The OpenGL

®

ES Shading Language

Language Version: 1.00

Document Revision: 17

12 May, 2009

Editor: Robert J. Simpson

(Editor, version 1.00, revisions 1-11: John Kessenich)

ii

Copyright (c) 2006-2009 The Khronos Group Inc. All Rights Reserved.

This specification is protected by copyright laws and contains material proprietary to the Khronos Group,

Inc. It or any components may not be reproduced, republished, distributed, transmitted, displayed,

broadcast or otherwise exploited in any manner without the express prior written permission of Khronos

Group. You may use this specification for implementing the functionality herein, without altering or

removing any trademark, copyright or other notice from the specification, but the receipt or possession of

this specification does not convey any rights to reproduce, disclose, or distribute its contents, or to

manufacture, use, or sell anything that it may describe, in whole or in part.

Khronos Group grants express permission to any current Promoter, Contributor or Adopter member of

Khronos to copy and redistribute UNMODIFIED versions of this specification in any fashion, provided that

NO CHARGE is made for the specification and the latest available update of the specification for any

version of the API is used whenever possible. Such distributed specification may be re-formatted AS

LONG AS the contents of the specification are not changed in any way. The specification may be

incorporated into a product that is sold as long as such product includes significant independent work

developed by the seller. A link to the current version of this specification on the Khronos Group web-site

should be included whenever possible with specification distributions.

Khronos Group makes no, and expressly disclaims any, representations or warranties, express or implied,

regarding this specification, including, without limitation, any implied warranties of merchantability or

fitness for a particular purpose or non-infringement of any intellectual property. Khronos Group makes no,

and expressly disclaims any, warranties, express or implied, regarding the correctness, accuracy,

completeness, timeliness, and reliability of the specification. Under no circumstances will the Khronos

Group, or any of its Promoters, Contributors or Members or their respective partners, officers, directors,

employees, agents or representatives be liable for any damages, whether direct, indirect, special or

consequential damages for lost revenues, lost profits, or otherwise, arising from or in connection with

these materials.

Khronos is a trademark of The Khronos Group Inc. OpenGL is a registered trademark, and

OpenGL ES is a trademark, of Silicon Graphics, Inc.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

iii

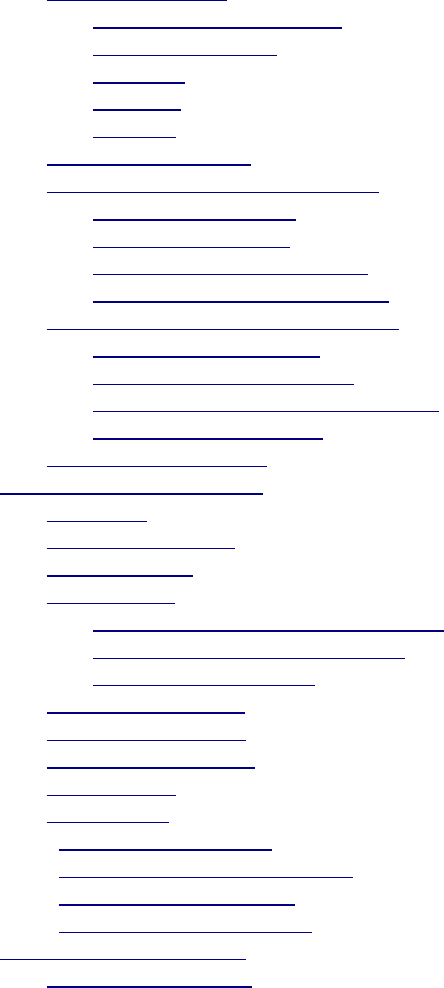

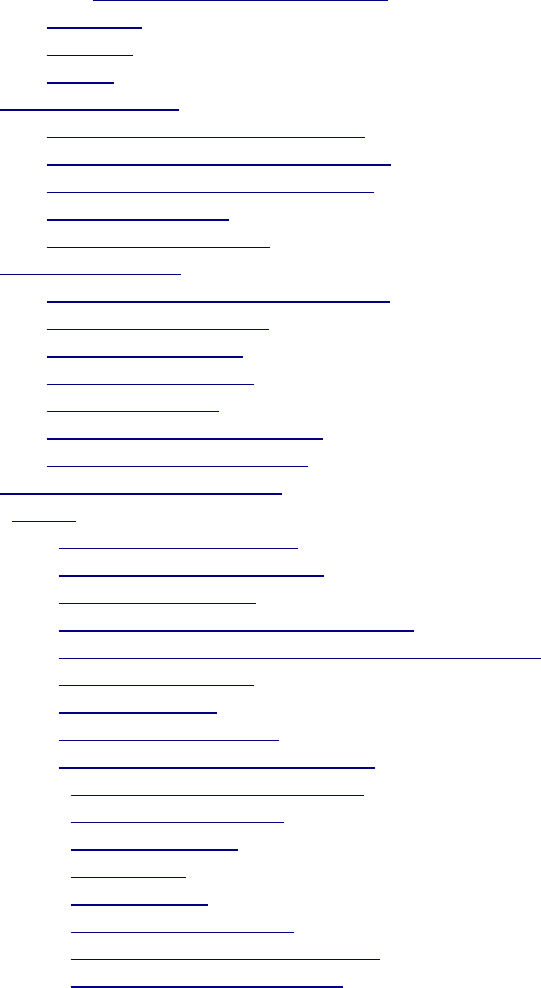

Table of Contents

1 Introduction................................................................................................................................1

1.1 Change History...................................................................................................................1

1.2 Overview............................................................................................................................6

1.3 Error Handling....................................................................................................................6

1.4 Typographical Conventions...............................................................................................7

2 Overview of OpenGL ES Shading.............................................................................................8

2.1 Vertex Processor................................................................................................................8

2.2 Fragment Processor............................................................................................................8

3 Basics.........................................................................................................................................9

3.1 Character Set......................................................................................................................9

3.2 Source Strings....................................................................................................................9

3.3 Logical Phases of compilation.........................................................................................10

3.4 Preprocessor.....................................................................................................................11

3.5 Comments........................................................................................................................15

3.6 Tokens..............................................................................................................................16

3.7 Keywords..........................................................................................................................16

3.8 Identifiers.........................................................................................................................17

4 Variables and Types.................................................................................................................18

4.1 Basic Types......................................................................................................................18

4.1.1 Void..........................................................................................................................19

4.1.2 Booleans...................................................................................................................19

4.1.3 Integers.....................................................................................................................19

4.1.4 Floats........................................................................................................................21

4.1.5 Vectors......................................................................................................................21

4.1.6 Matrices....................................................................................................................22

4.1.7 Samplers...................................................................................................................22

4.1.8 Structures..................................................................................................................22

4.1.9 Arrays.......................................................................................................................24

4.2 Scoping.............................................................................................................................25

4.2.1 Definition of Terms..................................................................................................25

4.2.2 Types of Scope.........................................................................................................25

4.2.3 Redeclaring Variables...............................................................................................26

4.2.4 Shared Globals..........................................................................................................26

4.2.5 Global Scope............................................................................................................27

4.2.6 Name spaces and Hiding..........................................................................................27

4.2.7 Redeclarations and Redefinitions Within the Same Scope......................................27

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

iv

4.3 Storage Qualifiers.............................................................................................................29

4.3.1 Default Storage Qualifier..........................................................................................29

4.3.2 Constant Qualifier....................................................................................................29

4.3.3 Attribute....................................................................................................................30

4.3.4 Uniform....................................................................................................................30

4.3.5 Varying.....................................................................................................................31

4.4 Parameter Qualifiers.........................................................................................................32

4.5 Precision and Precision Qualifiers...................................................................................32

4.5.1 Range and Precision.................................................................................................32

4.5.2 Precision Qualifiers..................................................................................................33

4.5.3 Default Precision Qualifiers.....................................................................................35

4.5.4 Available Precision Qualifiers..................................................................................36

4.6 Variance and the Invariant Qualifier................................................................................36

4.6.1 The Invariant Qualifier.............................................................................................37

4.6.2 Invariance Within Shaders........................................................................................38

4.6.3 Invariance of Constant Expressions.........................................................................39

4.6.4 Invariance and Linkage.............................................................................................39

4.7 Order of Qualification......................................................................................................39

5 Operators and Expressions.......................................................................................................40

5.1 Operators..........................................................................................................................40

5.2 Array Subscripting...........................................................................................................41

5.3 Function Calls..................................................................................................................41

5.4 Constructors.....................................................................................................................41

5.4.1 Conversion and Scalar Constructors........................................................................41

5.4.2 Vector and Matrix Constructors...............................................................................42

5.4.3 Structure Constructors..............................................................................................43

5.5 Vector Components..........................................................................................................44

5.6 Matrix Components..........................................................................................................45

5.7 Structures and Fields........................................................................................................46

5.8 Assignments.....................................................................................................................46

5.9 Expressions......................................................................................................................47

5.10 Constant Expressions.....................................................................................................49

5.11 Vector and Matrix Operations........................................................................................50

5.12 Precisions of operations.................................................................................................51

5.13 Evaluation of expressions..............................................................................................51

6 Statements and Structure..........................................................................................................52

6.1 Function Definitions.........................................................................................................53

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

v

6.1.1 Function Calling Conventions..................................................................................54

6.2 Selection...........................................................................................................................56

6.3 Iteration............................................................................................................................56

6.4 Jumps................................................................................................................................57

7 Built-in Variables.....................................................................................................................59

7.1 Vertex Shader Special Variables......................................................................................59

7.2 Fragment Shader Special Variables.................................................................................60

7.3 Vertex Shader Built-In Attributes....................................................................................61

7.4 Built-In Constants............................................................................................................61

7.5 Built-In Uniform State.....................................................................................................62

8 Built-in Functions....................................................................................................................63

8.1 Angle and Trigonometry Functions..................................................................................64

8.2 Exponential Functions......................................................................................................65

8.3 Common Functions..........................................................................................................66

8.4 Geometric Functions........................................................................................................68

8.5 Matrix Functions..............................................................................................................69

8.6 Vector Relational Functions.............................................................................................70

8.7 Texture Lookup Functions...............................................................................................71

9 Shading Language Grammar....................................................................................................73

10 Issues......................................................................................................................................84

10.1 Vertex Shader Precision.................................................................................................84

10.2 Fragment Shader Precision.............................................................................................84

10.3 Precision Qualifiers........................................................................................................84

10.4 Function and Variable Name Spaces..............................................................................88

10.5 Local Function Declarations and Function Hiding........................................................88

10.6 Overloading main()........................................................................................................88

10.7 Error Reporting..............................................................................................................88

10.8 Structure Declarations....................................................................................................89

10.9 Embedded Structure Definitions....................................................................................89

10.10 Redefining Built-in Functions......................................................................................90

10.11 Constant Expressions...................................................................................................90

10.12 Varying Linkage...........................................................................................................91

10.13 gl_Position....................................................................................................................91

10.14 Pre-processor................................................................................................................91

10.15 Phases of Compilation..................................................................................................92

10.16 Maximum Number of Varyings...................................................................................92

10.17 Unsized Array Declarations.........................................................................................93

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

vi

10.18 Invariance.....................................................................................................................94

10.19 Invariance Within a shader...........................................................................................95

10.20 While-loop Declarations..............................................................................................96

10.21 Cross Linking Between Shaders...................................................................................96

10.22 Visibility of Declarations.............................................................................................96

10.23 Language Version.........................................................................................................97

10.24 Samplers.......................................................................................................................97

10.25 Dynamic Indexing........................................................................................................97

10.26 Maximum Number of Texture Units............................................................................98

10.27 On-target Error Reporting............................................................................................98

10.28 Rounding of Integer Division.......................................................................................98

10.29 Undefined Return Values.............................................................................................98

10.30 Precisions of Operations...............................................................................................99

10.31 Compiler Transforms.................................................................................................100

10.32 Expansion of Function-like Macros in the Preprocessor...........................................100

10.33 Should Extension Macros be Globally Defined?.......................................................100

10.34 Increasing the Minimum Requirements.....................................................................101

11 Errors....................................................................................................................................103

11.1 Preprocessor Errors......................................................................................................103

11.2 Lexer/Parser Errors.......................................................................................................103

11.3 Semantic Errors............................................................................................................103

11.4 Linker

.................................................................................................................................................105

12 Normative References..........................................................................................................106

13 Acknowledgements..............................................................................................................107

Appendix A: Limitations for ES 2.0..........................................................................................108

1 Overview...........................................................................................................................108

2 Length of Shader Executable............................................................................................108

3 Usage of Temporary Variables..........................................................................................108

4 Control Flow.....................................................................................................................108

5 Indexing of Arrays, Vectors and Matrices.........................................................................109

6 Texture Accesses...............................................................................................................110

7 Counting of Varyings and Uniforms.................................................................................111

8 Shader Parameters.............................................................................................................113

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction

The OpenGL ES Shading Language (also known as GLSL ES or ESSL) is based on the OpenGL Shading

Language (GLSL) version 1.20. This document restates the relevant parts of the GLSL specification and

so is self-contained in this respect. However GLSL ES is also based on C++ (see section 12: Normative

References) and this reference must be used in conjunction with this document.

1.1 Change History

Changes from Revision 16 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Corrected grammar for statements with scope

• Clarified that scalars cannot be treated as single-component vectors.

• Extended minimum requirements for array indexing.

• Corrected behavior of #line directive.

Changes from Revision 15 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Behavior of logical operators in the preprocessor.

• Precision of arithmetic operations.

• Rules for compiler transforms of arithmetic expressions.

• Extension macros are defined before #extension.

• Support of high precision types in the fragment shader is an option, not an extension.

Changes from Revision 14 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Clarify void can be used to specify an empty actual parameter list.

• Assignments return r-values and not l-values.

• The term shader refers to the set of compilation units running on either the vertex or fragment

processor.

• Undefined operands in preprocessor expressions do not default to '0'

• Returning from a function with a non-void return type but without executing a return statement causes

an undefined value to be returned.

• Clarified scoping of variables declared within if statements.

Changes from Revision 13 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Clarified the order of evaluation of function parameters.

• Restrictions on the use of types and qualifiers also apply to structures that contain them.

1

1 Introduction 2

• Unsubscripted arrays are not allowed as parameters to constructors.

• Not writing to an out parameter in a function leaves that parameter undefined when the call returns.

• Added references section.

• gl_MaxVaryingFloats=32 changed to gl_MaxVaryingVectors=8.

• gl_MaxCombinedTextureImageUnits and gl_MaxTextureImageUnits changed from 2 to 8.

• Clarified that one function prototype is allowed for each function definition.

Changes from Revision 12 of the OpenGL ES shading Language specification:

• Added ES 2.0 minimum requirements section.

• Matrix constructors are allowed to take matrix parameters (unification with desktop GLSL).

• Precision qualifiers allowed on samplers.

• Invariant qualifier allowed on varying inputs to the fragment shader. Use must match use on varying

outputs from vertex shader. Clarified how built-in special variables can be qualified.

• Structure names are visible at the end of the struct_specifier.

• Clarify uniforms and varyings cannot have initializers.

• Move all extensions to separate extension specification.

• Clarified integer precision.

• Changed gl_MaxVertexUniformComponents to gl_MaxVertexUniformVectors.

• Changed gl_MaxFragmentUniformComponents to gl_MaxFragmentUniformVectors.

• Removed invariance within a shader (global flag means invariant within a shader as well).

• Moved built-ins back to outer level scope.

• Correction: lowp int cannot be represented by lowp float

• Increased vertex uniforms from 384 to 512 to take into account the inefficiencies of the packing

algorithm.

• Changed __VERSION__ to 100.

• The only shared globals in ES are uniforms. The precisions of varyings do not need to match.

• Defined gl_MaxVaryingFloats in terms of a packing algorithm.

• Defined gl_MaxUniformComponents in terms of the packing algorithm.

• Removed unsized array declarations.

• Defined compilation stages. Preprocessor runs after preprocessing tokens are generated.

• Removed embedded structure definitions.

• Prohibit cross linking between vertex and fragment shader/compilation unit.

• void cannot be used to declare a variable or structure element.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction 3

• Fixed function varyings count as part of the total when they are referenced by the fragment shader.

• Clarification of anonymous structures.

• ES allows only two compilation units, one for the vertex shader, one for the fragment shader.

• Static recursion must be detected by the compiler.

• Constant expressions must be invariant.

• Clarify when the compiler or linker must report errors.

• Unsubscripted arrays are l-value expressions but can only be used as actual parameters or within

parentheses.

• Constant expression can contain built-in functions.

• Constant expression can be an element of a vector or matrix.

• Clarify that arrays cannot be declared constant since there is no method to initialize them.

• Removed structure definitions from formal parameters.

• Removed the dual name space.

• Clarify allowing repeated declarations but disallow repeated definitions within the same scope.

• Disallow local function declarations.

• Remove the ability to redefine built-in functions (Simplification. Function not useful for ES).

Changes from Revision 11 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Added list of errors generated by the compiler.

• Specify no white space in floating point constants.

• Specify how struct constructors use the function name space.

• Prohibit main() function with other signatures.

• Clarify how functions are hidden by other functions.

• Specify that expressions where the precision cannot be defined must be evaluated at the default

precision

• Specify the rules for invariance within a shader.

Changes from Revision 10 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• The extensions' macros are defined to a value of '1', not just defined. This is to conform to the correct

convention.

Changes from Revision 9 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Added formal extension for noise functions.

• Added formal extension for derivative functions.

• Made 3D textures available only if the 3D texture extension is enabled. This is part of an API

extension.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction 4

Changes from Revision 8 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Added the grammar at the end.

• Correct multiple qualifier order, to match existing parameter qualification order.

• Refined invariant declarations: takes a list, is globally scoped, and declared before use.

• Make spec. references refer to the 2.0 OpenGL spec. instead of version 1.4.

• Removed gl_MaxTextureUnits, as it is for fixed function only.

• Removed comment about point sprites being disabled.

• Reserved 'superp' for possible future super precision qualifier.

• Gave specific precision qualifiers to the built-in variables in section 7.

• Added a note in the built-in functions (chapter 8) about precision qualification for parameters and

return values.

Changes from Revision 7 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Added actual ranges and precisions.

• Stated what happens on floating point overflow.

• Change intermediate results precision to be based on operands' precision when possible, and not to

include the l-values' precision.

• Add the macro GL_ES to test for compilation for an ES system.

• Allow out of bounds array access behavior to be platform dependent.

Changes from Revision 6 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Added precision qualifiers highp, mediump, and lowp for floating point and integer types.

• Added invariant qualifier to say an output value is to be invariant. Remove the specific mechanism

itransform().

• Grammar was deleted, to be replaced later with correct ES grammar.

Changes from Revision 5 of the OpenGL ES Shading Language specification:

• Fixed a lot of typos and English-level clarifications. Same typos were fixed in Revision 59 of the

OpenGL Shading Language specification to form Revision 60. These shared non-functional changes

are not identified with change bars or other markings.

Changes from Revision 59 of the OpenGL Shading Language specification:

• Most OpenGL state uniform variables are removed.

• All OpenGL state attribute variables are removed.

• All OpenGL state varying variables are removed.

• The output variables gl_ClipVertex and gl_FragDepth are removed.

• Point sprites are supported with the added built-in gl_PointCoord varying variable.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction 5

• The minimum maximum vertex attributes is changed from 16 to 8, the minimum maximum vertex-

uniform-components is changed from 512 to 384.

• Removed 1D and shadow textures.

• Proposed precision hints and minimum precisions are specified.

• Generic itransform() is added to replace the removed fix-functionality ftransform().

• dFdx(), dFdy(), and fwidth() are made optional.

• noise() is made optional.

• Other minor language fixes/simplifications. Static recursion is disallowed (dynamic recursion was

already disallowed). Error messages can be skipped. Behavior for writing outside an array is limited.

clamp() and smoothstep() domain descriptions are improved.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction 6

1.2 Overview

This document describes The OpenGL ES Shading Language.

The OpenGL ES pipeline contains a programmable vertex stage and a programmable fragment stage. The

remaining stages are referred to as fixed function and the application has only limited control over their

behavior. The set of compilation units for each programmable stage form a shader. OpenGL ES 2.0 only

supports a single compilation unit per shader.

A program is a complete set of shaders that are compiled and linked together. The aim of this document

is to thoroughly specify the programming language. The entry points used to manipulate and

communicate with programs and shaders are defined in a separate specification.

Implementations of GLSL ES 2.0 are further restricted as described in Appendix A.

1.3 Error Handling

Compilers, in general, accept programs that are ill-formed, due to the impossibility of detecting all ill-

formed programs. Portability is only ensured for well-formed programs, which this specification

describes. Compilers are encouraged to detect ill-formed programs and issue diagnostic messages, but are

not required to do so for all cases. Either the compiler or the linker is required to reject lexically or

grammatically incorrect shaders. Some semantic errors must also be detected and reported as indicated in

the specification.

Where the specification uses the terms required, must/must not, does/does not, disallowed or not

supported, the compiler or linker is required to detect and report any violations. Similarly when a

condition or situation is an error, it must be reported. Where the specification uses the terms

should/should not or undefined behavior there is no such requirement but compilers are encouraged to

report possible violations.

A distinction is made between undefined behavior and an undefined value (or result). Undefined

behavior includes system instability and/or termination of the application. It is expected that systems will

be designed to handle these cases gracefully but specification of this is outside the scope of OpenGL ES.

If a value or result is undefined, the system may behave as if the value or result had been assigned a

random value. For example, an undefined gl_Position may cause a triangle to be drawn with a random

size and position. The implementation may also detect the generation and/or use of undefined values and

behave accordingly (for example causing a trap). Undefined values must not by themselves cause system

instability. However undefined values may lead to other more serious conditions such as infinite loops or

out of bounds array accesses.

Implementations may not in general support functionality beyond the mandated parts of the specification

without use of the relevant extension. The only exceptions are:

1. If a feature is marked as optional.

2. Where a maximum values is stated (e.g. the maximum number of varyings). the implementation

may support a higher value than that specified.

Where the implementation supports more than the mandated specification, off-target compilers are

encouraged to issue warnings if these features are used.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

1 Introduction 7

The compilation process is split between the compiler and linker. The allocation of tasks between the

compiler and linker is implementation dependent. Consequently there are many errors which may be

detected either at compiler or link time, depending on the implementation.

1.4 Typographical Conventions

Italic, bold, and font choices have been used in this specification primarily to improve readability. Code

fragments use a fixed width font. Identifiers embedded in text are italicized. Keywords embedded in text

are bold. Operators are called by their name, followed by their symbol in bold in parentheses. The

clarifying grammar fragments in the text use bold for literals and italics for non-terminals. The official

grammar in Section 9 “Shading Language Grammar” uses all capitals for terminals and lower case for

non-terminals.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

2 Overview of OpenGL ES Shading

The OpenGL ES Shading Language is actually two closely related languages. These languages are used

to create shaders for the programmable processors contained in the OpenGL ES processing pipeline.

Unless otherwise noted in this paper, a language feature applies to all languages, and common usage will

refer to these languages as a single language. The specific languages will be referred to by the name of

the processor they target: vertex or fragment.

Any OpenGL ES state used by the shader is automatically tracked and made available to shaders. This

automatic state tracking mechanism allows the application to use OpenGL ES state commands for state

management and have the current values of such state automatically available for use in a shader.

2.1 Vertex Processor

The vertex processor is a programmable unit that operates on incoming vertices and their associated data.

Source code that is compiled and run on this processor forms a vertex shader.

A vertex shader operates on one vertex at a time. The vertex processor does not replace graphics

operations that require knowledge of several vertices at a time.

2.2 Fragment Processor

The fragment processor is a programmable unit that operates on fragment values and their associated

data. Source code that is compiled and run on this processor forms a fragment shader.

A fragment shader cannot change a fragment's position. Access to neighboring fragments is not allowed.

The values computed by the fragment shader are ultimately used to update frame-buffer memory or

texture memory, depending on the current OpenGL ES state and the OpenGL ES command that caused

the fragments to be generated.

8

3 Basics

3.1 Character Set

The source character set used for the OpenGL ES shading languages is a subset of ASCII (see section 12:

“Normative References“). It includes the following characters:

The letters a-z, A-Z, and the underscore ( _ ).

The numbers 0-9.

The symbols period (.), plus (+), dash (-), slash (/), asterisk (*), percent (%), angled brackets (< and

>), square brackets ( [ and ] ), parentheses ( ( and ) ), braces ( { and } ), caret (^), vertical bar ( | ),

ampersand (&), tilde (~), equals (=), exclamation point (!), colon (:), semicolon (;), comma (,), and

question mark (?).

The number sign (#) for preprocessor use.

White space: the space character, horizontal tab, vertical tab, form feed, carriage-return, and line-

feed.

Lines are relevant for compiler diagnostic messages and the preprocessor. They are terminated by

carriage-return or line-feed. If both are used together, it will count as only a single line termination. For

the remainder of this document, any these combinations is simply referred to as a new-line.

The line continuation character (\) is not part of the language.

In general, the language’s use of this character set is case sensitive.

There are no character or string data types, so no quoting characters are included.

There is no end-of-file character. The end of a source string is indicated to the compiler by a length, not a

character.

3.2 Source Strings

The source for a single compilation unit is an array of strings of characters from the character set. A

single compilation unit is made from the concatenation of these strings. Each string can contain multiple

lines, separated by new-lines. No new-lines need be present in a string; a single line can be formed from

multiple strings. No new-lines or other characters are inserted by the implementation when the strings are

concatenated. Vertex and fragment shaders each consist of a single compilation unit. A single vertex

shader and a single fragment shader are linked together to form a single program.

Diagnostic messages returned from compilation must identify both the line number within a string and

which source string the message applies to. Source strings are counted sequentially with the first string

being string 0. Line numbers are one more than the number of new-lines that have been processed.

9

3 Basics 10

For this version of the OpenGL ES Shading Language, each shader consists of a single compilation unit.

The architecture of the system and this specification are designed to link together multiple compilation

units for each shader, but this will not be supported until a future version of the specification.

3.3 Logical Phases of compilation

The compilation process is based on a subset of the c++ standard (see section 12: Normative References).

The compilation units for the vertex and fragment processor are processed separately before being linked

together in the final stage of compilation. The logical phases of compilation are:

1. Source strings are concatenated.

2. The source string is converted into a sequence of preprocessing tokens. These tokens include

preprocessing numbers, identifiers and preprocessing operations. Comments are each replaced

by one space character. Line breaks are retained.

3. The preprocessor is run. Directives are executed and macro expansion is performed.

4. Preprocessing tokens are converted into tokens.

5. White space and line breaks are discarded.

6. The syntax is analyzed according to the GLSL ES grammar.

7. The result is checked according to the semantic rules of the language.

8. The vertex and fragment shaders are linked together. Any varyings not used in both the vertex

and fragment shaders may be discarded.

9. The binary is generated.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 11

3.4 Preprocessor

There is a preprocessor that processes the source strings as part of the compilation process.

The complete list of preprocessor directives is as follows.

#

#define

#undef

#if

#ifdef

#ifndef

#else

#elif

#endif

#error

#pragma

#extension

#version

#line

The following operators are also available

defined

Each number sign (#) can be preceded in its line only by spaces or horizontal tabs. It may also be

followed by spaces and horizontal tabs, preceding the directive. Each directive is terminated by a new-

line. Preprocessing does not change the number or relative location of new-lines in a source string.

The number sign (#) on a line by itself is ignored. Any directive not listed above will cause a diagnostic

message and make the implementation treat the shader as ill-formed.

#define and #undef functionality are defined as for C++, for macro definitions both with and without

macro parameters.

The following predefined macros are available

__LINE__

__FILE__

__VERSION__

GL_ES

__LINE__ will substitute a decimal integer constant that is one more than the number of preceding new-

lines in the current source string.

__FILE__ will substitute a decimal integer constant that says which source string number is currently

being processed.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 12

__VERSION__ will substitute a decimal integer reflecting the version number of the OpenGL ES shading

language. The version of the shading language described in this document will have __VERSION__

substitute the decimal integer 100.

GL_ES will be defined and set to 1. This is not true for the non-ES OpenGL Shading Language, so it can

be used to do a compile time test to see whether a shader is running on ES system.

All macro names containing two consecutive underscores ( __ ) are reserved for future use as predefined

macro names. All macro names prefixed with “GL_” (“GL” followed by a single underscore) are also

reserved.

#if, #ifdef, #ifndef, #else, #elif, and #endif are defined to operate as for C++ except for the following:

• Expressions following #if and #elif are restricted to expressions operating on literal integer

constants, plus identifiers consumed by the defined operator.

• Undefined identifiers not consumed by the defined operator do not default to '0'. Use of such

identifiers causes an error.

• Character constants are not supported.

The operators available are as follows.

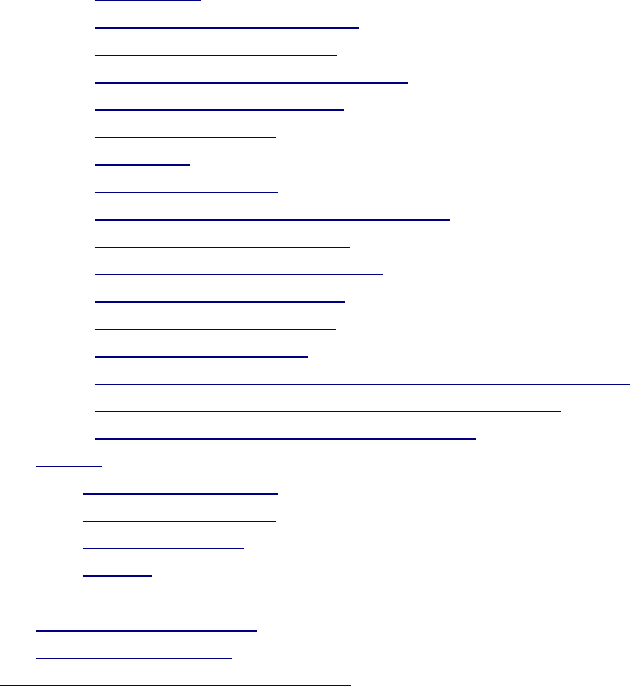

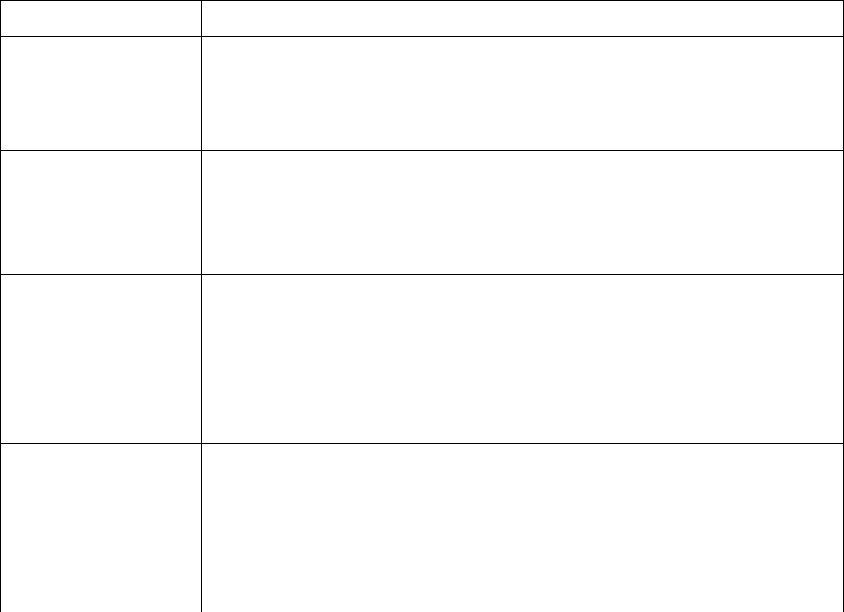

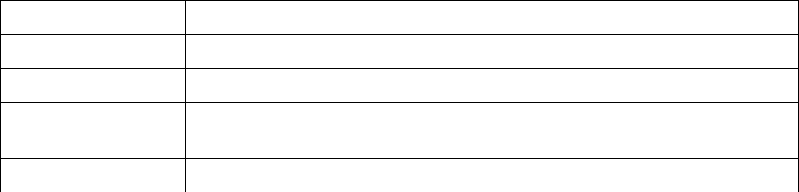

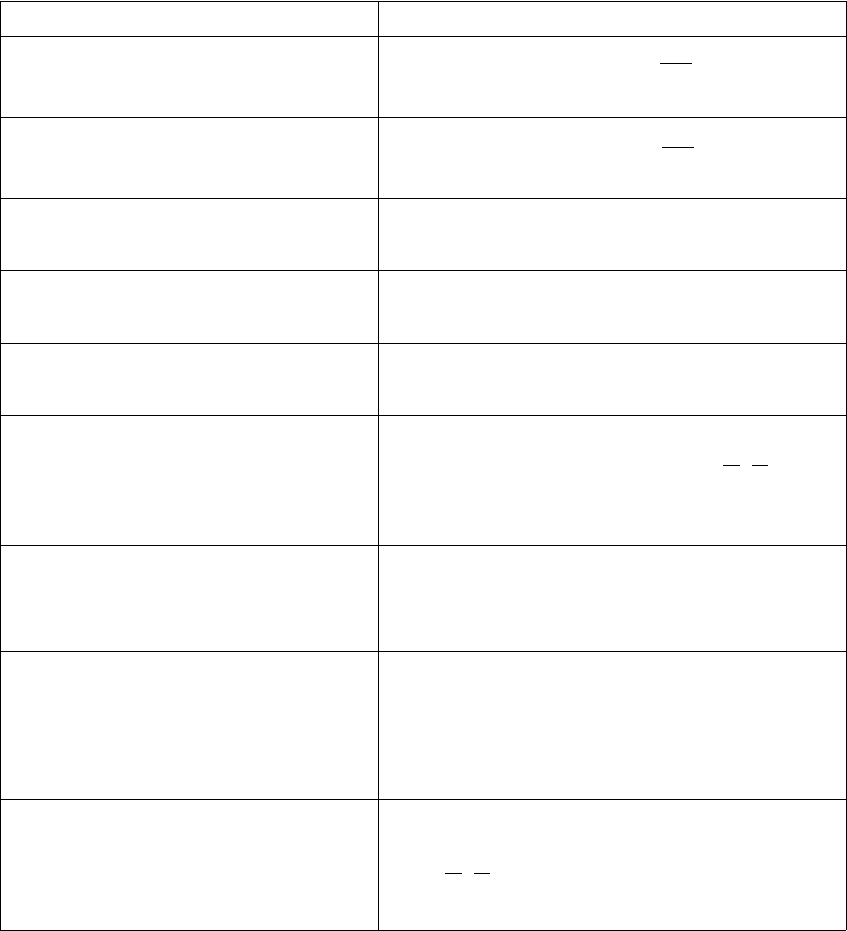

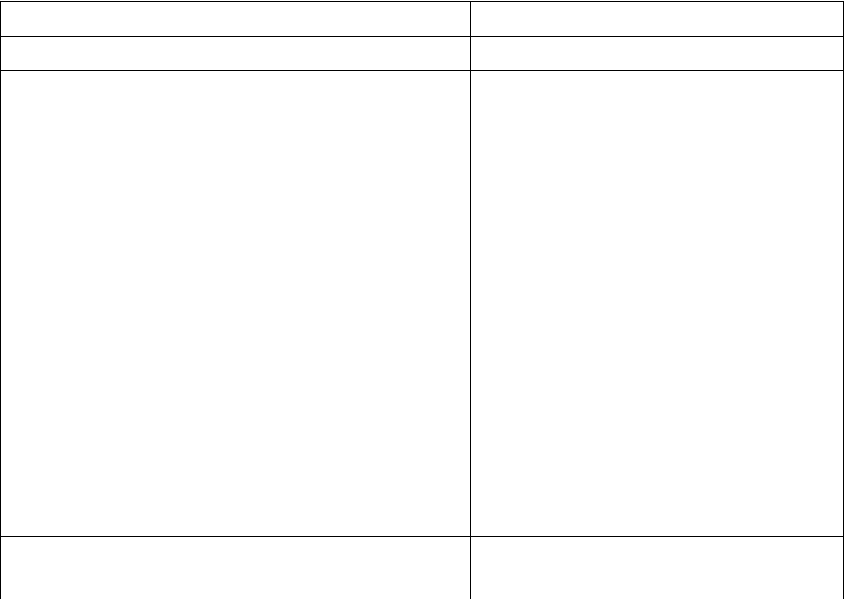

Precedence Operator class Operators Associativity

1 (highest) parenthetical grouping ( ) NA

2 unary defined

+ - ~ !

Right to Left

3 multiplicative * / % Left to Right

4 additive + - Left to Right

5 bit-wise shift << >> Left to Right

6 relational < > <= >= Left to Right

7 equality == != Left to Right

8 bit-wise and & Left to Right

9 bit-wise exclusive or ^ Left to Right

10 bit-wise inclusive or | Left to Right

11 logical and && Left to Right

12 (lowest) logical inclusive or | | Left to Right

The defined operator can be used in either of the following ways:

defined identifier

defined ( identifier )

There are no number sign based operators (no #, #@, ##, etc.), nor is there a sizeof operator.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 13

The semantics of applying operators in the preprocessor match those standard in the C++ preprocessor

with the following exceptions:

• The 2

nd

operand in a logical and ('&&') operation is evaluated if and only if the 1

st

operand

evaluates to non-zero.

• The 2

nd

operand in a logical or ('||') operation is evaluated if and only if the 1

st

operand evaluates

to zero.

If an operand is not evaluated, the presence of undefined identifiers in the operand will not cause an error.

Preprocessor expressions will be evaluated at compile time.

#error will cause the implementation to put a diagnostic message into the shader object’s information log

(see the API in the platform documentation for how to access a shader object’s information log). The

message will be the tokens following the #error directive, up to the first new-line. The implementation

must then consider the shader to be ill-formed.

#pragma allows implementation dependent compiler control. Tokens following #pragma are not subject

to preprocessor macro expansion. If an implementation does not recognize the tokens following

#pragma, then it will ignore that pragma. The following pragmas are defined as part of the language.

#pragma STDGL

The STDGL pragma is used to reserve pragmas for use by future revisions of this language. No

implementation may use a pragma whose first token is STDGL.

#pragma optimize(on)

#pragma optimize(off)

can be used to turn off optimizations as an aid in developing and debugging shaders. It can only be used

outside function definitions. By default, optimization is turned on for all shaders. The debug pragma

#pragma debug(on)

#pragma debug(off)

can be used to enable compiling and annotating a shader with debug information, so that it can be used

with a debugger. It can only be used outside function definitions. By default, debug is turned off.

Each compilation unit should declare the version of the language it is written to using the #version

directive:

#version number

where number must be 100 for this specification’s version of the language (following the same convention

as __VERSION__ above), in which case the directive will be accepted with no errors or warnings. Any

number less than 100 will cause an error to be generated. Any number greater than the latest version of

the language a compiler supports will also cause an error to be generated. Version 100 of the language

does not require compilation units to include this directive, and compilation units that do not include a

#version directive will be treated as targeting version 100.

The #version directive must occur in a compilation unit before anything else, except for comments and

white space.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 14

By default, compilers of this language must issue compile time syntactic, grammatical, and semantic

errors for compilation units that do not conform to this specification. Any extended behavior must first be

enabled. Directives to control the behavior of the compiler with respect to extensions are declared with

the #extension directive

#extension extension_name : behavior

#extension all : behavior

where extension_name is the name of an extension. Extension names are not documented in this

specification. The token all means the behavior applies to all extensions supported by the compiler. The

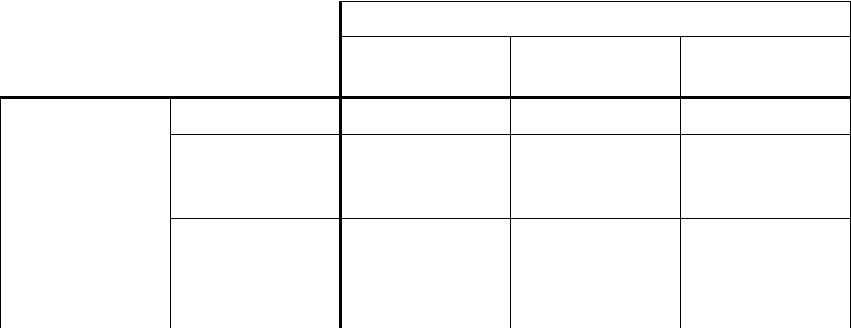

behavior can be one of the following

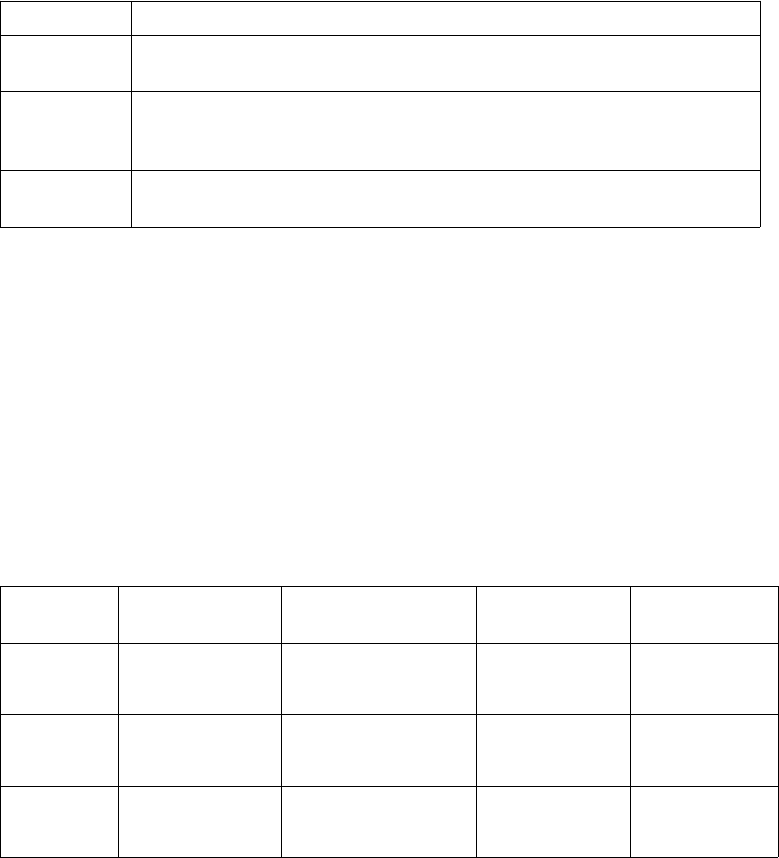

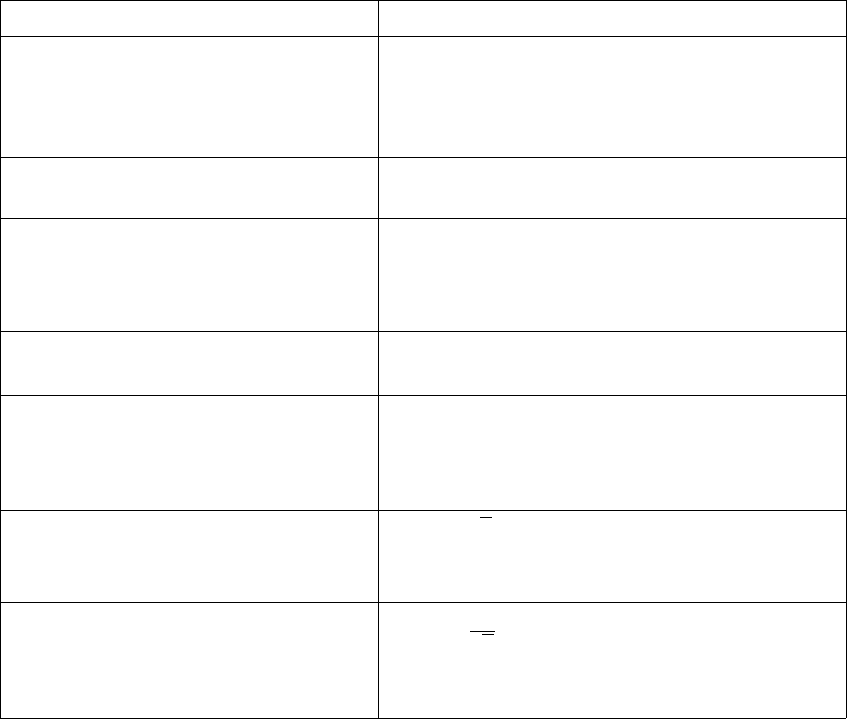

behavior Effect

require

Behave as specified by the extension extension_name.

Give an error on the #extension if the extension extension_name is not

supported, or if all is specified.

enable

Behave as specified by the extension extension_name.

Warn on the #extension if the extension extension_name is not supported.

Give an error on the #extension if all is specified.

warn

Behave as specified by the extension extension_name, except issue warnings

on any detectable use of that extension, unless such use is supported by other

enabled or required extensions.

If all is specified, then warn on all detectable uses of any extension used.

Warn on the #extension if the extension extension_name is not supported.

disable

Behave (including issuing errors and warnings) as if the extension

extension_name is not part of the language definition.

If all is specified, then behavior must revert back to that of the non-extended

core version of the language being compiled to.

Warn on the #extension if the extension extension_name is not supported.

The extension directive is a simple, low-level mechanism to set the behavior for each extension. It does

not define policies such as which combinations are appropriate, those must be defined elsewhere. The

order of directives matters in setting the behavior for each extension: directives that occur later override

those seen earlier. The all variant sets the behavior for all extensions, overriding all previously issued

extension directives, but only for the behaviors warn and disable.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 15

The initial state of the compiler is as if the directive

#extension all : disable

was issued, telling the compiler that all error and warning reporting must be done according to this

specification, ignoring any extensions.

Each extension can define its allowed granularity of scope. If nothing is said, the granularity is a single

compilation unit, and the extension directives must occur before any non-preprocessor tokens. If

necessary, the linker can enforce granularities larger than a single compilation unit, in which case each

involved compilation unit will have to contain the necessary extension directive.

Macro expansion is not done on lines containing #extension and #version directives.

For each extension there is an associated macro. The macro is always defined in an implementation that

supports the extension. This allows the following construct to be used:

#ifdef OES_extension_name

#extension OES_extension_name : enable

// code that requires the extension

#else

// alternative code

#endif

#line must have, after macro substitution, one of the following two forms:

#line line

#line line source-string-number

where line and source-string-number are constant integer expressions. After processing this directive

(including its new-line), the implementation will behave as if the following line has line number line and

starts with source string number source-string-number. Subsequent source strings will be numbered

sequentially, until another #line directive overrides that numbering.

If during macro expansion a preprocessor directive is encountered, the results are undefined. The

compiler may or may not report an error in such cases.

3.5 Comments

Comments are delimited by /* and */, or by // and a new-line. The begin comment delimiters (/* or //) are

not recognized as comment delimiters inside of a comment, hence comments cannot be nested. If a

comment resides entirely within a single line, it is treated syntactically as a single space. New-lines are

not eliminated by comments.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 16

3.6 Tokens

The language is a sequence of tokens. A token can be

token:

keyword

identifier

integer-constant

floating-constant

operator

3.7 Keywords

The following are the keywords in the language, and cannot be used for any other purpose than that

defined by this document:

attribute const uniform varying

break continue do for while

if else

in out inout

float int void bool true false

lowp mediump highp precision invariant

discard return

mat2 mat3 mat4

vec2 vec3 vec4 ivec2 ivec3 ivec4 bvec2 bvec3 bvec4

sampler2D samplerCube

struct

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

3 Basics 17

The following are the keywords reserved for future use. Using them will result in an error:

asm

class union enum typedef template this packed

goto switch default

inline noinline volatile public static extern external interface flat

long short double half fixed unsigned superp

input output

hvec2 hvec3 hvec4 dvec2 dvec3 dvec4 fvec2 fvec3 fvec4

sampler1D sampler3D

sampler1DShadow sampler2DShadow

sampler2DRect sampler3DRect sampler2DRectShadow

sizeof cast

namespace using

In addition, all identifiers containing two consecutive underscores (__) are reserved as possible future

keywords.

3.8 Identifiers

Identifiers are used for variable names, function names, structure names, and field selectors (field

selectors select components of vectors and matrices similar to structure fields, as discussed in Section 5.5

“Vector Components” and Section 5.6 “Matrix Components” ). Identifiers have the form

identifier

nondigit

identifier nondigit

identifier digit

nondigit: one of

_ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

digit: one of

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Identifiers starting with “gl_” are reserved for use by OpenGL ES. No user-defined identifiers may begin

with “gl_”.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types

All variables and functions must be declared before being used. Variable and function names are

identifiers.

There are no default types. All variable and function declarations must have a declared type, and

optionally qualifiers. A variable is declared by specifying its type followed by one or more names

separated by commas. In many cases, a variable can be initialized as part of its declaration by using the

assignment operator (=). The grammar near the end of this document provides a full reference for the

syntax of declaring variables.

User-defined types may be defined using struct to aggregate a list of existing types into a single name.

The OpenGL ES Shading Language is type safe. There are no implicit conversions between types.

4.1 Basic Types

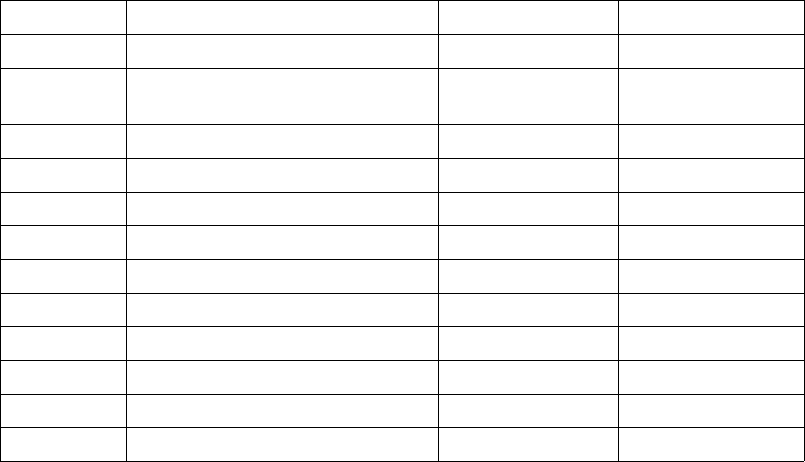

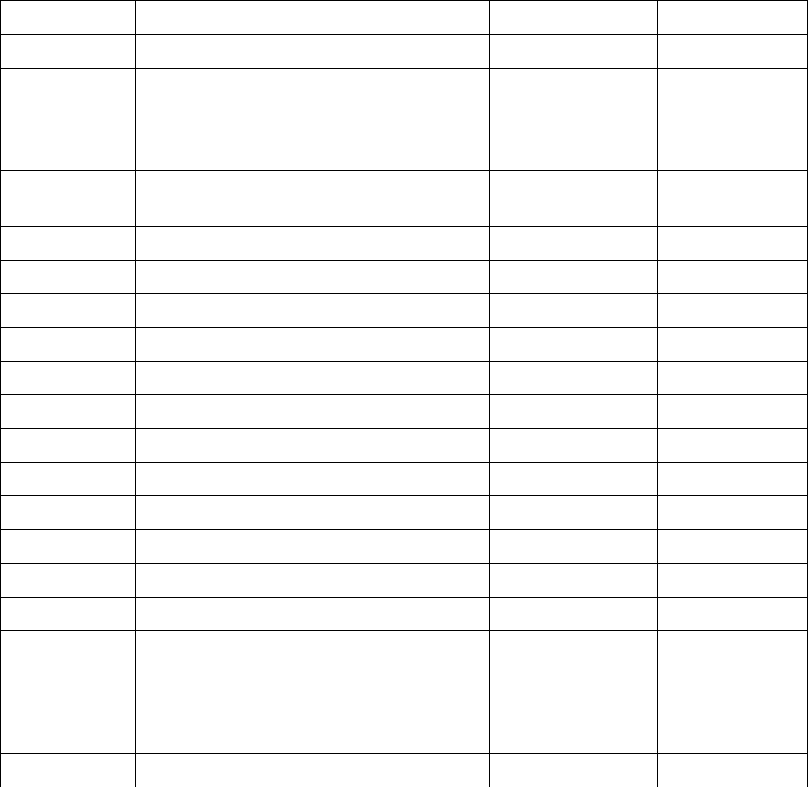

The OpenGL ES Shading Language supports the following basic data types.

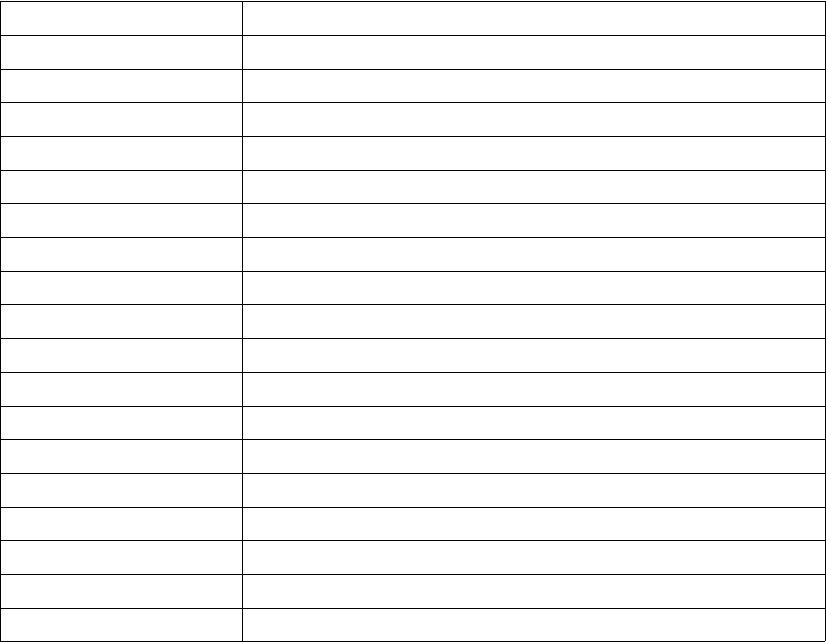

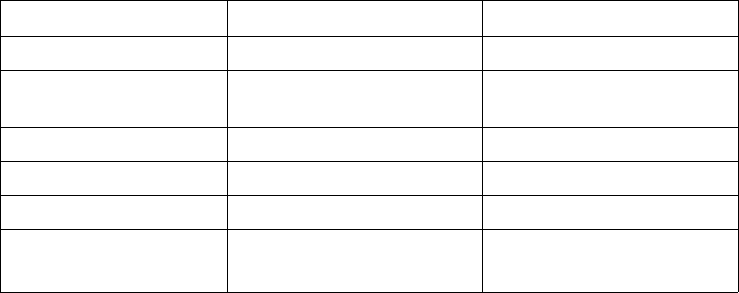

Type Meaning

void

for functions that do not return a value or for an empty parameter list

bool

a conditional type, taking on values of true or false

int

a signed integer

float

a single floating-point scalar

vec2

a two component floating-point vector

vec3

a three component floating-point vector

vec4

a four component floating-point vector

bvec2

a two component Boolean vector

bvec3

a three component Boolean vector

bvec4

a four component Boolean vector

ivec2

a two component integer vector

ivec3

a three component integer vector

ivec4

a four component integer vector

mat2

a 2×2 floating-point matrix

mat3

a 3×3 floating-point matrix

mat4

a 4×4 floating-point matrix

sampler2D

a handle for accessing a 2D texture

samplerCube

a handle for accessing a cube mapped texture

18

4 Variables and Types 19

In addition, a shader can aggregate these using arrays and structures to build more complex types.

There are no pointer types.

4.1.1 Void

The void type may only be used as a function return type or as an empty formal or actual parameter list.

4.1.2 Booleans

To make conditional execution of code easier to express, the type bool is supported. There is no

expectation that hardware directly supports variables of this type. It is a genuine Boolean type, holding

only one of two values meaning either true or false. Two keywords true and false can be used as Boolean

constants. Booleans are declared and optionally initialized as in the follow example:

bool success; // declare “success” to be a Boolean

bool done = false; // declare and initialize “done”

The right side of the assignment operator ( = ) can be any expression whose type is bool.

Expressions used for conditional jumps (if, for, ?:, while, do-while) must evaluate to the type bool.

4.1.3 Integers

Integers are mainly supported as a programming aid. At the hardware level, real integers would aid

efficient implementation of loops and array indices, and referencing texture units. However, there is no

requirement that integers in the language map to an integer type in hardware. It is not expected that

underlying hardware has full support for a wide range of integer operations. An OpenGL ES Shading

Language implementation may convert integers to floats to operate on them. Hence, there is no portable

wrapping behavior.

Integers are declared and optionally initialized with integer expressions as in the following example:

int i, j = 42;

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 20

Literal integer constants can be expressed in decimal (base 10), octal (base 8), or hexadecimal (base 16)

as follows.

integer-constant :

decimal-constant

octal-constant

hexadecimal-constant

decimal-constant :

nonzero-digit

decimal-constant digit

octal-constant :

0

octal-constant octal-digit

hexadecimal-constant :

0x hexadecimal-digit

0X hexadecimal-digit

hexadecimal-constant hexadecimal-digit

digit :

0

nonzero-digit

nonzero-digit : one of

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

octal-digit : one of

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

hexadecimal-digit : one of

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

a b c d e f

A B C D E F

No white space is allowed between the digits of an integer constant, including after the leading 0 or after

the leading 0x or 0X of a constant. A leading unary minus sign (-) is interpreted as an arithmetic unary

negation, not as part of the constant. There are no letter suffixes.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 21

4.1.4 Floats

Floats are available for use in a variety of scalar calculations. Floating-point variables are defined as in

the following example:

float a, b = 1.5;

Treatment of conditions such as divide by 0 may lead to an unspecified result, but must not lead to the

interruption or termination of processing.

Floating-point constants are defined as follows.

floating-constant :

fractional-constant exponent-part

opt

digit-sequence exponent-part

fractional-constant :

digit-sequence . digit-sequence

digit-sequence .

. digit-sequence

exponent-part :

e sign

opt

digit-sequence

E sign

opt

digit-sequence

sign : one of

+ –

digit-sequence :

digit

digit-sequence digit

A decimal point ( . ) is not needed if the exponent part is present. No white space is allowed between the

characters in a floating point constant. A leading unary minus sign (-) is interpreted as a unary operator

and is not part of the constant.

4.1.5 Vectors

The OpenGL ES Shading Language includes data types for generic 2-, 3-, and 4-component vectors of

floating-point values, integers, or Booleans. Floating-point vector variables can be used to store a variety

of things that are very useful in computer graphics: colors, normals, positions, texture coordinates, texture

lookup results and the like. Boolean vectors can be used for component-wise comparisons of numeric

vectors. Defining vectors as part of the shading language allows for direct mapping of vector operations

on graphics hardware that is capable of doing vector processing. In general, applications will be able to

take better advantage of the parallelism in graphics hardware by doing computations on vectors rather

than on scalar values. Some examples of vector declaration are:

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 22

vec2 texcoord1, texcoord2;

vec3 position;

vec4 myRGBA;

ivec2 textureLookup;

bvec3 lessThan;

Initialization of vectors can be done with constructors, which are discussed shortly.

4.1.6 Matrices

Matrices are another useful data type in computer graphics, and the OpenGL ES Shading Language

defines support for 2×2, 3×3, and 4×4 matrices of floating point numbers. Matrices are read from and

written to in column major order. Example matrix declarations:

mat2 mat2D;

mat3 optMatrix;

mat4 view, projection;

Initialization of matrix values is done with constructors (described in Section 5.4 “Constructors” ).

4.1.7 Samplers

Sampler types (e.g. sampler2D) are effectively opaque handles to textures. They are used with the built-

in texture functions (described in Section 8.7 “Texture Lookup Functions” ) to specify which texture to

access. They can only be declared as function parameters or uniforms (see Section 4.3.5 “Uniform” ).

Except for parameters to texture lookup functions, array indexing, structure field selection, and

parentheses, samplers are not allowed to be operands in expressions. Samplers cannot be treated as l-

values and cannot be used as out or inout function parameters. These restrictions also apply to any

structures that contain sampler types. As uniforms, they are initialized with the OpenGL ES API. As

function parameters, only samplers may be passed to samplers of matching type. This enables consistency

checking between shader texture accesses and OpenGL ES texture state before a shader is run.

4.1.8 Structures

User-defined types can be created by aggregating other already defined types into a structure using the

struct keyword. For example,

struct light {

float intensity;

vec3 position;

} lightVar;

In this example, light becomes the name of the new type, and lightVar becomes a variable of type light.

To declare variables of the new type, use its name (without the keyword struct).

light lightVar2;

More formally, structures are declared as follows. However, the complete correct grammar is as given in

Section 9 “Shading Language Grammar” .

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 23

struct-definition :

qualifiers

opt

struct name

opt

{ member-list } declarators

opt

;

member-list :

member-declaration;

member-declaration member-list;

member-declaration :

basic-type declarators;

where name becomes the user-defined type, and can be used to declare variables to be of this new type.

The name shares the same name space as other variables, types and functions. All previously visible

variables, types, constructors or functions with that name are hidden. The optional qualifiers only apply

to any declarators, and are not part of the type being defined for name.

Structures must have at least one member declaration. Member declarators may contain precision

qualifiers, but may not contain any other qualifiers. Bit fields are not supported. Member types must

already be defined (there are no forward references and no embedded definitions). Member declarations

cannot contain initializers. Member declarators can contain arrays. Such arrays must have a size

specified, and the size must be an integral constant expression that's greater than zero (see Section 4.3.3

“Integral Constant Expressions” ). Each level of structure has its own name space for names given in

member declarators; such names need only be unique within that name space.

Anonymous structure declarators (member declaration whose type is a structure but has no declarator) are

not supported.

struct S

{

int x;

};

struct T

{

S; // Error: anonymous structures are disallowed.

int y;

};

Embedded structure definitions are not supported:

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 24

Example 1:

struct S

{

struct T // error: embedded structure definition is not supported.

{

int a;

} t;

int b:

};

Example 2:

struct T

{

int a;

};

struct S

{

T t; // ok.

int b;

};

Structures can be initialized at declaration time using constructors, as discussed in Section 5.4.3

“Structure Constructors” .

Any restrictions on the usage of a type or qualifier also apply to a structure that contains that type or

qualifier. This applies recursively.

4.1.9 Arrays

Variables of the same type can be aggregated into arrays by declaring a name followed by brackets ( [ ] )

enclosing a size. The array size must be an integral constant expression (see Section 4.3.3 “Integral

Constant Expressions” ) greater than zero. It is illegal to index an array with an integral constant

expression greater than or equal to its declared size. It is also illegal to index an array with a negative

constant expression. Arrays declared as formal parameters in a function declaration must specify a size.

Only one-dimensional arrays may be declared. All basic types and structures can be formed into arrays.

Some examples are:

float frequencies[3];

uniform vec4 lightPosition[4];

const int numLights = 2;

light lights[numLights];

There is no mechanism for initializing arrays at declaration time from within a shader.

Reading from or writing to an array with a non-constant index that is less than zero or greater than or

equal to the array's size results in undefined behavior. It is platform dependent how bounded this

undefined behavior may be. It is possible that it leads to instability of the underlying system or corruption

of memory. However, a particular platform may bound the behavior such that this is not the case.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 25

4.2 Scoping

The scope of a declaration determines where the declaration is visible. GLSL ES uses a system of

statically nested scopes. This allows names to be redefined within a shader.

4.2.1 Definition of Terms

The term scope refers to a specified region of the program where names may be defined and are

guaranteed to be visible. For example, a compound_statement_with_scope ('{' statement statement ... '}')

defines a scope.

A nested scope is a scope defined within an outer scope.

The terms 'same scope' and 'current scope' are equivalent to the term 'scope' but used to emphasize that

nested scopes are excluded.

The scope of a definition is the region or regions of the program where that declaration is visible.

4.2.2 Types of Scope

The scope of a name is determined by where it is declared. If it is declared outside all function

definitions, it has global scope, which starts from where it is declared and persists to the end of the

compilation unit it is declared in. If it is declared in a while test or a for statement, then it is scoped to the

end of the following statement-no-new-scope. Otherwise, if it is declared as a statement within a

compound statement, it is scoped to the end of that compound statement. If it is declared as a parameter

in a function definition, it is scoped until the end of that function definition. A function body has a scope

nested inside the function’s definition.

Representing the if construct as:

if if-expression then if-statement else else-statement,

a variable declared in the if-statement is scoped to the end of the if-statement. A variable declared in the

else-statement is scoped to the end of the else-statement. This applies both when these statements are

simple statements and when they are compound statements. The if-expression does not allow new

variables to be declared, hence does not form a new scope.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 26

A variable declaration is visible immediately following the initializer if present, otherwise immediately

following the identifier:

E.g.

int x = 1;

{

int x = 2 /* 2nd x visible here */, y = x; // y is initialized to 2

}

E.g.

int x=1;

{

int x = 2, y = x; // y is initialized to '2'

int z = z; // error if z not previously defined.

}

{

int x = x; // x is initialized to '1'

}

A structure name declaration is visible at the end of the struct_specifier in which it was declared.

E.g.

struct S

{

int x;

int y;

};

{

S S = S(0,0); // 'S' is only visible as a struct and constructor

S; // 'S' is now visible only as a variable

}

A function declaration is visible at the end of the function prototype.

Note that the scoping rules for GLSL ES and C++ are not identical.

4.2.3 Redeclaring Variables

Within one compilation unit, a variable with the same name cannot be re-declared in the same scope.

However, a nested scope can override an outer scope’s declaration of a particular variable name.

Declarations in a nested scope provide separate storage from the storage associated with an overridden

name. There is no way to access the overridden name.

4.2.4 Shared Globals

Shared globals are variables that can be accessed by multiple compilation units. In GLSL ES the only

shared globals are uniforms. Varyings are not considered to be shared globals since they must pass

through the rasterization stage before they can be read by the fragment shader.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 27

Shared globals must have the same name, storage and precision qualifiers. They must have the same

equivalent type according to the following rules:

Shared global arrays must have the same precision, base type and size. Scalars must have exactly the

same type name and type definition. Structures must have the same name, sequence of type names, and

type definitions, and field names to be considered the same type. This rule applies recursively for nested

or embedded types.

4.2.5 Global Scope

Outside of all function definitions, there are two levels of scoping. Built-in functions are implicitly

defined in the outermost scope. The inner scope is known as the global scope. User defined functions

may only be defined within the global scope.

4.2.6 Name spaces and Hiding

Within each scope, there is a single name space. Declaring a variable adds a variable name to the name

space. Declaring a function adds a function name to the name space. Declaring a structure adds a

structure name and a constructor name to the name space.

All variable and structure declarations hide all declarations with the same name in outer scopes.

There is no mechanism for accessing hidden declarations.

Functions can only be declared within the global scope. Local function declarations (i.e. within a nested

scope) are disallowed. Functions (including built-in functions) may not be redefined. User defined

functions may overload built-in functions.

With the exception of uniform declarations, vertex and fragment shaders have separate name spaces.

Functions and global variables declared in a vertex shader cannot be referenced by a fragment shader and

vice versa. Uniforms have a single name space. Uniforms declared with the same name must have

matching types and precisions.

4.2.7 Redeclarations and Redefinitions Within the Same Scope

A declaration is considered to be a statement that adds a name or signature to the symbol table. A

definition is a statement that fully defines that name or signature. e.g.

int f(); // declaration;

int f() {return 0;} // declaration and definition

int x; // declaration and definition

int a[4]; // array declaration and definition

struct S {int x;}; // structure declaration and definition

A particular variable, structure or function declaration may occur at most once within a scope with the

exception that a single function prototype plus the corresponding function definition are allowed.

The determination of equivalence of two declarations depends on the type of declaration. For functions,

the whole function signature must be considered (see section 6.1). For variables (including arrays) and

structures only the names must match.

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 28

Within each scope, a name may be declared either as a variable declaration or as function declarations or

as a structure.

Examples of combinations that are allowed:

1.

void f(int) {...}

void f(float) {...} // function overloading allowed

2.

void f(int);

void f(int) {...} // single definition allowed

Examples of combinations that are disallowed:

1.

void f(int) {...}

void f(int) {...} // Error: repeated definition

2.

void f(int);

void f(int); // Error: repeated function prototype

3.

void f(int);

struct f {int x;}; // Error: type 'f' conflicts with function 'f'

4.

struct f {int x;};

int f; // Error: conflicts with the type 'f'

5.

int a[3];

int a[3]; // Error: repeated array definition

6.

int x;

int x; // Error: repeated variable definition

Version 1.00 Revision 17 (12 May, 2009)

4 Variables and Types 29

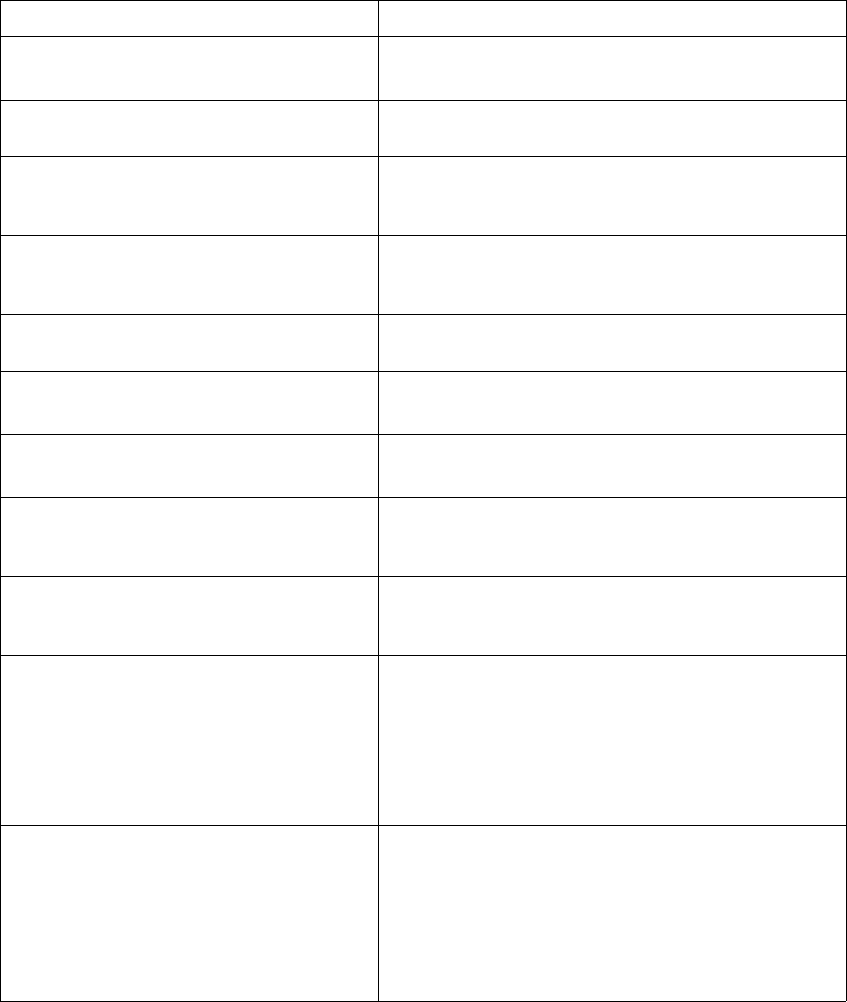

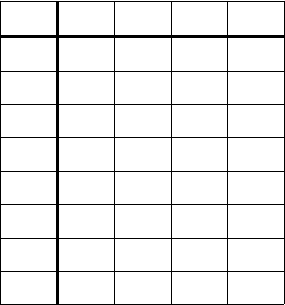

4.3 Storage Qualifiers

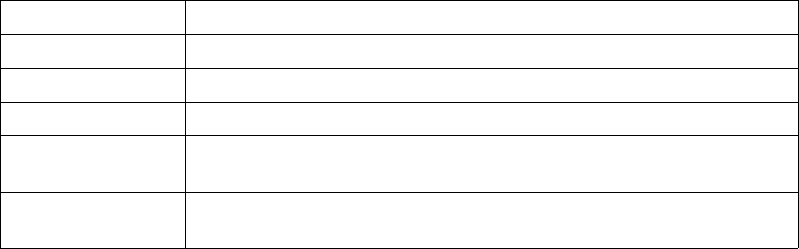

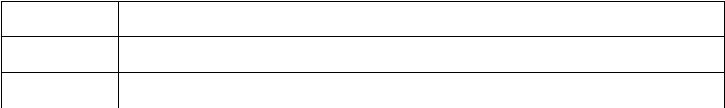

Variable declarations may have a storage qualifier, specified in front of the type. These are summarized

as

Qualifier Meaning

< none: default > local read/write memory, or an input parameter to a function

const

a compile-time constant, or a function parameter that is read-only

attribute

linkage between a vertex shader and OpenGL ES for per-vertex data

uniform

value does not change across the primitive being processed, uniforms

form the linkage between a shader, OpenGL ES, and the application

varying

linkage between a vertex shader and a fragment shader for interpolated

data

Local variables can only use the storage qualifier const.

Function parameters can only use const storage qualifier. Parameter qualifiers are discussed in more

detail in Section 6.1.1 “Function Calling Conventions” .

Function return types and structure fields do not use storage qualifiers.

Data types for communication from one run of a shader to its next run (to communicate between

fragments or between vertices) do not exist. This would prevent parallel execution of the same shader on

multiple vertices or fragments.

Declarations of globals without a storage qualifier, or with just the const qualifier, may include

initializers, in which case they will be initialized before the first line of main() is executed. Such

initializers must be a constant expression. Global variables without storage qualifiers that are not

initialized in their declaration or by the application will not be initialized by OpenGL ES, but rather will

enter main() with undefined values. Uniforms, attributes and varyings may not have initializers.

4.3.1 Default Storage Qualifier

If no qualifier is present on a global variable, then the variable has no linkage to the application or

compilation units running on other processors. For either global or local unqualified variables, the

declaration will appear to allocate memory associated with the processor it targets. This variable will

provide read/write access to this allocated memory.

4.3.2 Constant Qualifier

Named compile-time constants can be declared using the const qualifier. Any variables qualified as

constant are read-only variables for that compilation unit. Declaring variables as constant allows more

descriptive shaders than using hard-wired numerical constants. The const qualifier can be used with any

of the basic data types. It is an error to write to a const variable outside of its declaration, so they must be