of any theoretical basis for interpreting the size risk-factor

returns effect, even though it is statistically significant at .05.

The ACSI is, by design, dominated by large cap stocks. The

returns of small stocks minus big stocks do covary with the

customer satisfaction returns (of large stocks), but that asso-

ciation is most likely a spurious one.

Finally, we add another risk factor, suggested by Carhart

(1997)—MOM

t

(stock momentum risk premium) = the mo-

mentum risk-factor returns at time t—but this factor is not

significant and the results do not change.

SAT

it

=a

it

+ b

1

MKT

t

+ b

2

SMB

t

+ b

3

HML

t

+ b

4

MOM

t

+e

it

:(4)

To summarize, the results show an annual four-factor alpha of

10.8% over a 15-year period from a stock fund long in strong

customer satisfaction stocks and short in weak customer

satisfaction stocks. The results are unchanged even when

more risk factors are added to the model, but the results are at

odds with the conclusions, though not necessarily with the

numerical results of Jacobson and Mizik (2009a), Bell,

Ledoit, and Wolf (2014), and Ittner, Larcker, and Taylor

(2009). There are several reasons for this discrepancy beyond

the longer time period we used.

First, consider Ittner, Larcker, and Taylor (2009),

who report that customer satisfaction has incremental

informational value beyond financial information but find

no abnormal returns or evidence of mispricing. However,

levels of customer satisfactionaredisregardedintheir

portfolio construction; only changes are deemed relevant.

The assumption is that customer satisfaction levels are

already impou nded in stock prices—consistent with the

efficient market hypothesis of zero alpha. As ide fr om

ignoring information implied by CLV (Equation 1),

which posits that (high) levels are critical because of

their exponential impact on value, there is the logic al

challenge of assuming that levels of customer satisfaction

are already reflected in share prices when that very

assumption (market efficiency) is being tested. High serial

correlation notwithstanding, the importance of levels (in

combination with changes) is that firms with high levels of

customer satisfaction (and thus, retention) create much greater

customer equity value than firms with low levels of customer

satisfaction, even if the latter firms also have increasing

satisfaction.

Two other studies (Bell, Ledoit, and Wolf 2014; Jacobson

and Mizik 2009a) obtain large positive alphas but likewise

conclude that these abnormal returns cannot be distinguished

from chance. Jacobson and Mizik (2009a) also apply a con-

ditional model with time-varying parameters and find an

alpha of zero.

6

However, such a result would require the

correlation between alpha and beta to be “enormous” (to cite

Lewellen and Nagel 2006). We find that correlation to be no

greater than .36, but that may not matter because time has

passed and the prediction of zero alpha is now testable and

shown to be inaccurate.

The Earnings Effect

Systematic underpricing of customer satisfaction could be due

to multiple factors, but recent research has suggested earnings

surprises as a major factor (Ngobo, Casta, and Ramond 2012;

O’Sullivan and McCallig 2009). That is, investors do not re-

act to information about customer satisfaction per se either be-

cause they are no t aware of it or because they place little trust

in it until it is substantiated by financials. Inst ead, they react to

earnings surprises, which, in turn, may have been caused by

strengthening or weakening customer satisfaction. Thus, we

examine the impact of customer satisfaction on both earnings

and earnings surprises.

Over time, the portfolio has held substantially more longs

than shorts (920 vs. 88). In Table 2, the first two mean scores

reflect average earnings surprises for the long (3.3 cents per

share) and short (.9 cents per share) books, respectively. The

long positions had positive quarterly earnings surprises 60%

of the time. That may not, in itself, suggest anything out of the

ordinary, because most S&P stocks tend to beat earnings

estimates (Jakab 2012). However, only 37% of the longs had

negative earnings surprises. The short positions had negative

6

Unlike the unconditional (or static) CAPM, the conditional

CAPM suggests that beta (or exposure to market risk) varies over

time, as rational investors anticipate future investment conditions

that could change adversely and thus alter their investment strategies

intertemporally. According to the logic of the conditional CAPM,

investor expectations lead to a correlation between beta and market

risk premium that also varies over time, and that can help better

explain contemporaneous market risk premium (or alpha). Either

short-window regressions testing for the existence of intertemporal

variation in beta (Adrian and Franzoni 2009; Lewellen and Nagel

2006) or a version of the CAPM that integrates lagged terms for

market risk premium and beta (alpha

t-1

· beta

t-1

) (Jagannathan and

Wang 1996) are used to test the conditional CAPM. Although results

from these studies also vary, and although a debate in the finance

literature over the usefulness of the conditional CAPM in better

explaining asset pricing anomalies remains active, most research has

found only a marginally better explanation of risk premiums through

the conditional CAPM. Some studies have found that the conditional

CAPM decreases the size of the market risk premium moderately or

slightly but without alpha falling to zero or becoming statistically

insignificant (Adrian and Franzoni 2009; Jagannathan and Wang

1996). Other studies have found virtually no impact of the condi-

tional CAPM, suggesting that the correlation between alpha and beta

over time would need to be “enormous” to explain away asset

pricing anomalies (Lewellen and Nagel 2006). Yet all agree that the

intertemporal covariance between beta and alpha needs to be very

large for the conditional CAPM to improve explanation of market

risk premiums from the CAPM.

98 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

quarterly earnings surpr ises 49% of the time, much more

frequently than S&P 500 firms; they also had 49% positive

earnings surprises, less common than S&P 500 firms. At first

glance, these findings would seem to suggest that strong

customer satisfaction is more closely associated with posi-

tive earnings surprises than weak customer satisfaction with

negative earnings surprises. Yet looking at quarterly earnings

surprises in dollar terms (the second set of mean scores in

Table 2, with mean earnings per share [EPS] multiplied by

common shares outstanding), negative earnings surprises are

larger: approximately –$62.4 million on average for the shorts

versus +$26.1 million for the longs.

Accordingly, firms with strong (weak) customer sat-

isfaction are more likely to have positive (negative) earnings

surprises, suggesting that investors react to tangible con-

sequences of customer satisfacti on and not necessarily to

information about customer satisfaction itself. This effect

seems to overwhelm the potentially countervailing impact

from the accounting practice of exp ensing, rather than

capitalizing, investments in customer service improve-

ments. Unless the increased service improvement is due to

technology investment or some other capital expenditure,

expensing can lead firms with strong short-term earnings

growth and weak customer satisfaction to be overvalued by

the market, whereas firms with weak short-term earnings

growth but strong customer satisfaction would be under-

valued. It is easy to find conditions under which this can

happen.

For example, on the one hand, employee turnover or cost

cutting in customer service may have a positive effect on

short-term earnings but a detrimental impact on customer

satisfaction, thus eroding future earnings power. On the other

hand, a firm’ s investment in better customer service may

have a positive effect on customer satisfaction and lead to

greater future earnings potential, but—if the investment is

expensed instead of capitalized over time—short-term earn-

ings would be negatively affected. If, under these circum-

stances, investors pay attention to accounting information but

not to prior and subsequent customer satisfaction, the resulting

valuation bias might be considerable. Even if 37% of the

companies with strong customer satisfaction did indeed have

negative earnings surprises, that is not enough to offset the

cumulative positive earnings surprises for companies with

strong customer satisfaction.

In light of these results, it seem s that there is a relationship

between customer satisfaction and earnings surprises, which

we confirm by combining long and short positions and esti-

mating the following regression:

SUR

it…t+3

= b

0

+ b

1

CS

it

+ b

2

DCS

it

+ b

3

ðCS

it

·DCS

it

Þ +e

it

,(5)

where SUR is earnings surprise for company i at time t, mea-

sured each quarter following the inclusion of the stock in

either the long or the short book as quarterly EPS minus the

Institutional Brokers Estimate System quarterly median

analyst forecast; CS is the annual ACSI customer satisfac-

tion score; DCS is changes from the prior year in the annual

ACSI customer satisfaction score; and CS ·DCS is the

interaction effect between the two.

7

Table 3 presents the

results. The effect of ACSI and the interaction between ACSI

changes and levels are significant. The ACSI changes alone

are not significant. This result u nderscores the importance of

the standard customer value equation (Equation 1) in that

changes are conditional on high values to have an effect.

Unless there is a change from a level that is already high, there

is no effect on earnings surprises from a change in customer

satisfaction.

If customer satisfaction leads to earnings surprises in

the manner suggested by the estimates in Equation 5 and in

TABLE 2

Customer Satisfaction Portfolio Earnings Surprises

N M Min Max SD

Long Positions

EPS - median EPS forecast 920 .0330 -6.3867 3.9900 .5999

EPS - median EPS forecast ($ millions) 920 26.1132 -6,663.75 2,477.3910 432.8846

Short Positions

EPS - median EPS forecast 88 .0086 -2.1033 3.7200 .6029

EPS - median EPS forecast ($ millions) 88 -62.3988 -3,497.84 697.6367 447.2678

Notes: Earnings surprise = quarterly earnings per share - median earnings per share forecast (source: Bloomberg L.P.). A t-test of the difference

between long and the short positions shows that the long positions had significantly more positive earnings surprises than the short positions

(p < .05, one-tailed).

TABLE 3

The Effect of Customer Satisfaction on

Earnings Surprises

Coefficient SE

a .030 .019

CS .006* .003

DCS -.795 .582

CS ·DCS .120* .062

*p < .05 (two-tailed).

Notes: CS = annual ACSI customer satisfaction score; DCS = changes

in the annual ACSI customer satisfaction score; CS x DCS = the

interaction effect between CS and DCS.

7

Because ACSI scores are constant from the quarter they are

released until new results come out 12 months later, and because

earnings surprises are quarterly, the same independent variable is

applied to four different dependent variables further and further into

the future (current quarter, next quarter, two quarters ahead, etc.).

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 99

Tables 2 and 3, it might also have an impact on earnings

themselves, as we po stulate in Equation 6:

EPS

it…t+3

= b

0

+ b

1

CS

it

+ b

2

DCS

it

+ b

3

ðCS

it

·DCS

it

Þ +e

it

,(6)

where EPS is earnings for company i at time t, measured each

quarter following the inclusion of the stock in either the long or

the short book as quarterly earnings per share; CS is the annual

ACSI customer satisfaction score; DCS is changes in the annual

ACSI score; and CS ·DCS is the interaction effect between the

two. Table 4 provides the results, which are consistent with the

effect on earnings surprises. The level of customer satisfaction

is significant, as is the interaction between levels and changes.

Changes by themselves are not significant. Unless changes are

accompanied with high levels of customer satisfaction, they do

not seem to have an impact on earnings.

We have examined earnings, earnings surprises, and how

they are affected by customer satisfaction. Next, we investi-

gate whether stock returns on earnings explain the effect of

customer satisfaction returns. If they do, the substantial alphas

shown previously might be reduced. A new five-factor model

proposed by Fama and French (2015) enables us to estimate

the effect of earnings returns on customer satisfaction returns.

In the new model, earnings are defined as annual revenues

minus cost of goods sold; interest expense; and selling,

general, and administrative expenses at time t - 1. The factor,

termed RMW by Fama and French, is the difference in

returns between diversified portfolios with robust versus

weak profitability. In that sense, it is similar to the customer

satisfaction portfolio, which, by going long and short, respec-

tively, also becomes the difference in returns between robust

and weak custom er satis fa cti on. The Fam a–French model

also includes an investment factor (CMA); however, we do

not discuss it further because it turns out to be irrelevant in

this circumstance. Accordingly, we specify the five-factor

model as follows:

SAT

it

=a

it

+ b

1

MKT

t

+ b

2

SMB

t

+ b

3

HML

t

+ b

4

RMW

t

+ b

5

CMA

t

+e

it

:

(7)

An important finding is that earnings mitigate the effect of

customer satisfaction on stock returns. The estimate of abnormal

returns is reduced from .009 to .007, or from an annualized

return of 10.8%–8.4%. However, it is not surprising that cus-

tomer satisfaction and profitability are related. The literature

supports such a finding (Morgan and Rego 2006), though it is

not always the case that high customer satisfaction has a positive

impact on profitability. Yet when buyers have choice and are

reasonably well informed, it is usually the case.

The Winsorized estimates in Table 5 are consistent with

the full sample results, but the effect of earnings is smaller

and the abnormal returns larger. This means that the outliers

are more strongly correlated to earnings returns (as mea-

sured by RMW). Again, this follow s from the exponential

effects encapsulated in Equation 1: stocks with the highest

(lowest) return had the highest (lowest) correlation to earn-

ings returns.

In addition to the models common in the academic fi-

nancial literature, there are also commercially available mul-

tifactor models. As we have seen, when controlling for risk

factors such as market, size, value, profitability, momentum,

and so forth, the customer satisfaction alpha survives. Does it

also survive when using an expanded multifactor model? The

most well-known of these types of models is the model

introduced by Rosenberg and McKibben (1973) and made

available by Barra Inc., until the firm was acquired by MSCI in

2004. Table 6 presents the results from applying the most

current commercially available Barra USE4 comprehensive

trading model, using customer satisfaction returns from July

2006 to November 2013. This analysis was performed by

Morgan Stanley.

Of these factors, the estimated factor loading betas for

technology and retail are significant at the .05 level. This is not

surprising, because technology stocks in general did well during

this time period and because the ACSI tracks both consumer

technology and many retail firms. No other factors were sig-

nificant. Approximately 80% of the variance was unaccounted

for, taking all factors into account. Accordingly, there seems to

be no known factor that can explain the market outperformance;

it is due to either customer satisfaction or some yet unknown

factor that is correlated with customer satisfaction.

Generalizability

We are not aware of previous research reporting higher risk-

adjusted returns for an intangible asset other than those found

TABLE 4

The Effect of Customer Satisfaction on EPS

Coefficient SE

a .630*** .028

CS .032*** .005

DCS -.673 .882

CS ·DCS .249** .094

**p < .01 (two-tailed).

***p < .001 (two-tailed).

Notes: CS = annual ACSI customer satisfaction score; DCS = changes

in the annual ACSI customer satisfaction score; CS x DCS = the

interaction effect between CS and DCS.

TABLE 5

Five-Factor Model Results

Fama–French

Five-Factor CAPM

Winsorized (95%)

Fama–French

Five-Factor CAPM

a .007*** .008***

a (%) 8.4% 9.6%

MKT .718*** .626***

SMB .213** .124*

HML -.142 -.059

RMW .392** .234*

CMA .117 .059

*p < .05 (one-tailed).

**p < .01 (one-tailed).

***p < .001 (one-tailed).

Notes: MKT = monthly market returns excess of the risk-free rate;

SMB = size risk-factor returns; HML = value risk-factor returns;

RMW = profitability risk-factor returns; CMA = investment risk-

factor returns.

100 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

in this study. For example, annual abnormal returns from

research and development have been estimated at 4.6% (Lev

and Sougiannis 1996) and 3.5% (Edmans 2011) from employee

satisfaction. Bec ause the customer satisfaction returns are so

different than the returns on other intangibles, they call for extra

efforts in validation. We are fortunate in the sense that we have

access to comparable data in which both settings and time

periods are different and in which we can use trading rules based

on the same principle but with a different operationalization.

Ultimately, observed empirical regularities need not only to be

confirmed in time and space but also to be understood in terms

of theory such that the conditions under which they occur can

be specified (competitive consumer markets, repeat purchases,

market failure, etc.) and under which they do not. Next, we

discuss the former condition.

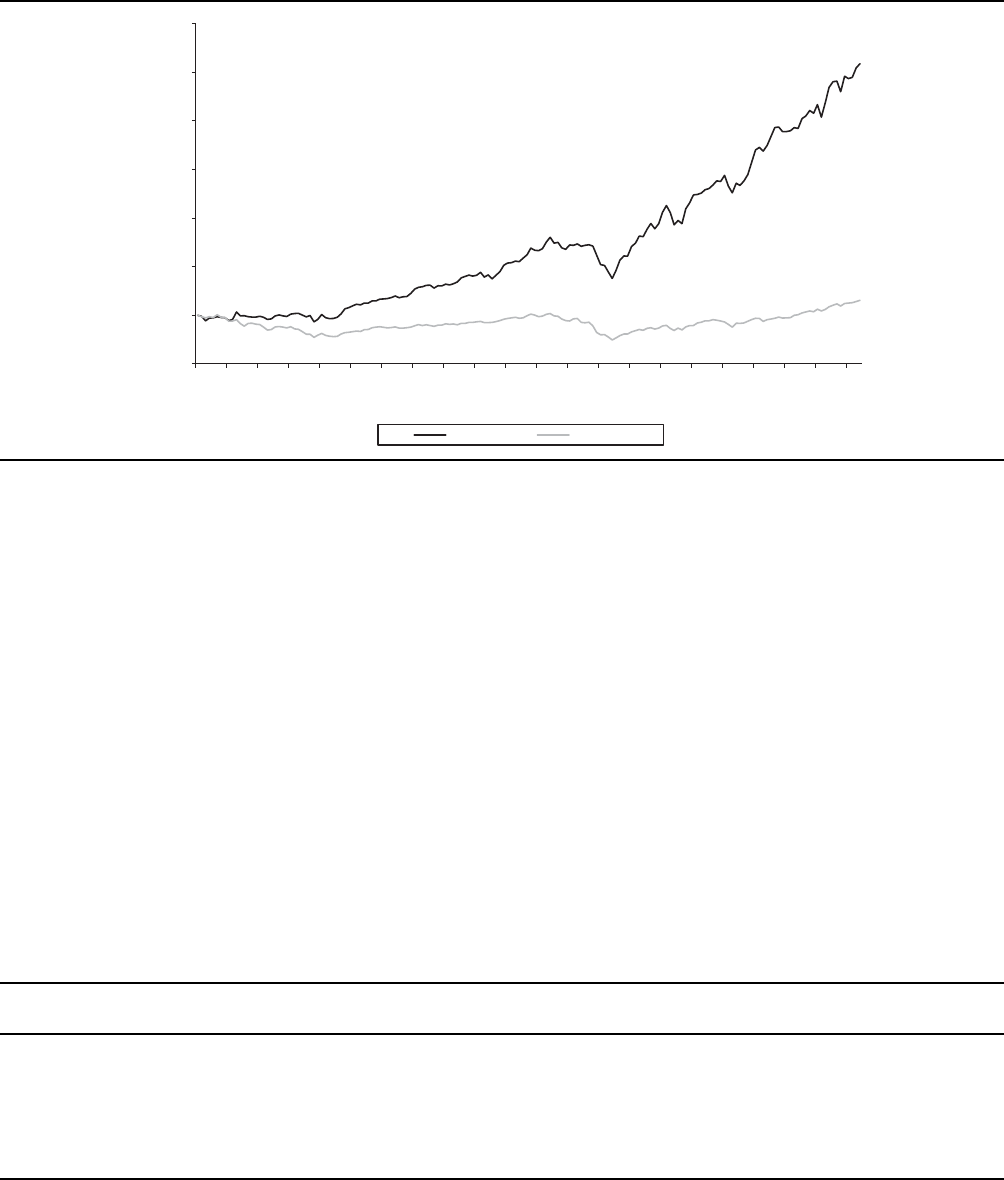

Confirmatory Evidence

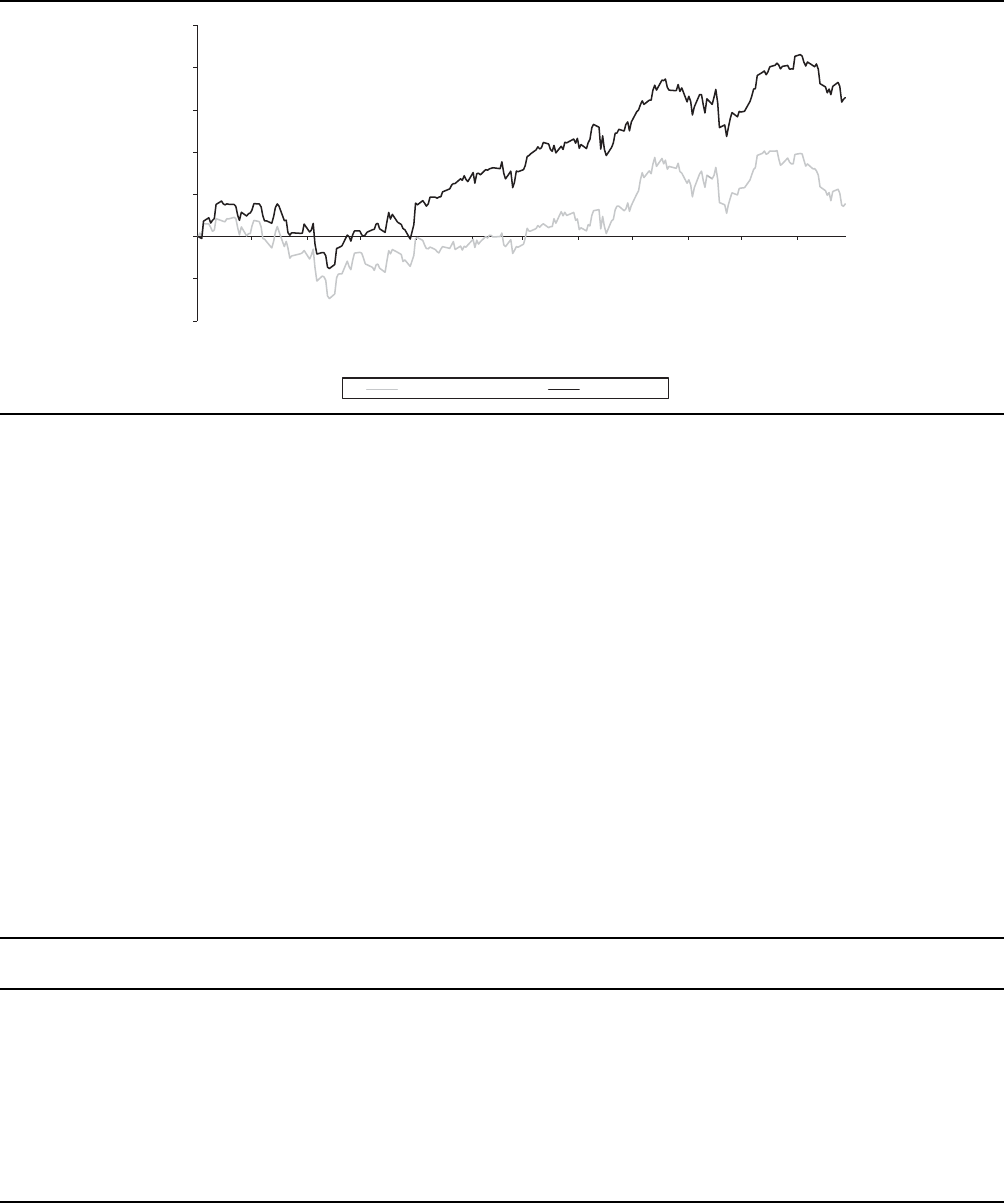

Do these results generalize across time and space? As to the

question of whether the results hold in a different stock

market and are robust with respect to simpler but perfectly

replicable trading rules, the analysis is extended to the United

Kingdom, where the returns are not obtained from audited

profits, but from back testing. Although customer satisfaction

data comparable to the United States do not exist for many

countries, there is a similar customer satisfaction index in the

United Kingdom: the National Customer Satisfaction Index

(NCSI-UK, www.ncsiuk.com). It uses the same latent struc-

tural equation model as the ACSI and it is also updated

quarterly. The U.K. data were available from 2007 to 2011

from the customer satisfaction universe of publicly traded

firms (74 companies). We obtained the returns with simple

trading rules that generated two portfolios: the first portfolio

comprised the top 50% of companies in customer satisfac-

tion, and the second contained the bottom 50%, all equally

weighted.

8

We purchased stocks at the end-of-month closing

price for the quarter in which NCSI-UK results were announced

and held all stocks for one calendar year. Each quarter, we

examined the stocks with new customer satisfaction infor-

mation and adjusted the portfolios accordingly. If a stock was

no longer in the top 50%, we moved it from the first portfolio

to the second portfolio, and vice versa. Figure 3 provides

the model-free returns (trading costs excluded) on the two

portfolios compared with returns on the FTSE 100.

Except for a short period following inception, the top

50% customer satisfaction portfolio outperformed both the

FTSE and the bottom 50% portfolio. From August 2007 to

April 2011, the top 50% portfolio earned a (model-free)

return of 59%. The bottom 50% portfolio returned 13%,

and the FTSE had a return of –6%, all model free. The

estimated CAPM alpha was .010 (12% annualized) for the top

50% portfolio, compared with .005 (6% annualized) for the

bottom 50% portfolio. The former was significant at the .01

level; the latter was insignificant. The market beta coefficient

was significant at the .001 level for both portfolios; it was very

high for the bottom 50% portfolio at 1.163 and substantially

lower for the top 50% portfolio at .759.

The estimated alpha for the top 50% customer satisfaction

portfolio is large and, at an annualized rate of 12.0%, similar

to the U.S. alpha at 10.8%. The alpha of the bottom 50%

customer satisfaction portfolio is not significant, but it might

still seem odd that stocks of the weakest 50% customer sat-

isfaction companies did better than market. The reason is

probably an effect of beta (i.e., the regression coefficient for

the FTSE 100), as the market moved up sharply after the

2007–2008 recession. As we have mentioned, the beta for

the bottom 50% portfolio was 1.163, compared with .759 for

the top 50% portfolio. In other words, high customer sat-

isfaction reduced market exposure, whereas low customer

satisfaction exacerbated it. Overall, the real audited profitab-

normal returns to customer satisfaction in the United States

correspond well to the back-tested paper profits returns in the

United Kingdom.

TABLE 6

Barra USE4 Model Results

Factor Coefficient

Technology .30*

Retail .24*

Small-large .20

Volatility large cap .12

OTM put .24

EM-dev. .10

Momentum .06

Financials -.13

Japan -.05

Energy -.07

Industrials .11

Health care -.05

Europe .06

Illiquidity .02

Credit .04

Market -.06

*p < .05 (two-tailed).

Notes: Technology = long technology growth stocks; Retail = long con-

sumer, developed market bias; Small-large = long small caps,

short large caps; Volatility large cap = long volume, large cap

exposure; OTM put = long tail protection , downside exposure

management; EM-dev. = emerging markets bias, commodity bias;

Momentum = long momentum stocks, trading style; Financials =

short financials/real estate, long growth/short value; Japan = short

bias Japan, long carry trades; Energy = short global growth, long

transports/developed markets; Industrial s = long cyclicals/long

deep value stocks; Health care = short health care biotech,

short cyclicals; Europe = long bias Europe, long dollar protection;

Illiquidity = long less liquid stocks, long credit; Credit = long credit

sensitive equities; Market = short global equity. The Barra model

results were prepared by Morgan Stanley.

8

We assigned all subsidiaries covered by the NCSI-UK the stock

prices of their parent company and deleted all private or government-

owned compa nies from the dat a set prior to analysis. The U.K. data

include o nly one manufacturing industry (autos), so the concen-

tration bias that would result from taking the top 50% firms in the

ACSI does not exist. Even though data relating to the Fama–French

risk factors a re not readily available in the United Kingdom, there

is no a priori reason to suggest that these factors would be relevant

when they were not significant in the U.S. study (see also Griffin

2002). Accordingly, we analyze t he U.K. data with the s tandard

Sharpe–Lintner CAPM.

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 101

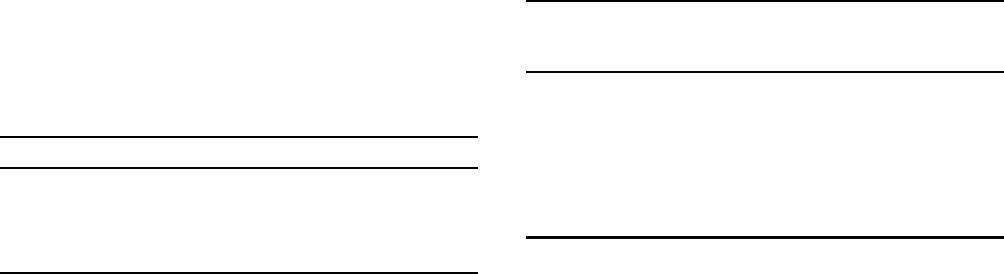

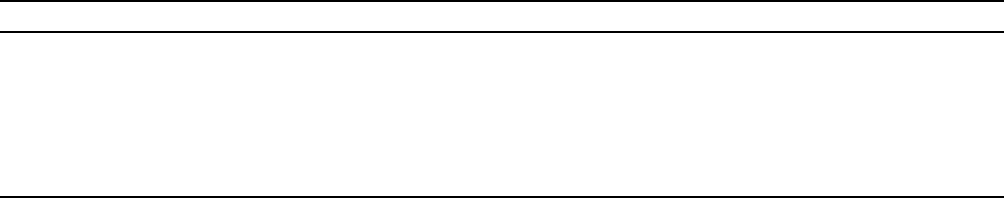

Boundary Conditions

As for boundary conditions and disconfirmatory evidence

relating to our findings, let us examine the periods of time

when the results deviated from the overall time period.

Figure 4 shows that from September 2012 to August 2013,

the stocks of companies with strong customer satisfaction

underperformed the S&P 500. As a result, the satisfaction

portfolio returns for the full year of 2013 were lower than

market. In other words, strong customer satisfaction did not

produce a positive alpha during this period or during 2013.

Because this was the only year of underperformance, it might

be justified to consi der it a chance incident. Nonetheless, the

time period seems long enough to warrant closer examina-

tion, albeit not persistent enough for statistical inference.

In 2013 , the long-s hort customer satisfaction portfolio

returned 21%, its long book was up 25% (both model free), and

the S&P 500 was up 30%. According to Xydias (2013), not only

was the stock market rally one of the broadest in history, but

firms with weak balance sheets outperformed those with strong

balance sheets. There were other idiosyncrasies as well. The

most heavily shorted stocks dramatically outperformed the

market indices. Specifically, the 100 most heavily shorted stocks

in the Russell 3000 index were up 34%, while the index itself

was up 18%. The best performing stocks also had lower cus-

tomer satisfaction than the average stock. The best 25 stock

performers in the ACSI universe had an exceptionally high

average return of 95%, but their average ACSI score was only

75, lower than the average of the longs in the portfolio (82) as

well as the overall ACSI average (77).

With little or no economic justification, there were also

massive reversals in stock returns, from high to low and vice

versa. During the 2011–2012 time period, the top 25 ACSI

universe stock s in terms of returns—with an average return of

95% in 2012–2013—returned only 1.7% on average over the

previous 12 months. The S&P 500 stocks had a similar re-

versal. As Table 7 shows, the top 100 stock performers in the

12-month 2012–2013 period had dramatically greater returns

when compared with the prior 12-month 2011–2012 period

and greatly outperformed the S&P average. Specifically, the

top 100 returned 60% in 2012–2013, but these stocks

returned only 8% in 2011–2012. The corresponding returns

for the remainder of the S&P were 16% and 13%, and for the

total S&P 500, 14% and 24%.

Given that there was a significa nt reversal in stock returns

both for the ACSI universe and for the S&P 500, what do the

data suggest regarding the justification of these reversals on

the basis of revenue and earnings? As Table 7 shows, the top

25 ACSI universe stock performers in 2012–2013 had an

average trailing 12-month revenue growth of 6.7%. This was

lower than the long stocks in the portfolio, which had a

revenue growth of 7.8%, but slightly higher than both the

average ACSI stock (at 5.6%) and the average S&P 500

stock (at 5.7%). Accordingly, the higher share prices could

hardly be justified from revenue growth. Were they driven by

earnings growth? As Table 7 shows, the trailing 12-month

EPS growth for the top 25 ACSI stock performers was 33%

during the underperformance period, compared with 12% for

the ACSI universe, 11% for the long portfolio, 10% for the

average S&P 500 stock, and 17% for the top 100 S&P 500

stock performers in 2012–2013. That is, the top stock

performers did have substantially higher EPS growth.

However, the multiples for the EPS increase on stock price were

FIGURE 3

Cumulative Returns on £100 Invested in Customer Satisfaction: High NCSI-UK Portfolio, Low NCSI-UK

Portfolio, and the FTSE 100

£159.3

£112.7

£94.3

–60%

–40%

–20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

Top 50% Bottom 50% FTSE

Apr 2007

Aug 2007

Dec 2007

Apr 2008

Aug 2008

Dec 2008

Apr 2009

Aug 2009

Dec 2009

Apr 2010

Aug 2010

Dec 2010

Apr 2011

Notes: The high NCSI-UK portfolio consists of the top 50% of measured companies in customer satisfaction; the low NCSI-UK portfolio consists of

the bottom 50% of measured companies in customer satisfaction.

102 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

extraordinarily high. For example, the top 100 S&P 500 stock

performers had EPS growth 63% greater than the average S&P

firm, but a stock return 153% greater. The top 25 ACSI stock

performers had EPS growth 194% greater than the long stocks,

but a stock return 417% greater.

If increasing stock price cannot be justified by revenue

growth but rather is driven by a very large increase in multiples

of EPS growth, did these stock prices rise because they were

“cheap”? Table 8 provides some statistics answering this

question.

The top 25 ACSI stocks in 2012–2013 had an average P/E

ratio of 14.98 in 2011–2012. This compares with a P/E ratio

of 17.64 for the long book and a P/E ratio of 18.24 for the

S&P 500. Thus, if the P/E is interpreted as the relative price

of a stock, then the long stocks were notably more expensive

than the top 25 stock performers. Again, the S&P shows a

similar pattern. The average S&P 500 stock was 28% higher

in P/E ratio than the subsequent top 100 stock performers.

Overall, the evidence suggests that the market exhibited

unusual characteristics during the 2012–2013 time period.

In addition to an unusually broad rally and above-market

performance by stocks with weak balance sheets and by those

most shorted, there was a significant reversal in stock returns

between 2011–2012 and 2012–2013 for both the ACSI

universe and the S&P 500. It is not that the stocks that did

well in 2011–2012 did poorly in 2012–2013, but they did not

do as well as the (previous) underperformers of 2011–2012.

There is no evidence to suggest that the reversal is due to

differences in revenue increases, but some of the reversal

seems to be due to differences in earnings increases. There

were lower P/E ratios for the stocks that gained the most

and evidence that the investors preferred lower-priced stock

even without relating price to earnings. In 2011–2012, the

long-book customer satisfaction portfolio stocks were priced

(P/E) 100% higher than the 2012–2013 top 25 ACSI stock

performers. Even though the underperforming period began

FIGURE 4

Customer Satisfaction Portfolio Versus the S&P 500 (September 2012–August 2013)

3.3%

16.1%

–10%

–5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

Satisfaction portfolio S&P 500

Sep 2012

Oct 2012

Nov 2012

Dec 2012

Jan 2013

Feb 2013

Mar 2013

Apr 2013

May 2013

Jun 2013

Jul 2013

Aug 2013

TABLE 7

Satisfaction Portfolio and S&P 500 Stock Returns, Revenue Growth, and EPS Growth

2011–2012

Avg. Ret. %

2012–2013

Avg. Ret. %

2013 T12M

EPS Growth

2013 T12M

Rev Growth

ACSI

Absolute D

ACSI %

D

ACSI

Mean

ACSI

Median

Satisfaction Long Portfolio

Top 25 in ACSI 1.7% 94.6% 33.2% 6.7% .63 .9% 75.0 77.0

Bottom 111 in ACSI 17.3% 15.3% 7.3% 5.3% .87 1.2% 78.8 80.0

Total ACSI 14.4% 29.9% 12.1% 5.6% .82 1.2% 76.9 79.0

Total satisfaction portfolio 17.0% 18.3% 11.3% 7.8% 2.24 2.9% 81.9 83.0

S&P 500

Top 100 S&P 500 8.4% 60.1% 16.5% 7.8% ————

Bottom 349 S&P 500 15.6% 13.4% 8.3% 5.1% ————

Total S&P 500 14.0% 23.8% 10.1% 5.7% ————

Notes: Avg. Ret. % = average stock return percentage; T12M EPS Growth = trailing 12-month revenue growth; T12M Rev Growth = trailing 12-month

revenue growth. For the satisfaction portfolio, among the 235+ companies measured in ACSI 136 were both publicly traded and had data

available during the entire time period examined, resulting in a comparison between the Top 25 in satisfaction and the Bottom 111 in

satisfaction. For the S&P 500, 449 companies were available during the entire time period examined, resulting in a comparison between the

Top 100 in returns and the Bottom 349.

Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction / 103

in the fourth quarter of 2012, the calendar year returns for

2012 were consistent with prior years, with an above-market

return of 12%.

In summary, the large number of market idiosyncrasies

during the 2012–2013 time period accounts for a large por-

tion of the customer satisfaction underperformance during

this time period. It was an unusual market in many ways:

stocks with weak balance sheets did better than stocks with

strong balance sheets; companies with weak customer sat-

isfaction did better than companies with strong customer

satisfaction; there was a massive reversal in stock price

growth from compa nies that previously had strong growth

to companies that had had weak growth; the most heavily

shorted stocks had much higher return than market; stocks

with low P/E ratios performed bett er than stocks with high

P/E ratios; and stocks with low absolute prices also did bet-

ter. The better-performing stocks did not have superior revenue

growth, but they did show greater percentage earnings growth.

However, they also appear to have been unusually well-rewarded

by investors for those earnings.

Even with the many oddities of the 2012–2013 stock

market, it does suggest that a stock-picking strategy based on a

rather limited universe (firms tracked by the ACSI) is not likely

to outperform the market all the time. Unless there is large

variance in temporal customer satisfaction and, thus, much

turnover in the portfolio, holdings will eventually be domi-

nated by high-priced stocks. The price differential, whether in

absolute price or relative to earnings, may well make lower-

priced stocks appear to be bargains, largely independent of

their fundamentals. At some point, however, fundamentals will

matter again and demand will shift back. It is not clear how

long that usually takes, but in view of the finding that the

portfolio produced higher-than-market returns for 14 years and

less-than-market returns for 12 months, the period is probably

rarely much longer than 1 year.

Discussion

The findings presented in this study suggest that risk-adjusted

stock returns on customer satisfaction are significantly above

market and that these abnormal returns are robust to a variety of

alternative explanations such as size, value, and momentum

risk factors as well as data snooping. Strategically, this places

emphasis on customer satisfaction as an important intangi-

ble marketing asset, also labeled as an operational “customer

mindset” performance variable by Katsikeas et al. (2016).

Importantly, it also highlights marketing’s value to the firm

(e.g., Feng, Morgan, and Rego 2015) and, by at least indirect

extension, supports the notion that chief marketing officers

matter (e.g., Germann, Ebbes, and Grewal 2015) if these firm

managers are aligned in their understanding (levels and drivers)

of the customers’ satisfaction (Hult et al. 2016). The find ing that

stock returns on customer satisfaction do beat the market is

robust in that the 15-year time period studied (2000–2014)

should be long enough to eliminate sector bias as an explanation.

As an additional check, we also estimated models with different

benchmarks, especially for technolog y and industrial sectors.

The difference in overperformance was marginal whether we

used NASDAQ or the DJIA.

There is a statistically significant relationship between

customer satisfaction and lagged earnings surprises, and cus-

tomer satisfaction is largely without influence on contempora-

neous share prices until its effects are manifested in earnings

reports. Customer satisfaction also has an effect on earnings

thems el ves . P e rh ap s even more notabl e i s t he finding that

earnings returns have an effect on customer satisfaction returns.

When lagged earnings returns are included among the risk

factors, the abnormal returns on customer satisfaction are

reduced from 10.8% per annum to 8.4%.

Equation 1 alludes to the expectation of major abnormal

returns because (1) equity value, expressed as the discounted

net present value of future cash flows from current customers,

can increase greatly even with modest growth in customer

retention, and (2) investors in general do not seem to be aware

of this (see Gupta, Lehmann, and Stuart 2004). Because the

market does not generally value customer satisfaction until

its effects show up in improved company financials, it is

noteworthy that a marketing intangible can produce returns

much higher than many other types of intangibles, further

underscoring the conclusion that familiarity with marketing

information is not widely spread among equity market par-

ticipants. This may be particularly true with respect to the

huge leverage from loyal customers. For example, Gupta and

Lehmann (2005) find that a 1% improvement in customer

retention has an effect on customer equity value that is 5 times

greater than a comparable gain in profit margin and 50 times

TABLE 8

Average Returns and P/E Ratios

2011–2012 Avg. Ret. % 2012–2013 Avg. Ret. % 2011–2012 P/E Ratio 2012–2013 P/E Ratio

S&P 500 14.9% 23.2% 18.24 18.57

ACSI 17.2% 23.9% 15.72 18.25

Longs 15.5% 18.9% 17.64 19.24

S&P Top 100 9.7% 54.4% 14.26 18.25

ACSI Top 25 7.5% 65.9% 14.98 20.28

S&P Bottom 349 16.4% 13.6% 19.46 18.66

ACSI Bottom 111 19.8% 12.6% 15.92 17.71

Notes: Avg. Ret. % = average return percentage (source: Compustat); P/E Ratio = price-to-earnings ratio (source: Compustat). As in Table 6, “ S&P

500” = the total sample of 449 measures available during the period; “ACSI” = the 136 companies in the ACSI universe for which data were

available; “Longs” = the long positions within the satisfaction portfolio; “S&P Top 100” = top 100 performing companies in the S&P 500 (vs. the

“Bottom 349”); “ACSI Top 25” = top 25 performing companies in the ACSI (vs. the “Bottom 111”).

104 / Journal of Marketing, September 2016

greater than the same magnitude of improvement in cu stomer

acquisition cost.

The returns are so different from expected returns that it

might not be appropriate to label them as yet another asset

pricing anomaly. According to Fama and French (2008), all

stock return anomalies are proxies for intangibles and for